You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more.

Embrace Life's Imperfect Journey

The talk weaves personal narratives, touching on themes of gratitude, patience, and the inevitability of suffering. It reflects on experiences with community support during crises, visits to monasteries in China, and television dramas linked to societal perceptions of justice. The prominent teaching emphasizes the Zen practice of letting experiences, including challenging emotions, "come home to your heart," rather than attempting to control and manipulate outcomes, referencing core concepts in Buddhist philosophy like the practice of patience (ksanti) as an antidote to anger.

Referenced Works and Teachings:

- "Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind" by Shunryu Suzuki: This foundational text promotes the idea of Zen practice as embracing experiences rather than manipulating them. It underscores the central theme of the talk about internal transformation over external control.

- Shantideva's "Bodhisattva's Way of Life": Referenced to highlight the view of anger as inherently afflictive, aligning with the discussion on how anger's sole aim is to cause suffering, framing patience and letting go as essential virtues.

- The Six Paramitas: Discussed in the context of Buddhist virtues, particularly emphasizing patience, and how these practices facilitate crossing from the shore of suffering to nirvana.

- Teachings of Suzuki Roshi and Kadagiri Roshi: Their insights on the practice of patience, letting things touch and move you, and living sincerely through accepting imperfection are key philosophical underpinnings of the talk.

- "A Hundred Years of Psychotherapy and the World Is Getting Worse" by James Hillman and Michael Ventura: Mentioned in the context of critiquing the therapeutic fixation on fixing problems rather than experiencing and being with one's pain.

- Yaku-san's Sayings: Reflects the futility of trying to control life’s outcomes, emphasizing a Zen approach of sincere engagement with reality as it is, likened to "planting flowers on a rock."

Cultural References:

- Mention of the O.J. Simpson trial and television's role in reflecting societal issues of justice.

- Reference to experiences in China and discussions with a monastery abbot about American disillusionment with material life and growing interest in Buddhism, indicating a cultural exchange and the spread of Buddhist insights.

AI Suggested Title: Embrace Life's Imperfect Journey

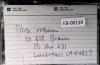

Side: A

Speaker: Ed Brown

Location: GGF

Possible Title: Sunday Dharma Talk

Additional text: Please return to Ed Brown, PO Box 631, Inverness CA 94937

@AI-Vision_v003

My house is about 50 yards from the fire. My neighbor's house, the fire came right up to his house. Thursday morning they were bombing his house with fire retardant and they had about 100 people or more fighting the fire at his house. Including there's convict crews. So it was quite an amazing outpouring of support and endeavor on the part of our government and many, many people which saved my house and other people's houses. Having been a member of the counterculture now for pretty much all of my life, this was kind of a nice turnaround. To have the government doing something with the tax money that I actually support. And people were there from all over California,

[01:04]

from Los Angeles County and San Diego and Amador and San Joaquin, coming to the rescue. It's pretty amazing. So when I agreed to give this talk, I didn't know that this was going to happen at all. In the meantime, so I had one talk already planned. On Tuesday I had dinner with some friends who had just come back from China and Tibet. So we talked about Buddhism in China and Tibet, which was interesting. We saw many pictures of people and places. They visited a monastery in China that is 800 years old and had a long talk with the abbot and told the abbot that in America,

[02:07]

some people at least are beginning to be disillusioned with material life and so they're quite interested in Buddhism. The abbot loved this. So he gave them special presents and everything. Please take these. So after dinner, Patty and I were watching Murder One. And of course that was the day of the O.J. verdict. The best line so far I've heard this week was there was just desserts or somebody in San Francisco was offering free O.J. with every six million dollar purchase. And just coincidentally, Murder One had several things that kind of related to

[03:14]

this fictionalized drama had several things. I mean, they had no idea when the verdict is coming out. And just coincidentally, it had several things relating to O.J.'s trial because in that particular episode, some of the assistant attorneys at the law firm got someone off who had squandered away the life savings of a lot of elderly people with his gambling compulsion. And the attorneys got him off and said that he was now reformed and he'd been going to 12-step meetings and he was willing to make restitution and pay it all back. So they got him off. So then he's confronted by one of the elderly people who's lost his savings and his wife had a heart attack when she found out that their savings were gone and died. So this elderly man confronts the defense attorneys and the defendant with a gun in the parking lot. And he says, you think you might have gotten them off, but you're a bunch of scum.

[04:20]

And he goes on and on and then he says, you know, I've spent my life developing my good name and I'm not going to waste it on you. And he puts his gun away and walks off. That was interesting. But the show got less interesting after the news bulletin came on that there was a fire in Inverness where my house is. Somehow television at that point didn't seem particularly relevant. And I called up a friend of mine, my next door neighbor, and asked him what was happening and he said that we had to evacuate within an hour. And it's an hour from where I was in the city to Inverness, so I wasn't sure whether to try to get there or not. I thought maybe they'll just tell me I can't go up to my house. So I decided to go anyway, finally. So while I was making the various phone calls and trying to decide what to do,

[05:30]

the other defense attorney, the head of the company, was saying, I heard him in the middle of my phone conversation saying, you know, so what if the guy gets off? Maybe he's going to get prostate cancer. He was trying to say that we human beings don't know what the punishment will be. And we don't necessarily have to assume that it's our responsibility for us to choose the punishment for somebody. That maybe just having to live their life and suffer what they end up suffering is enough. Anyway, I wasn't listening to it very closely, but I heard that part. So then I went out to Inverness and got a few things out of my house. That was interesting. And the people, the sheriffs, there were sheriffs and highway patrolmen and roadblocks, and we went through three roadblocks and people were very polite and let us get up to my house. And I had to walk in the last half mile.

[06:33]

Then I had to decide what I should save. That I could just carry out on my person. So at that point I decided that most of the things in my house weren't worth much. Someone here at Green Gulch yesterday said her house had burned in the Berkeley fire and she said, I don't miss those things at all. I felt liberated. The hard part was having to go out and buy another toothbrush and then everything you need just for your life, you have to go out and buy it. And then staying with friends. She said some friends invited them to dinner one night whenever they wanted to come. It was really sweet. But she didn't miss the things in her house. She missed just having a place to be. So I got two Buddhist statues and my okesa,

[07:36]

my formal robe here, and a few odds and ends. I had a little cash, so I got the cash. And so then this week has been waiting to see what would happen. And as long as I could call my house and get the answering machine, I felt pretty reassured. Several people who called up to ask if we were okay said, well I guess we've got an answering machine, you must be all right. And then on Thursday though, I called my house and there was no answer. And my neighbor's house was busy. And the first time it was busy, I figured, well it's going to be busy all day. And it was busy all day, his phone. And my phone just rang and rang all day and the machine never would answer. So at that point, I figured, I decided, this is an interesting exercise, so to speak, do you project or imagine what must have happened?

[08:41]

Or do you wait to find out what actually happened before you get too involved in your reaction? And I tend to fantasize the worst, and dramatize that and then start reacting to that. Who knows what's happened? Are the phone lines down? Did they just sort of turn off the electricity while they're fighting the fire? There's no way of knowing. So then, by Thursday afternoon, somebody called me up and said that from the ridge on the other side of Tomales Bay, he could look through his binoculars and see my neighbor's house and people on the porch. So he said, it must be okay. So they just bulldozed part of the yard, is all that happened. And removed a lot of the trees around to make a fire break. But coincidentally, this week, I'm thinking about patience.

[09:46]

This was a matter of patience. And waiting. And not knowing what would happen. And so I was recalling Suzuki Roshi's teaching that most of the time, we have a tendency to try to control or manipulate people and things so that they behave according to our wishes. And give us good experiences rather than painful ones. So we try to control and manipulate. And he said, practicing Buddhism is to practice letting things come home to your heart. Letting things come home to your heart and touch you. To touch and be touched by the things of this world, the joys and sorrows, the pleasures and pains.

[10:51]

Buddhism is not intended to be some better way to control and manipulate people and things. Like, you know, I could love them into behaving right or... If I'm really patient with them, they'll change their ways. Yes. And many things, of course, are difficult to allow to come home to your heart. Like the fact that maybe your house is going to burn down or has burned down. Coincidentally, because I was staying in Fairfax with some friends while this was going on, since the flat we rent in San Francisco, the landlord was repainting the outside

[11:55]

and they were ripping off the old stucco because of the earthquake damage. So it was really noisy at our flat in San Francisco. And so I decided to stay in Fairfax with some friends. And because I was in Fairfax, then I went to see a very good friend of mine. Harriet, whose son is 38 and is in a wheelchair and has ALS. ALS is Lou Gehrig's disease and it affects, I guess, whether the nerves... After a while, the nerves can no longer activate the muscles, so it's a progressive disease causing paralysis. So now he can no longer talk because the muscles involved in talking don't work. And so they've all learned Morse code. So he can move his lips in dots and dashes to try to communicate something. Because at some point, people in that situation are in what is known as lock-in.

[12:59]

They become shut in and then they have no way to express themselves to the world and it's very isolating and sad, painful. And then it's sad and painful for the mother and for the friends. And earlier this year, in January, Harriet moved her son into her house because he had been living actually near here. And he began coming here sometimes and he was in the Mere Beach Volunteer Fire Crew. He's a very husky and athletic person. So in January, she moved him into her house and has been taking care of him and she became exhausted with the effort, as you might expect.

[14:00]

And so they considered putting him in a convalescent hospital and they went to visit one and while he was there, the tears started rolling down his face. And so she decided they couldn't do that and what she did instead is an alternative. It's interesting, it's rather like the fire. She mobilized his friends and her friends to come and help her take care of him. And she's made up a schedule and people come one night a week or are available to substitute and to help take care of him and so that he can stay at home. And so now she's found that there was a tremendous outpouring of support for her when she asked for help in taking care of him. So this weekend, it's interesting that these two events

[15:05]

that are both in their way so painful and difficult resulted in an outpouring of support and help from other people. Sometimes complete strangers. So it's been rather, for me, rather heartwarming because we hear so much these days, of course, about crime and various human deficiencies. So this has been quite wonderful to see. Thank you. So along with the, you know, in letting things come home to your heart, actually there's the possibility of a response.

[16:09]

A response which is not just anger or discouragement or giving up but some real response that mobilizes people, that mobilizes you and mobilizes others. Anyway, today I'd like to talk more about patience because the advice of Suzuki Roshi is to know that Buddhism is to practice letting things come home to your heart. It's not just good advice. It's not possible to control and manipulate people and things so that they behave according to your wishes. And often when things don't behave according to our wishes then we have some tendency to become angry as though that would help and as though that might encourage things to behave more according to our wishes. So patience is considered to be one of the main antidotes to anger.

[17:13]

And it's the third in this list you may be familiar with of the paramitas. There are six virtues that are known as paramitas. The paramitas are, the usual translation of paramita is perfection. It's a perfection. They're considered perfections in the sense that they help one cross from this shore to the other shore, from the shore of suffering to the shore of nirvana. So literally the practices are intended to be what brings you peace and calm and harmony in your life rather than continuing to be in a battle with what happens. Paramita is also intended as a perfection because there's not a separation between the doer, the action and the object of the action. And one is not keeping track of how patient I've been and how I'm getting to be more patient. Or I'm getting now I'm less patient

[18:20]

and congratulations to me and so on as I get better at this. We're all in this big soup together called human life. And we affect one another. Anyway, the first is generosity and then the second is practice of precepts and the third is patience. And then the fourth is in vigor or endeavor and the fifth is concentration. The sixth is wisdom. And patience is not intended to be just something that you force yourself to do. And in that sense, I was thinking of Kadagiri Roshi used to say sometimes, you know, Zen practice is not like training your dog. And you say, sit, heal, fetch.

[19:22]

So you don't just tell yourself, be patient. Don't be angry. How well does that work, you know? Usually if somebody tells me when I'm angry you know, to be patient. It's not usually very effective. It has the opposite result. Don't tell me how to behave. And if I try to tell myself like that, you know, it doesn't work very well. So patience is not, you know, something you can just force yourself to do and force yourself to be patient. The idea of, you know, practicing patience really has a lot to do with insight. Insight is associated with the six paramita wisdom. But in particular, the insights,

[20:24]

there are a few insights with patience that I will mention today. The first is sometimes considered to be insight into the, well, it's, you know, in some way, the insight into the first noble truth in Buddhism, the inevitability of suffering. You have a human body. That means it can get sick. And you can have ALS. And things can happen to your body. And things can happen to your mind. And things can happen to your friends. And things can happen to your possessions, your house. Nothing is safe. Everything is changing and life is uncertain. So how would you, you know, expect, you know, that things will behave and be there for you in the way you want them to be there for you and get angry if you're not, you know, when that doesn't happen?

[21:25]

And how appropriate is it? The idea of anger in that situation is somebody is, you know, somebody, the universe is doing these things to you. But Buddhism points out that things arise and disappear by cause and condition. And the universe is not, you know, picking you out. Sinking you out because you have a human body. You know, you have a human body. You've been born a human being. Then this is the nature of human life. It's uncertain. And the anger in that sense is said to make intolerable situations even more intolerable. Whether they're insect bites or beatings, it's said that when you become angry, those afflictions are even more intolerable now. . So this first insight, inevitability of suffering,

[22:33]

and the second insight is to notice how things that are painful and difficult and suffering encourage you to practice, encourage you to renounce things, and to renounce our narrow vision of what we have our hearts set on. And the way it has to be or we'll be angry. Our renunciation in this sense is associated with or the same as bodhicitta, the thought of enlightenment, this spontaneous and continuous wish to be free from anything that might disturb you or anything that might lead to your dissatisfaction. This spontaneous and continuing wish to be free. So this is, you know, different than what is so popular these days, the victim mentality. If something goes wrong, whose fault is it?

[23:35]

Who can I blame? Who can I sue? Who can I, you know, put in prison? Who can I beat? Who can I hit? Who can I kill? Who's the cause? And so this insight is also then related to the fact that the cause of anger must not be any of those things outside, considering that suffering is inevitable and considering that, anyway, there's also this noticing that the cause of anger is my wish for things to turn out the way I want them to and my failure to renounce that wish when things don't turn out that way. Then there's anger. So this is another insight. And a third insight is the insight into, you know, that phenomena and you yourself and other people are selfless without self. So I'll tell you a story about this.

[24:36]

This happened to me several years ago, but it continues to happen to me pretty much daily, this sort of event. This morning when I was leaving my house to come here, my robe, my little jacket, Zen jacket, black Zen jacket, has little twist ties. Tie it on this side and then you tie it on this side. And then the one on this side, I realized, was hanging by a thread. So I thought, I'd better get out a needle and thread. So then I got out the needle and thread, but the container, that little tin container that all that is in, that I keep there, fell open and spilled all over the floor. Why did it do that? I mean, I'm trying to be helpful. I'm trying to mend something. Doesn't it understand that? Why should it punish me like that when I'm just trying to mend my jacket? And I've had a hard week. Besides, you know, my house almost burned down. So I don't, you know, I don't think very clearly sometimes,

[25:45]

you know, with these kind of insights that I've been telling you. But you can see in a simple example like this how inevitable that it is that things like that happen and those things didn't set out and conspire, you know, to make me angry. Why don't we just fall open and then we'll see what happens to him. Laughter And it's pointed out, you know, that people aren't any different than those things. People, if they do something to you, they don't, they're under the influence and they're being driven by their compulsions, by their anger. And so if they do something, it's not as though they really set out under their own volition and by their own self-will to do that to you. They're being, they're compelled and compulsed into doing something to you.

[26:49]

So who do you get angry at? If you get angry at them, they're in the position of having, you know, of being helpless with their afflictions, with their afflictive emotions. So you could, so then do you get mad at the afflictive emotions? Anyway, there's no end to it. But very similar to this, a few years ago, I, one morning I went to have breakfast and I got, I went to get an egg out of the refrigerator and it stuck to a little cubbyhole on the door. Usually at breakfast time, one is in a little bit of a hurry. Laughter Because you have things to do that day and you have, you want to get somewhere and accomplish something and be a good person. Laughter Make some money, take, pay the bills, not be a deadbeat, you know, all those things. Maybe you do really good work, you know,

[27:51]

fighting fires or, you know, being with cancer patients and so on. I don't know, but I don't do very important work. I'm just in a hurry anyway. Laughter You know, I think if I go faster, maybe I'll get to that important work someday. I don't know. But the egg is sticking and I'm in a hurry and so I think I better be careful or if I pry too hard on this, it's going to break. So I wiggled it just a little bit and nothing happened. So then I tried a little harder and it cracked. And then it started drooling down. It's all those jars in the door of the refrigerator that you've never, you haven't, you know, you know they're good. It's like all that stuff in your house. You probably are never going to use it. You never miss it when it's gone. But you kind of feel like maybe

[28:51]

you shouldn't let the egg drip all over it anyway. Laughter So then I was, I was already mad and I thought, now what do I do? Because should I go in the other room and get the sponge? Because the refrigerator is a little alcove, you know, pantry off the kitchen. Should I go get the sponge or should I just stand here and try to catch it with my hands? So I decided to stay there. And then I wiped up, I cleaned up the mess. I was really kind of, I was really mad at that egg, you know. And I thought, you know, why couldn't you just let go? What's wrong with you? Why don't you just let go? And this is a perfect example of how, you know, it can only make you mad if you attribute, you know, this self to these things.

[29:51]

And that you have a self. Because then the refrigerator door and the egg get together and they say, he's really, he's really in the mood today. You can see it. You can sense it even across the kitchen. So when he comes and opens the door and he wants an egg, you hold on to me, I'll hold on to you. Then when he tries to wiggle you loose, you'll break, and then we'll see what kind of a fit that gives him. Now, when things conspire like that, you have a reason to be mad at them. You know, if this is all just impersonal cause and effect and conditions, what are you going to get mad about? So you kind of have to assume that these are frustrated, like frustrated bureaucrats or people who have no power or competence in their life and this is the only thing that they can do to manifest themselves in the world.

[30:53]

Like they can't, they're not any more creative than that, et cetera. And so this is the way they act out their frustrations with being who they are and stuff and whatever. So I get really mad and then of course, who needs to let go? So we like to give this advice to the things out there which is, you know, probably better intended for let go as a kind of like, what did we just call that? Renunciation? And then, so then I got out some other eggs that were more cooperative. We have another saying for this these days, of course, you know, things happen and we say, I don't need this. I just don't need this to be happening now. So then I got out some cheese

[31:54]

and I went to open the cheese and now because of all the problems with tampering and stuff, you know, you can't open up a cheese package anymore by hand. It's impossible. So I'm trying to get this thing open and then I get out a knife that's so dull that nothing happens. And I'm saying to the cheese package, open up. Open up. And it's again, it's like, who needs to open up? And do you think the cheese manufacturers and the cheese packages and the plastic are all conspiring to do this to you? It's just stuff. You know, it's just to the world we live in and behaving by, you know, the laws of the universe. Sometimes I put my coffee down on the counter and it's on top of the newspaper and then I put it down and I let go and the next thing it's like falls over. And then I get really mad,

[32:57]

like, why couldn't you just stay there? I put you there and it turns out that underneath the newspaper there was a pen or a pencil, you know, and so it was just tipped enough so that, you know, and then it would fall over and spill. And then, you know, the computer's right nearby and, uh-oh. So this is all about control and manipulation of things. And this is not about, you know, letting things come home to your heart. And if you want to open up, to open up is let things come home to your heart. Let things do what they do. Let things misbehave. And then you practice letting go and you practice opening up So this is patience. So patience is not, you know, a particular kind of practice.

[33:57]

It's actually a kind of insight. It's many insights that give us patience. So I also think of a saying by the Zen master, Yaku-san, and today I'm thinking about it in the context of patience, but he said at one point, whatever you say, whatever you do, it's of no avail. That doesn't sound very positive, does it? But, you know, much of our life is in that category. Whatever you say, whatever you do, it's of no avail. It's not going to stop the forest fire. It's not going to change the ALS. It won't give you another human body. You'll still have your quirks

[34:59]

and your impatience and your anger. And you can't get, whatever you say, whatever you do, you won't be able to get things to accord with your wishes to anything. You know, once in a while, you have maybe, once in a while, it's like, you know, the gambling in Las Vegas. Once in a while, you have one of those successes that keeps you addicted to the process of trying to manipulate and control all the phenomena to your liking. But anyway, Yaku-san's disciple said, yes, and not to say and not to do, that's also of no avail. Isn't that good? So don't think that just because saying and doing is of no avail, that you should sit around and not say and not do. So what will you do? So I like Suzuki Roshi's advice,

[36:00]

you let things come home to your heart. And you touch things and are touched by things and respond to your life and the things in your life and the people. And this is outside of, you know, any particular rule or strategy or, you know, right or wrong thing to do, but, you know, letting things touch you and responding to things. And remembering your thought of enlightenment, to not be disturbed, the spontaneous and continuous wish to be completely free and undisturbed by things that are dissatisfying and potentially upsetting. Let that come home to your heart too. And Yaku-san said,

[37:04]

this is like planting flowers on a rock. Our human life, you know, we go ahead and do things and it's planting flowers on a rock. So does that mean you should not do anything? No, you go ahead and plant flowers on rocks. We all go ahead and build houses, even though they may burn down, even though, you know, they'll get old. We take care of our life even though it's going to disappear. It's all very ephemeral like flowers on a rock. Whether the flowers are on the rock or not, they're ephemeral. And Yaku-san's disciple, I think it was, you know, Ungan, said, yes, you can't even insert a needle. In all of this, you know, there's no way to penetrate or, you know, have any leverage in the situation. Things of our life happen.

[38:08]

In that sense, you know, this is also described that things in our life happen inconceivably, beyond our conception, beyond our idea, beyond our wish. Things arise and disappear beyond, outside of that whole realm of our wishing and striving. The universe is appearing and disappearing in a rather, in that sense, inconceivable fashion. And there's no way to get any little, even a pin in there, let alone some effective kind of leverage. But one of the, you know, one of the liberating aspects of this kind of understanding is that

[39:09]

this means you can go ahead and be yourself and be sincere and true to yourself. Sincere means to be without wax. The S-I-N is like sans in French, without, and the serre is wax. Wax was used to fill in the chips of metal coins so that they weigh a little bit more when they're weighed. Wax is used in sculptures too. You fill in the cracks and crevices and the rough edges. You make it all smooth and perfect. So someone who's sincere has, you know, the cracks, the scars of being a human being. You have the scars and the word character is, you know, means lined. Character is the lines you have, the lines of your life and the experience of your life lines you. It's interesting to me,

[40:12]

I noticed in a Japanese restaurant several years ago, you look at the plastic dishes and they don't have character because they don't age very well. They don't develop lines. So to be sincere is to, you know, have your lines and to have your, you know, character and to have your blemishes and your faults and your cracks and your chips and allow them to be there and you don't have to try to be perfect. You don't have to say or try to say or do just the right thing. You don't have to try not to say, not to do, you know, because maybe that's better. You can just, you can let things come home to your heart and you can respond to things and you can touch and know yourself very deeply and intimately. So in this sense also, of course, enlightenment is sometimes known as attaining intimacy. Letting things come home

[41:17]

to your heart is to attain intimacy. It's attaining intimacy with the joys and the sorrows, the pains and the pleasures of, you know, human life and not thinking that you would emerge unscathed and unlined or there was some way for you to attain immunity and if you couldn't be immune, you know, you have a right to be angry and blame someone or find someone at fault or find things that, you know, or the universe. Attaining intimacy is also attaining, you know, knowing things then and knowing these, having these kind of insights, this is intimacy. We all have this capacity to enter into the depths of our life and enter into the depth of our experience and know things through and through to touch things

[42:18]

and be touched by the things of the world and the things of our life. So I have one more short story for you. A monk once asked the master, what about the people who leave the monastery and never return? And the master said, they're ungrateful asses. And the monk said, what about those who leave and then come back? And he said, they remember the benefits. The monk was curious as you might be. What are the benefits? And the teacher said,

[43:23]

heat in the summer and cold in the winter. So to have that kind of experience and to know heat and cold as benefits, to not be impatient with heat or cold, but to allow heat and cold to touch us and come home to our heart, then we know there are benefits. Patience and tolerance of things in this way gives us some sense of the preciousness of things and the benefit of things as well. This isn't just about enduring something painful, but how to find how you can have benefit in your life, to be moved by things. Okay, so

[44:37]

thank you very much for all of your sincere efforts to enter into the depth of your being and the depth of our life with all beings, with the whole universe of beings. Okay, my thinking, you know, like most people's, isn't very accurate. It just kind of makes things up. How is that? Huh? How is that? How is that? Yeah. It happens in a rather inconceivable kind of way. So you can't really say that you can't really conceive of it. Conceive of the way that my thinking goes? The way my thinking goes? No, I can't. Whatever I say

[45:40]

is obviously priceless or, you know, valuable or important in some way. Yes? Did somebody say Ed? Oh. Well, if you have any thoughts or questions or comments that you'd like to make, you're welcome to. I may or may not respond yet. Well, I think, I mean, isn't it obvious that everybody else in the world is able to do that? Or it looks like other people are doing pretty well at being a human being. You know, everybody but me. I just as soon like be like them, but, you know, I, I, I, you know,

[46:41]

when I look carefully it turns out that other people are also struggling and having the difficulties. I mentioned yesterday I had my one day retreat here and Kurt Vonnegut said in one of his books, the thing that we're really reluctant to admit to one another is just how painful and difficult it is. So we go along trying to like, no, this isn't painful or difficult and like, no, I don't have a problem and everything is just fine. And then when you admit to any of that then people say, you know, uh-oh, what's wrong with you? And then you're sort of like, you better keep your distance from anybody like that, you know. But it's also curious that in, in our effort to be perfect, you know, to present to the world a competent, capable, loving, kind, interactive kind of person. Yeah. All right.

[47:42]

Paramitas. The first is generosity. That's, you know, giving, giving material, food, shelter, clothing, giving your time and effort and it's, in a fundamental way, it's giving your attention to something. It's a, it's an act of generosity to be aware of anything. To allow your, you know, to give your awareness to something. So, it's the opposite of, it's the same thing as what we usually say is pay attention. But actually we should, we could be saying give attention. So, generosity. And the second is the practice of precepts. Third is patience. Then fourth is vigor. Fifth is concentration. And sixth is wisdom or insight. Yes, in the back? Oh, okay.

[48:49]

Oh, yeah, okay. About being perfect. And then, so we present, we try to present this self-image that we, that we think of as a good person or the kind of person I'd like to be and we try to present that to the world and get people to agree that that's who we are. And usually they've noticed a long time ago that's not who we are. And the only person that's a surprise to is me. So, after a while, you know, so when, and so what that has to do with is often this sort of filling in, you know, putting wax in and then presenting the image instead of having cracks and blemishes and defects, that's all covered over. It's a little bit like makeup, you know, but it's how we make up ourselves as a person as opposed to just our face. And then we try to present that. So then when somebody sees through that and we're exposed, you know,

[49:52]

so then that can be very upsetting. That's often the source of our anger is because we find out we're not the person that we were trying to convey to the world that we were or that we'd like to be. So then there's often anger there. um, so being sincere, you know, or it's also then that has to do, so sincere is being the person that you actually are, having the problems you actually have. And then that also means, for me, it certainly means that you learn to love somebody who's less than perfect or have compassion for somebody who's less than perfect. You know, we think, well, I could love somebody who was perfect, so I better sit out and try to be perfect. So it's, it's what, you know, Robert Bly and others have pointed out is lowering your standards and seeing if you could love somebody who's less than perfect or have compassion for somebody who's not, you know, the most wonderful being. I noticed this

[50:54]

when, when I first started cooking, which was in the 60s and then, and then I, it was really important to me that the food was good and then I, and I started thinking about it after a while, why is it so important? And then I thought, well, if people, and when I thought about it, I thought, well, if people like my cooking, then, then that must mean that they would like me. And then, well, what's so important about whether they like me? Well, maybe they could convince, they could like me enough that they convinced me to like myself. And then it's at that point I realized, uh-oh, I guess, I guess I don't like myself and I need some evidence in order to like myself. So, um, certainly an aspect of Buddhism is finding out how to have compassion, finding some compassion for somebody like that, having compassion or love for somebody who, uh, you know, without any evidence,

[51:55]

really. This is the, Bodhisattva's way is to have, um, compassion or love without any evidence of that they're, that they deserve that. You know, it's like, what have you done lately? So if you think you have to be a good cook in order to have people like you in order to like yourself, then that's pretty flimsy self-esteem that's subject to the ups and downs of the things of this world that happen. So what about a more, um, you know, unconditional kind of compassion or love for yourself and for other beings who are struggling as each of us is struggling? And to acknowledge the way, so acknowledging your own less-than-perfectness or in somebody else's less-than-perfectness actually allows some compassion to, you know, then there can be compassion in the situation instead of trying to get everybody to become perfect. Does this make sense? And, um,

[52:57]

so that's some, that's some ongoing kind of work or effort in our, in our part, you know. But it's very much, and so much of practice is, um, uh, well, anyway, I think of Thich Nhat Hanh and his practice of smiling. He suggests that people practice smiling. And then many people say, well, suppose I don't feel like smiling. Well, can you smile at someone who doesn't feel like smiling? You know, this is not meant to be an exclusive kind of practice. Why don't you see if you can give somebody who doesn't feel like smiling a slight smile? Or somebody who's angry a slight smile. So that's a, literally a way to cultivate compassion for yourself and for others who don't feel like smiling. You have compassion or some, give that person a slight smile. So you have to start somewhere with, uh, your compassion like that. Yes, in the back. Um,

[53:59]

when I drop the, uh, W or that man is a figurehead. I know it's not the figurehead he's done it. I blame myself for being close to him. I blame you. I blame you. Laughter. Oh, I never blame myself. See, I always put the blame on, on that, those things. Laughter. Those things. I'm a good person. I'm a spiritual person. Laughter. Laughter. Uh-huh. Yeah. Yeah. Right. No, not much. No, no. No, it's about the same thing. When I used to watch Suzuki Rishi with, you know, working with rocks,

[55:06]

I had worked in the kitchen at Tassajara for two and a half or three years. And then I went out and for several weeks I was digging in the garden at Tassajara. And I would we were taking the dirt, the rocks out of the dirt. So after I'd been all that time in the kitchen, you just, you shovel into the ground and then you toss the dirt against the screen that's set up at an angle on the rocks. The dirt falls through and the rocks stay on the screen. And then you put the screen, the rocks in a wheelbarrow and wheeled them off. So I just did that all day long for a while. And then at some point we started working on stone walls. And then later on Suzuki Rishi decided, you know, invited me and other people. Mel worked, you know, Mel and I worked together with him for a while and some other people. But I noticed when he worked with rocks, if something didn't fit, he just tried something else. And if it was me, it's sort of like, that didn't fit. And whether, you know, whether you blame the rock for not fitting

[56:15]

or yourself for like, why didn't I see that that wouldn't fit? That's all sort of extra at some point. And he just like, well, if it doesn't fit, well, I mean, it's not, you know, if it doesn't fit, then you sometimes you can chisel off the rough, you know, the place that doesn't fit and you can make it fit. But at some point, well, let's do something else. And you go on to the next thing. Because, I don't know, it's just like spilled milk. And it doesn't matter whether, you know, what the, you know, those things or me or what it is. You just do the next thing. And then you, otherwise you can sit there and, and what did you think? Because we tend to keep going over and over those things as though we could become perfect. As though we could do things and never have a problem. If I paid more attention, then everything would work and I'd never be frustrated like this. And it's a delusion. That's the, that's not recognizing the inevitability of suffering. No matter how hard you're going to try, you'll have some suffering and pain.

[57:19]

No matter how careful you are. And things will misbehave. And, and whether, you know, I, I, I don't, we don't know for sure, but I tend to feel like O.J. is guilty, actually, you know, or, or not innocent. He's not guilty, but that doesn't mean he's innocent. Or whatever it is, you know, but there's somebody or somebody in that sort of situation will tend to feel like, you know, something, someone, something won't behave right. So finally you have to, you know, get rid of it. So that's a lack of, no, not noticing the inevitability of how things don't behave the way you'd like them to. Which is another way of saying what, what suffering is in Buddhism. Things are not behaving the way I'd like them to. Smash them. When my computer doesn't behave the way I, you know, would like it to, then I,

[58:24]

so like I'm tempted sometimes to smash it, but I understand that that's not going to really solve anything and will in fact create additional problems for me. This is the second precept, you know. The second paramita, which is the precepts. Don't cause yourself any more problems than you already have. Yes. Yes. Yes.

[59:38]

Yes. [...] Well, when, when anything arises, and anger seems to be, you know, one of the pivotal examples of this, but when something arises, we have several options. And what Buddhism says is that mind itself is not, is, is and always will be completely free and liberated. So when you become angry, you are not anger. Anger is not you. Mind is not angry. Anger is not the mind. And, but when you become angry, we forget that and then we feel like I'm tarnished. I'm, I'm, I'm pained by this.

[60:42]

And this is one of the afflictions of anger is that we forget the already emancipated nature of mind. And we feel, we feel dirty and discolored or stained by the anger. And the various options we have. One is to, you know, we identify with the anger and we can feel, you know, righteous about it. And one is to disidentify with anger. No, that's not me. It's angry. And try not to have anything to do with it and try to keep our distance from it. But in that sense, it does help to, and as you say, whether it's somebody being angry at you or you being angry, it's anger is afflictive. Anger is painful. That's one of the things that Buddhism points out. That anger, well, I've been reading, re-reading the Bodhisattva's Way of Life by Shantideva,

[61:50]

which is from the 7th or 8th century. And he says the anger's sole aim is to afflict you. You might think that this anger is good for something else. Like, you know, if I get mad at that person, they'll never treat me like that again. And so on. But it's not good for anything else. It's only good to make you feel awful. But it helps me anyway to notice how, you know, that mind can take all these different shapes, but that's not inherently mine. That's not the nature of mind. And that is not really me, finally. So it's a way for me to let go of it at some point. And that's one of, of course, the basic practices in Buddhism,

[62:55]

is to notice how the phenomena that is appearing and disappearing is not you. And that's sometimes called detachment. But it's to not identify with the various experiences happening, as being me or reflective of my worth or value. You know, if I get angry, I'm a bad person. If I'm kind, I'm a good person. So I feel good about myself, I feel bad about myself. Neither of those is particularly, you know, is fundamentally you yourself. You yourself are without any characteristic. So in that sense, you don't have to feel quite the same compulsion to get rid of something that's distasteful, or to acquire something that's pleasant. Because at best it will only be temporary anyway.

[63:58]

That you get something or lose something, or that you get something or get rid of something. Did you have your hand up? A moment ago. If you are without characteristics, then what are you? Well, if you're without characteristics, then who are you? Or what? Or what? Well, one of the classic answers to that is, I don't know. But we like, you know, we keep liking to be able to identify something as me. But as soon as you identify it, then that's not you. As soon as you identify something, then that's you as an object. Even if you say, I'm angry, that's you as an object. Who's saying I'm angry? Well, then if you say something about that, that's another object.

[65:04]

So sometimes people say, well, there's this part of me that gets angry, and then there's this other part of me that seems to be really patient. And then sometimes the part of, you know, and then who's doing the talking? Who's telling the story? There's always somebody who's the subject. The subject is not the object in this case. The subject has no characteristic. As soon as there's a characteristic, you've objectified yourself. And then if you try to do something about or fix up or, you know, improve this objective self, it's an endlessly frustrating thing, because you always end up with a self that, you know, some people like, some people don't like. You like it sometimes, you don't like it sometimes. And it's a kind of charade. So, you know, sometimes you have fame and sometimes blame and various things. It's inevitable. Yeah, that's what I feel about a lot of therapy.

[66:12]

Big problem, from my point of view. I've tried out various therapeutic situations over the years, and that's one of the things that frustrates me about therapy, is that a therapist seems to want to fix me. And I have more the feeling like Rilke, don't get rid of my demons, they're my angels too. I don't want to be fixed. I want to know how to tolerate, you know, what isn't fixable. I want to know how to live with what isn't fixable. I don't want to fix it. And I was just, in fact, sharing with people at my retreat yesterday, I read them a part of the passage from the book A Hundred Years of Psychotherapy and the World is Getting Worse. I mean, it's been 2,500 years of Buddhism and the world has been getting worse too. So, it's obviously a flip kind of a title. But it's by James Hillman and Michael Ventura. James Hillman is, of course, a well-known Jungian therapist, and Michael Ventura is, I don't know how to describe him.

[67:18]

You know, he's written these books about shadow dance in the USA, where he traces the roots of rock and roll music back to Africa, and various things, and fascinating material, and voodoo, and all this has gotten into rock and roll. It's pretty amazing. Anyway, he's quite an interesting person, but they wrote this book together, parts of which are kind of a conversation or dialogue. And that's one of the points that they make, is that when therapy preoccupies itself with just fixing things, then you have all this psychic material, which is like anger. Then if you think, well, I need to process this, and they say like cheese, so you could have a lot of neat little yellow slices and a nice little package, then you're trying to be perfect. You're trying to end up with this beautiful image, and you've processed all this painful stuff, which otherwise is your ore. The stuff of your psyche, which is this fecund, dark, deep stuff that is your real resource, ore.

[68:19]

And if you just process that away, then what are you going to work with? What is going to move you through your life? So they are suggesting not processing it, but it's more like Buddhism, which is you just live with it. Or in our case, literally sit with it. It's not like when you sit with things, you're supposed to be able to get rid of them. No, you just hang out there and sit with them. Hanging out there and sitting with them is called also patience today. I have a certain personal take on therapy, and they're not trying to say, James Hillman and Michael Ventura are not trying to say that all therapy is useless because of it. They're just trying to say, as they do in that particular passage where they're talking about all this, James Hillman finally says,

[69:20]

well I'm not trying to say therapy doesn't work, I'm trying to say if you go to a therapist, be careful about the collusion between the therapist and the part of you that doesn't want to experience your pain. And this wants things to be fixed. What do I take for this? What do you call it? What's the diagnosis? How do I get cured? How do I fix this? How do I get over this? What should I do? What's the recipe? What's the remedy? And what about actually experiencing your pain? And some therapy does that. So what they're saying is be careful about when you go to therapy about that kind of collusion between the fix-it therapist, the possibility of the fix-it therapist colluding with the part of you that doesn't want to experience your pain and just wants to find out how to get rid of it and either process it or fix it or what medication can I take and how do I not have to deal with all of this? How do I not have to have this around? You know, parts of our psyche are like the crank uncle or whoever. I mean, parts of our psyche, I often have said over the years,

[70:26]

I mean, I don't like having to be me, but nobody else seems to be doing it and I don't really seem to have much choice about it. Because lots of me is not a very pleasant, nice person and all that Buddhist practice is not somehow like, okay, well you don't have to be that kind of person anymore. I don't know, it seems endless to me. All the muck. Yes. So you're saying that in your practice and the movement that you've picked through the years, you're still going through the same pain situation that the rest of us go through and hope in the future? Exactly. I don't know, I think I'm a little more tolerant or patient

[71:37]

with things than I used to be. Who knows? Any description you make like that is just a tentative, once you objectify yourself, as I was just saying, that's an objectification of who I am or what I am like. So there's one side where you say, well, I'm like this, I used to be like that, and on the other hand, right from the start, I'm completely free. I am already emancipated. My mind never was, mind itself never was angry. Even when anger appears, mind is not angry. Anger is what's angry. So right from the start I also have liberation or there's me who is, I don't know who that is, and so right from the start there's me not knowing who that is and inconceivable me. And so, from that point of view,

[72:42]

we'll never finish the task of perfecting ourself in some kind of objective terms. I'm so much less angry, I have so much more wisdom, I have this, I don't have that, congratulations, oh boy, I'm in such a better position than I was. No, all along, and it's one of my favorite expressions of sadhikirishi, the problems you are now experiencing will continue. For the rest of your life. Don't you think so? I mean, you're still going to have eyes and ears and a nose and you'll have thoughts and emotions and feelings and stuff happens. And the world inflicts itself upon you, whether you want it to or not. Yeah, and then there's your reaction to it. And so, you can find out, you can practice and learn how to react somewhat differently. But then that doesn't mean that from then on you will always react in this new improved manner.

[73:43]

Each moment is somehow a new moment and there's no guarantee that, from my point of view, there's no guarantee that you will, you know, in that sense, there's, you know, the understanding that practice is not in order to get enlightened. We practice sitting because we are enlightened, because we have some recognition of all of this striving and struggle to get someplace in your life hasn't worked, so why don't I just sit down and sit still and be with things in a simple and direct way. And then maybe you have some realization or awakening, and then you practice some more. So even after enlightenment, there's practice. There's practicing with the moment now. And none of us know what to do, you know, or how to be. And there's no recipe that you can follow. You know, and no, this is just exactly the right thing to do in this situation. I sit up here and then you ask things and then I say something. And maybe some of you get something out of it and like it

[74:50]

and then others of you sit there and like, what is he talking about? And like, does he have to be so flip or whatever? I don't know, you know, I end up, you know, at some point I hear various things about what people think about what I say and like, so how are you going to, what are you going to do? I don't know. So I figure like, well, I'll be sincere and I'll say what I have to say and then you can either use it or not or set it aside or throw it back at me. We'll go on from there. I personally find that there's a tremendous comfort or reassurance in the sense that the problems you are now experiencing will continue forever. And it's the fundamental, you know, first food is truth, but there's a reassurance in that, which is, and the reassurance is so you don't have to keep struggling to eliminate all of that and to not have it in your life. And you can allow it to be there and you don't have to criticize yourself,

[75:55]

you don't have to be upset with yourself and you can be compassionate with yourself because you're trying very hard. And the fact that things don't work out and that there's problems is not your fault, it's the nature of human life. So I find that tremendously reassuring, actually. And the reassurance is just being in the middle of your experience, which is not just, by the way, of course, pain and difficulty, but there's also pleasure and the pleasure you have in your life is being with things. And when we're not willing to be with the pain, then, of course, we're also tending to distance ourselves from the pleasure. Because as soon as you're standing back and distancing yourself, then you're distancing yourself from all of your experience because you can't on the moment say, okay, let me see if this is going to be pleasant or painful. Now, if it's going to be pleasant, I'm going to dive in there. If it's not, then I'll hang back here.

[76:57]

Well, then you spend all your time hanging back and not allowing things to come home to your heart and not allowing things to touch you and not being touched by things and not touching things. And what about just being with things in a simple, direct way? And that's what gives us some happiness and fulfillment and joy and peace in our life because we're no longer struggling to get rid of these problems that it's inevitable that we have problems. The story I tell people is the one about... Excuse me if I go on and on about this, and I know other people have questions, but I love the story about the layperson who went to see the Buddha. Do you remember that story? And the layperson goes to the Buddha and travels a long time and offers his offering, and he says, I'm a layperson, my life is really difficult, and there's floods and there's famine. And I have difficulty sometimes with my wife, I get impatient,

[77:59]

and my kids, they're really great, but they're annoying at times too, and what can I do? And the Buddha says, Well, everybody has 84 problems, and as soon as you get rid of one, there'll be another to take its place, so you'll always have 84. And the layperson says, Well, what about all these monks and students here, they're all practicing these spiritual practices, it must be good for something, or they wouldn't be doing it. And he says, Well, sometimes it helps them with the 85th problem. So, of course, the layperson says, Well, excuse me, but what is the 85th problem? And the Buddha says, Well, the 85th problem is you don't want to have any problems. So, sometimes practice helps us with that 85th problem. Yes?

[79:02]

A bit more about the meditation process? Well, like everything else, it's out of control. So, regardless of how you'd like it to be, it will be what it is. And over time, you become then quite familiar with the whole range of what your life can be and what your experience can be. And you notice how you react to things, and in observing how your reactions work or don't work, then your life changes. And just by noticing things, your life changes. And it's not because you accomplish something in particular. Most of the powerful experiences for me in meditation have been to notice how completely impossible it's been for me to accomplish anything.

[80:17]

And then that's a big relief. Then I can just be with things in a much more simple and direct way instead of trying to somehow shape them, mold them. So, meditation is very much this kind of, what I've been talking about today, of the difference between trying to control and manipulate your experience and instead letting your experience come home to your heart. So whatever your experience is, you let it come home. You touch it and see if you can experience what it's like. And that basic effort of touching things and being with things is what is really quite healing, finally. What brings you tremendous peace and calm. Otherwise we're busy, you know what Buddhism says, is otherwise we're busy instead of just touching and noticing what it is, we're busy trying to grasp some things and push some things away which are already rising and disappearing.

[81:20]

So meditation, you know, a famous saying in Soto Zen from Dogen Zenji's Bendo Wa is famous and Kagura used to talk about it and say meditation is beyond human agency. Beyond human agency means beyond your particular endeavor to shape it one way or another. Meditation will unfold outside of that particular context, beyond your capacity to shape it. I mean your life is like that too, but meditation is a place where you can notice how much that's true. Yes? Yeah, there's an aspect of this that is like faith. What Buddhism calls it of course is karma.

[82:39]

That you will have experiences which are the result of causes and conditions including your past action in this life and your action in past lives. And to the extent that, you know, I don't know that I understand that or can comprehend it, but at this point I kind of take that on trust. And, you know, it's not clear why various experiences come to us from that point of view. One of Rumi's poems he says, he says if you can't do this work, meaning the work of, you know, being with your sickness and pain, you know, and going through what he calls, what he says is, you know, when you tan a hide,

[83:42]

you have to remove the hair and then you have to, there's some bitter acid that is worked into the leather and so this is quite a process, you know. And so he says the soul is like a bloody hide that needs to be tanned and there's the bitter tanning acid of grief and sorrow, you know. And so he says a prophet's soul is especially afflicted because prophets have to go through a lot to get their soul, you know, to have their soul purified and made strong. And he talks about a man who is a preacher who says, those who steal from me and, you know, I pray for them because they remind me of the things that I tend to want but when they try to steal it from me, I realize that that's not what I want. He says friends are enemies sometimes and enemies friends. Anyway, he says if you can't do this work, don't worry,

[84:45]

because life will bring you. The friend who knows better than you do, you know, the guest who's inside you and inside me will bring you joys and sorrows and pains and pleasures. You know, without your having to do anything. And so there's a basic, in terms of a certain fatalism, perhaps there's a kind of fatalism to that, but again, there's also the kind of relief. The release is, my life is already the Buddhist path and I can stop thinking that there's some other life I could be living where I didn't have to have this kind of experience. See, that's the fundamental, you know, from the Buddhist point of view, that's the fundamental delusion that we can imagine that there's this other life where I wouldn't have to go through what I'm going through here.

[85:47]

And what Buddhism says is this is your life already and this is the Buddhist path already and this is already the path of suffering and the liberation from suffering already. And so don't question that. Don't think that there's some other path where you don't have to go through this. And go through this and, you know, let it mature you, you know, like this tannin acid. Let your soul become strong, you know, by going through what you go through and be etched by what it gets, you know, by the scars and the lines. Let yourself become aligned. Don't think there's some life you would go through where you're completely immune and you never, and then you don't get marked and scarred. Don't think that. So that's a fundamental kind of reassurance in a certain sense that kind of, in a certain sense it's fatalism, but it also actually allows us to live our life.

[86:48]

With some confidence. This is my life and I'm going to, and I'll see it through and I'll do what I can with it. Yeah. Um. The phrase, let things come home to your heart. I think, for me, how it's easy to hear, easy to say, and very difficult to do, yet I know, and I think, it's like anger, for example. In that sort of thing, that's what, let it come home to your heart. But if I allow myself to experience it, it transforms. You know? And by experiencing it, I mean experiencing these bodily contractions. That's what it is. And because when I do that, I can't keep up that contraction,

[87:53]

I just can't do it, so it transforms into exhaustion. But getting to the point of allowing it... Being willing to do that. You know, that's always the mystery. You have to do it over and over again. I've done it a lot of times. But I can't do it every time. I can't say to myself, oh, I'm going to experience this. I'm going to let this come home to my heart. Even though I know, from having allowed it, that it's working great, if you're willing to do that in the past, I just can't always do it anymore. You know, letting your closed-heartedness

[88:56]

come home to your heart. And not being hard on yourself, or not being more open to things, or something like that. It also... I think it was Jung who... I'm not sure, but I think it may have been Jung who said that the heart has its reasons for things which only the heart can know. As opposed to... With reason, we think, well, I shouldn't be this way, or I shouldn't be so closed-hearted. I need to find out how to be more open. But accepting the own reason dictates of your heart. To me, that's also patience. Well, I'd like to finish this up. I brought you a little reading.

[89:56]

In the next week or two, I'm hoping to finish my book, which I've been working on for 7 or 8 years now. A lot of those years, I would just sit down at the computer and cry. Eventually, words actually started coming out of this process. So I thought I'd read you a little bit. I wrote a chapter called Tomato Ecstasy. So I'll read you some parts of it. Almost everyone has the capacity to taste and to discriminate between various flavors. Yet having the capacity doesn't mean that it is exercise. One reason it is underutilized is because people tend to be timid

[91:03]

about using language to articulate differences they've noticed. I find it fascinating how language helps to develop taste. Often when we cannot put a label on what we've noticed, it loses its significance. And conversely, when awareness has labels to attach to experience, suddenly details and nuances are relevant because they can be tagged. One example of this is professional tea tasting. According to an article I read, almost everyone with the appropriate training could learn to be a tea taster. Participants of tea tasting school are given 20 different teas and told, this is what we mean by bright, or this is what we mean by bold. Even though the 20 teas are different, they have this one common characteristic, bright, which the tasters are expected to identify, and another 20 are chesty or smoky or full-bodied.

[92:04]

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ