You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Monastic Evolution and Medieval Transformation

The talk explores monasticism in the 12th century, emphasizing the transformation in Europe from a Benedictine-centered religious culture to new schools of thought budding outside monasteries. Through historical figures such as Peter the Venerable, Saint Bernard, Peter Abelard, and Heloise, it discusses the tensions between traditional Benedictine monasticism and the emergence of the Cistercian order, detailing their divergent practices and philosophies. The narrative concludes by appreciating Heloise's role in maintaining a monastic order despite personal conflicts with faith, illustrating the enduring and transformative nature of monastic life through centuries.

Referenced Works and Figures:

- The Love of God and the Desire of Learning by a contemporary monk (introduction by Father Damascus): Noted for highlighting the scholastic contributions of individuals like Brian Tierney in the academic and monastic fields.

- David Knowles: Cited as a historian on monasticism, framing the Benedictine influence in shaping medieval civilization.

- Peter the Venerable and Saint Bernard: Key abbots representing the Cluniac and Cistercian monastic traditions, respectively, their interaction underscores the changes in monastic structures and spirituality.

- Peter Abelard: Exemplifies the intellectual ferment of the period with works like Sic et Non, which challenges established theological doctrines through dialectical inquiry.

- Heloise: Her life reflects the complexity of personal faith and institutional religion, revealing new monastic initiatives within feminine Benedictine contexts.

- Etienne Huisson and Teresa of Avila: Referenced for their insights into understanding the personal struggles of faith exemplified by figures like Heloise.

- Sic et Non by Peter Abelard: Illustrates the emerging scholastic method through posing theological questions that reflect the period's intellectual tensions.

- Saint Bonaventure, Saint Thomas, and Duns Scotus: Mentioned in contrast to 12th-century thinkers, showcasing the resolution of faith-reason debates in later medieval philosophies.

AI Suggested Title: Monastic Evolution and Medieval Transformation

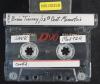

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

Speaker: Professor Brian Tierney

Location: Mt. Saviour Monastery

Possible Title: 12th Cent. Monastics

Additional text: Anniversary talk #1

@AI-Vision_v002

So we're having a little competition today in the Catholic sphere with one of the sisters at the Dominican convent having her 50th anniversary. But I would invite people to move up a little closer, if you want to, from the back. Now, this is the fifth of our lectures in our 50th anniversary. There was a book written by a contemporary monk called The Love of God and the Desire of Learning. And Father Damascus wrote the introduction to the book. It's quite well known in monastic circles, but certainly our speaker today, Brian Tierney, could have been the hero of the book if it was a novel or a biography, because certainly his contributions in the academic world, medieval history, his knowledge of church history and his development and his own life as a scholar is certainly something which is outstanding.

[01:11]

So we're very grateful that for most of us here who are not that familiar with the academic world to know something to increase our own love of God and desire for learning. So this is a perfect day to introduce someone like Brian. As you know, it's the feast of the birth of John the Baptist. And the Church has taken advantage, so to speak, of the fact that from around the 24th of June on, the light gets less, and there's less sunshine and less daylight. Then with the birth of Christ in December, the light begins to get stronger. So, in the immortal words of whoever said it, you know, I'm very happy that I must decrease so that Brian can increase. And those of you who know me, I'm happy that you'll get a chance today to know Brian. Thank you, Father Martin.

[02:23]

It's a great pleasure to speak to you this afternoon and especially on this auspicious occasion of the 50th anniversary of Mount Saviour. When I was thinking about this talk, I was reminded of the title of a best-selling book of a few years ago. It was called, How the Irish Saved Civilization. might be a bit more accurate to say that the Irish started to save civilization in the 6th century but then the Benedictines came along and finished the job. By the 9th century nearly all the great abbeys of Europe were following some form of the Benedictine rule and by some happy inspiration or intuition the monks of that time made it their task to copy in their scriptoria not only the scriptures and the church fathers but the whole corpus of secular Latin literature so far as they could and by doing so they preserved a whole heritage of early Christian and classical culture for future ages without their work there could have been no medieval civilization and of course no Italian renaissance

[03:40]

The monks really did save civilization in those long, dark centuries after the fall of Rome. The early 12th century, our period today, was also a great age of monasticism. Many new religious orders were founded at this time, and within the Benedictine family there came the sudden great flourishing of the new Cistercian order, literally hundreds of new monasteries in the space of 50 years. The greater abbots of that time were great feudal lords, often councillors of kings, important figures in Churchill's state. And yet, David Knowles, a great modern historian of monasticism with whom I once studied long ago, wrote of this period that it saw the end of the Benedictine centuries. And if so, it was because the world outside the monasteries was changing.

[04:50]

A new civilization was growing into existence. There was a sort of great awakening at this time of European culture, a new vitality in many areas of life and thought. The demographic curve had turned upwards, and with the increasing population, new networks of commerce sprung up and new city life. This was the age of the first great, soaring Gothic cathedrals. And also, outside the monasteries, new centers of learning were growing up in many cities, most notably at Paris. The greater masters of these new, more secular schools were opening up new pathways of thought. Richard Southern, their great historian, saw in their work a new kind of humanism, a human power to recognize the grandeur and splendor of the universe, he wrote.

[05:56]

Men were coming to believe that human reason could explore all the truths of nature and the truths of faith more than anybody ever had done before. It can all sound admirable, but it represents a radical departure from the old Benedictine culture, almost one might say a counter-monastic culture. The culture of these new schools was contentious and confrontational. The masters were ambitious, sometimes vain. They set up rival schools of thought and attacked one another. It all sounds a bit like Cornell, but we're a long way from the ten grades of humility in the Holy Rule. My task then will be to try to explain how the varieties of Benedictine monasticism interacted with one another and with this new intellectual culture of the schools.

[07:03]

Though I fear I shall leave you with more questions than answers about it all. Before I dive into it, I really have to offer you a sort of apologia. When Father Martin first asked me to do a paper on monastic history, I demurred. I pointed out that there are many technical source problems about monastic origins in the 12th century, and that I am no kind of specialist in that field. I have worked on 12th century thought a lot, but my interests were always in political theory and law. Father Martin seemed quite unfazed. In effect he told me to just get on with it. So I wondered how to proceed. And at this point I remembered the story of the man who was an expert on worms. He went to a conference and was a bit disconcerted to discover that he had been put down to give a paper on elephants.

[08:09]

Nothing daunted, he began, the elephant is a curious beast. Its most unusual feature is an extended proboscis. It is long and round, and indeed it is shaped rather like a worm. Now there are seven varieties of worms, and I thought I might attempt a similar sort of ploy this afternoon, but then I realized it would never work with such a sophisticated audience, and that I should have to talk about elephants, monasteries, I mean. What all this is leading up to is that quite truly I am not competent to give you a research paper presenting some exciting new findings about monastic life in the 12th century. All I can do is to try to present you a sort of general survey of some known material I'm very much aware that I'm going to be covering territory that will be familiar to many of you but it's a rich terrain so perhaps you won't mind traversing it once again and maybe every guide sees things a little differently Specifically then, I want to describe some varieties of monastic life, benedictine monastic life in the 12th century

[09:34]

the tensions that arose between the old-style Benedictinism and the new Cistercian model, and then I want to go and consider the deeper tensions between the contemplative culture of the monasteries and the new intellectual life of the schools. At the end we might for a moment just glance at Benedictine monasticism in our own changing modern world. I'm going to tell the medieval story mainly through the lives of a few individuals. Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny, Saint Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux, Peter Abelard of the schools of Paris, and his wife Heloise. And I'm taking this approach because The 12th century is often called an age of humanism precisely because at this time people were beginning to display a new sensitivity, a new concern about individual human qualities and their personal and emotional relationships and in their writings, letters, biographies, even autobiographies.

[10:42]

These people I mentioned all lived at the same time and they all knew one another. and their lives all intersected with one another at different points and each one of them can illustrate for us a different style of Benedictine life in the 12th century. Now that's quite obviously the case with Peter the Venerable and Saint Bernard but Peter Abelard lived several years of his life as a Benedictine monk and everybody has heard of Heloise as Abelard's young lover But we sometimes forget that she spent by far the greater part of her life as a nun. And in the life of Heloise as a nun we can find yet another tension in the religious life of this age. And this time it's a tension between the love of God and the passionate human love. The story of the relationships between these people is a story of conflict.

[11:44]

But it's also a story of reconciliations. Tensions arose in 12th century society precisely because the age was so fertile in inventing new forms of thought and feeling. But reconciliations were possible because of an underlying Catholic Christian culture that was common to all of them. So let's begin with Peter the Venerable and Bernard, Clooney and Clairvaux. and then move on to Abelard and finally to his conflict with Bernard. Peter the Venerable was educated in the Cluniac order as a child of late and he became Abbot of Cluny in 1122. Jean Leclerc described him as a symbol of monastic holiness fed at the sources of the Benedictine tradition. As Abbot of Cluny Peter was one of the greatest prelates of the Christian world at the time.

[12:48]

There were three or four hundred monks at Cluny itself and thousands more Cluniac monks in hundreds of dependent priories scattered all over Europe. So Peter the Venerable was the head of a great ecclesiastical empire. He was a man of ironic temperament. Among his works he commissioned a translation of the Quran into Latin and typically he wrote that the Muslims were to be approached not with force but by reason, not with hate but with love. Monastic life in Peter's Cluny was devoted to a daily perpetual round of liturgical worship that extended far beyond what the rule strictly prescribed. There were extra long readings at nocturnes, many additional psalms at each of the canonical hours. Saint Benedict said, I think, that nothing was to be preferred to the opus Dei, but at Cluny, you might say, there was nothing but the opus Dei.

[13:55]

Saint Anselm, the future Archbishop of Canterbury visited the monastery as a young man and he thought of becoming a monk there but then he decided against it because he realized that the daily round of liturgical worship would leave no time for study it also left no time for any significant manual labor and what little there was was turned into another sort of ritual at a shortened chapter meeting the abbot would announce that it was a day of labor The monks then formed themselves into a procession with the child oblates leading the way and processed out to the garden singing psalms. When they got to the garden they did a little bit of weeding singing psalms and then processed back into the abbey to get on with their real work of liturgical prayer. At Cluny the celebration of the liturgy was carried on in a setting of unsurpassed magnificence. The Abbey's Basilica, which was consecrated by Pope Innocent II in 1135, was by far the largest church in Europe.

[15:05]

No cathedral, no other Abbey, touched it. The capitals of the pillars were intricately carved with allegorical sculptures. The altar vessels were of gold. The altar itself was covered with silken cloth and illuminated with a forest of candles. the monks were praising the King of Heaven, and it seemed only fitting to them to honour their Divine Majesty with such splendid display. Spending many hours a day in choral prayer is not obviously a very easy way of life, but in some ways the monks did live less rigorously than the rule prescribed. They wore fine linen undergarments and fur-trimmed robes, and they enjoyed a rather lavish diet. The rule excluded any eating of flesh meat, but one can dine quite elegantly on fish and omelettes and game birds, and the monks did not disdain any of these delicacies.

[16:12]

One of the monks also noted that the daily pint of wine that was allowed by the rule was not nearly enough for monks who had so much singing to do. If we turn now to the Cistercian order, we encounter a very, very different way of life. Indeed, the Mother Abbey of Citeaux was deliberately founded as a sort of anti-cluny. It was founded by a group of monks from the Cluniac House of Molheim who became dissatisfied with that way of life, and they left Molheim in 1098 to found a new monastery dedicated to a strict and literal observance of the Benedictine rule. Everything at Cluny that was superfluous to the rule was stripped away. The hours of liturgical prayer were drastically reduced to make room for study, spiritual reading, and manual labor, and the monks really did do manual work in the fields or in the gardens every day.

[17:15]

Their diet was coarse bread and vegetables. All external signs of luxury were abolished. The monks wore only a simple habit of undyed wool. There were no silken altar cloths or golden vessels or elaborate decorations in the early Cistercian churches. But although the declared purpose of the founders was to obey the Benedictine rules simply and literally, they were also very much inspired by the early Egyptian monks like Saint Anthony, who had practiced more severe asceticisms than the rule itself insisted on and the critics of the Cistercians later on asserted that they were obeying the letter of the rule but evading its spirit. One of the critics wrote Saint Benedict did not introduce the customs of Egypt he said that all things were to be done with moderation. We can't get any further with Cistercians

[18:21]

without trying to understand the man who was principally responsible for the explosive growth of the Order, the one I mentioned, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, though I'm not sure that any modern scholar has really understood him, least of all me probably. Bernard was a man on fire with the love of God, and he had a gift of sublime eloquence through which he could convey his vision to others. At Clairvaux he lived a life of very extreme asceticism. All the Cistercians used a scanty diet, but Bernard at first tried to live on a mess of nettles and beech leaves, and naturally it made him vomit. And all his life he suffered from vomiting and stomach ailments, probably because of these early asceticisms. And yet, with extraordinary perseverance and fortitude, he became not only the inspirer of this great monastic order, but, it is often said, the spiritual leader of all Europe.

[19:24]

In the words of one modern scholar, he was a mentor of popes, counsellor of kings and cardinals, and maker and unmaker of bishops. Because of his reputation for holiness Bernard was often asked to involve himself in affairs outside his monastery and because of his passionate temperament he often involved himself without being asked. He poured out a flood of letters of counsel and often enough of rebuke not only to bishops and abbots but to kings and cardinals. When a former monk of Clairvaux became Pope. As Pope Eugene III, Bernard characteristically wrote for him a treatise on how to be Pope. One of Bernard's letters to this Pope later on began simply with the words, God forgive you, what have you done now? This was because the Pope had presumed to take the wrong side in a quarrel between two French Archbishops.

[20:29]

There's a paradox that everyone notes at the heart of Bernard's life. He always yearned for the quiet contemplative life of Clairvaux, and yet he always found himself in fact engaged in all these European wide affairs. Again, I think his letters will often strike a modern reader as harsh and abrasive for a great saint, even lacking in charity. But I think the truth is that Bernard loved Christ and he loved the church as the bride of Christ and he got filled with righteous indignation against anyone who he thought was sullying the purity of the church. Before we turn to the clash between these two, Peter the Venerable and Bernard, there is one last thing we should remember. It is possible even for a great saint to be wrong. when lesser people are right. On a point of theology, for instance, although Bernard greatly encouraged devotion to the Blessed Virgin, he strongly opposed the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception that was being debated at this time.

[21:46]

In the field of public affairs, too, Bernard had one great setback, his launching of the Second Crusade. Preaching through France and Germany, sure that he was doing God's work, Bernard inspired thousands of men to take the cross. For every seven women you can only find one man left, he wrote with great satisfaction. But many of those women never saw their husbands again. The Second Crusade was a disaster. The Crusaders were crushingly defeated. They achieved nothing in the Holy Land. The survivors straggled back to Europe, beaten and humiliated. Bernard himself was perplexed and dismayed. He could only write to the Pope that the judgments of God were dark and unfathomable. But he blamed the Crusaders, too, for being unworthy of their task. It never occurred to Bernard that he himself might have been mistaken in any way.

[22:50]

Two years later he was trying to stir up another crusade. Fortunately this time no one took any notice of him. Bernard's attack on Cluny came about at first almost by accident. He wrote to a young relative who had left his abbey of Clairvaux to join Cluny and live the less rigorous life there. Bernard wrote urging him to come back to Clairvaux. But the letter turned into a slashing attack on the whole Cluniac way of life. Referring to the prior of Cluny, Bernard wrote, this wolf in sheep's clothing commended feasting and condemned frugality. He called poverty misery and said that fasts and manual labor were folly. Bernard disapproved of the monk's clothing. warm furs, fine and precious cloths, long sleeves and ample hoods, soft undergarments.

[23:55]

And he disapproved of their diet. Wine and white bread, honeyed wine and side dishes. And then came a cutting phrase, the soul is not fattened out of frying pans. About the same time, it was probably about 1122, Bernard wrote an apologia that set out to be conciliatory. But when he came to the abuses of the old-style Benedictine monasteries, he couldn't restrain himself and he poured out another flood of invective. Not content with condemning again dainty food and soft clothes, he added this time a denunciation of Cluniac art and architecture. I will not dwell on the vast height of their churches, their unconscionable length, their preposterous breadth, their polished panelling, their candlesticks as tall as trees dazzling with precious stones. O vanity of vanities! Nay, insanity rather than vanity.

[24:59]

Peter the Venerable was on the receiving end of all this. He replied to a long list of Cistercian criticisms in a letter addressed to Bernard of Clairvaux, probably in 1125. Peter permitted himself one uncharacteristic outburst of exasperation. Oh, what a new breed of Pharisees has come into the world that separate themselves from others and prefer themselves to others and say, do not touch me, for I am clean Some of Peter's replies to particular criticisms might seem a little bit disingenuous. To allow for human infirmities, he pointed out, Saint Benedict himself had permitted two dishes at the main monastic meal, so that if a monk could not take one, he could eat the other. Well, Peter the Venerable argued, if two, why not three? And on the same principle, if three, why not four?

[26:04]

As for furs, the rule didn't say anything about them one way or the other. And besides, Elijah and John the Baptist were both dressed in skins. As regards manual work, it was not only rustic agricultural labor that was acceptable to God, Benedict had prescribed labor to avoid idleness, but a monk occupied all day in prayer and reading and chanting psalms was truly observing the rule in disrespect. Martha occupied herself with manual work, but it was Mary who had chosen the better part. I think it takes a bit of nerve to lecture Bernard of Clairvaux about Mary and Martha, but this was the abbot of Cluny. Peter's central real argument was that some precepts of the rule were unalterable, but others could be changed to suit changing circumstances, for good reason.

[27:08]

The rule was founded on charity, he wrote, and without charity no one could keep the rule. Any concessions to human frailty that you might find at Cluny were granted out of charity. But the Cistercians adhered to the letter of the rule while ignoring this first great requirement. Now I think you would have to be a Benedictine to judge fairly between these two. And I won't attempt it. There were real abuses at Cluny and Peter the Venerable himself tried to correct them later on. The dispute has been presented in many ways. Bernard was attacking the Cluniac ideal itself. It's been seen as a dispute between ritualism and asceticism, or sometimes simply as worldliness versus unworldliness. It also reminds me always of the dispute among modern constitutional lawyers about between strict constructionists and those who want to follow what they would call a living constitution, that you can adapt to changing circumstances from time to time.

[28:16]

In the 12th century, the Cistercians were claiming to be the strict constructionists, sticking to the letter of the rule. But really, neither side could reconstruct the way of life in 6th century Italy, or probe the mind of a man of that era. That way of historical thinking was not characteristic of the medieval mind. When they looked into the past, it was as though they looked into a mirror, and they saw only their own reflections. In fact, both Ceto and Cluny were departing from the rule, or adding to the rule, in their very different ways. Disputes between these Cistercians and Cluniacs continued throughout the lives of Peter and Bernard, and beyond, after they were dead. But at least those two, Peter the Venerable and Bernard of Clairvaux, soon achieved a personal reconciliation, and in their later letters they often expressed friendship and admiration for one another.

[29:27]

In spite of their different ways of life, of their communities, There was a bedrock monastic culture that they had in common based on the Benedictine rule. The situation was more difficult with Bernard's other most famous adversary, Peter Abelard, to whom we can now turn. Abelard was a champion of what I called the counter-monastic culture of the schools of Paris, a more questioning, doubting, intellectually adventurous culture. I need to remind you briefly of his stormy career. He won an early reputation in the schools for both brilliance and arrogance by attacking his first masters and defeating them in public debate. As a teacher himself, Abelard was by all accounts superb, attracting crowds of adoring students wherever he taught.

[30:28]

But with a personality like his, it's not surprising that when he wrote the story of his life, he called it a history of calamities. The first calamity, the love affair with Heloise, came when Abelard was in his late thirties, at the height of his fame. And you all know this story. Abelard went to lodge in the house of Fulbert, a Canon of Notre Dame. He agreed to act as tutor to Fulbert's niece, Heloise, a young girl who was already renowned for exceptional learning. The two fell in love, became lovers, and Heloise had a child. The lovers married, but Abelard wanted to keep the marriage secret for a time. The uncle Fulbert, furious and humiliated, apparently thought that he intended to abandon Heloise, and his revenge was to set a gang of ruffians to attack Abelard, and they left him sexually mutilated, castrated. After this disaster, Abelard tried to withdraw from the world by entering the great Bénédictine Abbey of Saint-Denis, near Paris, one of the great abbeys of France.

[31:40]

Heloise took the veil as a nun at Argenteuil, where she had been educated as a girl. This was Abelard's first attempt to live as a Benedictine monk. He was not very good at it. He soon quarrelled with the monks of Saint Denis by arguing that their founder was not the Dionysius the Areopagite, who was mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles, but some other, some quite inferior sort of Saint Denis. And then, for the first time at this point, Abelard's theological work was attacked as unorthodox. He was summoned before a church council, compelled to burn the offending book. And again he tried to withdraw from the world. This time he was granted a piece of land in the remote countryside 60 miles from Paris. He built himself an oratory there that he called the Paraclete and began to live as a hermit. But students came flocking out of the schools of Paris and insisting that he teach to them there in the wilderness.

[32:50]

Abelard and Bernard were very different people, as you would have gathered, but they both had a kind of charisma that made them supremely attractive to young people. Abelard's next move was another disaster. He was elected as abbot of St. Gildas, a remote monastery on the wild Atlantic coast of Brittany. But St. Gildas turned out to be a savage and dissolute place where the monks lived openly with concubines and their children. According to Abelard's account they tried to murder him when he tried to instill some discipline into the place. I'm afraid that's another kind of Benedictine life you can encounter in the 12th century. Though relatively rare by this time, there would have been a lot more St. Gildas's perhaps a century earlier. At some point, and the chronology is obscure, Abelard left this wretched monastery and returned to Paris, where he was soon dominating the intellectual life of the schools again.

[34:04]

Before we turn to his final conflicts, there's another style of Benedictine life which we ought to look at. In 1128, Heloise and the nuns of Argenteuil were compelled to leave their home because the abbot of Saint-Denis claimed that their land belonged to his abbey and he expelled them. So Abelard then granted his oratory to Heloise and to a group of nuns who followed her as their leader. And there Heloise settled. Heloise was much more successful as an abbess than Abelard ever was as a monk. Abelard wrote of her, and his words are confirmed by every other reference we have to Heloise, that bishops loved her as a daughter, abbots loved her as a sister, layfolk as a mother, while all admired her gentleness and patience. Abelard also mentioned that Heloise attracted more gifts in a year than he would have done in a century.

[35:08]

Among other things, Heloise was a good fundraiser. She would have made a splendid president of a women's college. In the famous correspondence between the two in the following years, Heloise at first wrote, as a woman still passionately in love, and that's the letter that everyone reads, that's the letter that's in all the anthologies. But then, the letters seldom read, Heloise wrote more calmly to ask Abelard for advice about the conduct of her monastery. I do not truly believe that Heloise needed any such advice, but she did very much want to keep in touch with Abelard. So she pointed out to him that although the Benedictine rule was observed throughout the Latin Church, it had been written for men. So what kind of a rule would Benedict have written if he had written a rule for women? What kind of clothes should they wear, for instance?

[36:11]

In offering hospitality, as the rule required, could male guests be admitted to the monastery? And what about diet? St. Paul said that Christians could eat any kind of food, but the rule excluded the use of meat. Again, Benedict wrote that wine was not really suitable for monks, and yet he conceded the use of it to men. Was it suitable for women? Aristotle said that women were less prone than men to become inebriated. But then Ovid said that wine stimulated lust. So what was to be done? And what about manual work? Did nuns have to labour in the fields to gather in the harvest? Abelard, having failed as a monk at St. Denis and failed as an abbot at St. Gildas, naturally felt perfectly qualified to lecture Heloise on how to run a convent of nuns. Fortunately, he gave sound and sensible advice. It has often been pointed out, though, that Heloise, although she asked for counsel, indicated pretty clearly what answers she wanted, and that Abelard usually obliged.

[37:21]

Surprisingly, perhaps, Abelard could be just as stern as Bernard in condemning monastic abuses. What was the use of abstaining from meat, he wrote, if monks ate vastly expensive dishes of fishes flavoured with peppers and fine spices? But Abelard also warned Heloise against excessive austerities. It was wrong to profess a rule of life that was too heavy to be borne, he said, and so risk breaking a solemn vow. The proper path, Abelard wrote, was to permit whatever was necessary to sustain nature, to maintain health, as I suppose we should say, while avoiding every kind of excess. So, the nuns were to wear an undergarment and a woolen habit, and they could have a cloak for very cold days. They should have two sets of clothes so that one could be worn while the other was being washed to avoid filth and vermin. And since some medieval ascetics considered it a virtue to be verminous, this was a sensible provision.

[38:27]

As for diet, they should eat simple food, coarse bread, and whatever else could be obtained locally, cheaply, and readily. Anything beyond their immediate necessities was to be given to the poor. Agreeing with Saint Paul and Heloise, Abelard did not forbid any particular kind of food. As for wine, if the nuns did not abstain altogether, they should at least mix their wine with water. Still, Abelard allowed three parts of wine to one part of water, which is not too bad. In their daily routine, the nuns followed a quiet, secluded way of monastic life. They rose at midnight for the night office and at dawn for the first morning office. They observed the canonical hours throughout the day. And the rest of the day was spent in study, that Heloise was especially qualified to instruct the nuns in, and in manual work, the sort of work that was considered proper for women in those days.

[39:36]

Washing altar cloths, spinning and carding wool, sewing, making clothes. If there were guests at the monastery, they were seated at a high table, and Heloise, the abbess, did not dine with them, but waited on them as a servant, and then took her meal with the other serving nuns. Any women who came to the gate seeking shelter were admitted, but men only with the special permission of the abbess. Heloise washed the feet of the poor women who came to her monastery. Well, there were various kinds of benedictine observance in the 12th century, as you have seen, but it sometimes seemed to me that the way of the nuns of the paraclete was as close to the spirit of the rule as any. We have to turn back finally to Abelard's more typical role as the champion of what I call the counter-monastic culture of the schools, and his conflict with the most zealous champion of the monastic way of life, Saint Bernard.

[40:43]

Abelard made very substantive, important contributions to medieval philosophy and theology. But what perhaps exasperated his conservative critics most of all was his whole style of arguing. It was typified in his best-known work nowadays, probably, called Sic et Non, Yes and No. In this work Abelard posed a series of theological questions, 156 of them altogether. And for each one he first presented a group of revered authorities proving clearly that one point of view was true. And then he produced a set of equally revered authorities proving equally clearly that the opposite point of view was true. And then he went on to the next question. And they were not Mickey Mouse questions. For instance, that God is one and the contrary. That without baptism no one can be saved. and the contrary, that good works do not justify man, and the contrary.

[41:44]

Abelard was not attacking the faith, he was pointing out that an adequate defense of the faith was going to require some critical discussion of the accepted authorities. He wrote, Abelard, by doubting we come to inquiry, by inquiry to the truth. But it seems the very opposite of what Bernard wrote. He wrote, it is more easy to find God by ardent prayer than by argumentation. Modern scholars have pointed out that Bernard was not hostile to all theological study outside the monastery, but he was certainly unhappy about the way theological questions were being handled in the schools of Paris at this time. When he addressed the students of Paris in 1139, he did not urge them to pursue their studies diligently, the better to serve the Church and the world, like a modern commencement speaker, Instead, he accused them of ambition, vain curiosity, and of course lust, and urged them to follow him into his way of life at Clairvaux.

[42:50]

And we are told more than twenty of them did so. In the next year, 1140 now, Bernard opened a direct attack on Abelard. He fired off a volley of letters to the Pope and various other dignitaries demanding that Abelard be condemned and silenced. The letters were written with all his usual vehemence. Here are some phrases from them. Master Peter Abelard is a monk without a rule, a fabricator of falsehood. And he has come out of his hole like a twisting snake. And he has gone before the face of Antichrist to prepare his way. And perhaps worst of all, he argues with boys and consorts with women. Abelard wrote that nothing could be believed unless it was first understood. But Bernard wrote, faith believes, it does not dispute, but that man, suspicious of God himself, has no mind to believe what his reason has not previously argued.

[43:59]

Another dispute that's hard to judge. The dispute has sometimes been presented as a conflict of faith and reason, but that's an oversimplification. They were both men of faith. Abelard wrote in his last letter to Heloise, I do not want to be an Aristotle separated from Christ. The real conflict was between an intellectual and an affective approach to Christian teaching, in which neither side, because of the personalities involved, could see what was essentially right in the position of the other. In 1140 a French church council dominated by Bernard condemned various teachings of Abelard. Abelard refused to accept the judgment and appealed to Rome and set out personally to plead his case there, but he fell ill on the way, as it happened, near the Abbey of Cluny, and Peter the Venerable persuaded him to stay there, even after news arrived that Abelard had been condemned at Rome.

[45:06]

And so, after all, Abelard lived out the last two years of his life as a monk. And in these last years the lives of Abelard and Bernard and Peter the Venerable and Heloise all became intertwined. Although the conflict between the first two, Abelard and Bernard, seems irreconcilable, even here there was a reconciliation, with Peter the Venerable acting as an indispensable mediator. Peter the Venerable had a great depth and breadth of understanding. He understood Bernard's saintliness and Abelard's intellectual greatness, and more surprisingly perhaps for a 12th century abbot, he even understood the lifelong love of Heloise for Abelard. Peter the Venerable and the Abbot of Citeaux anyway, between them, persuaded Bernard and Abelard to have one last meeting.

[46:08]

I wish we could know what they had said to each other. I wish they had tape recorders in those days. But however it was, they finally settled their quarrel, and Peter the Venerable wrote afterwards that they came together in a spirit of peace and their old enmities were laid to rest. And then when Abelard died, Peter the Venerable wrote to Heloise. I suppose the great Abbot of Cluny might have reproached Heloise for her role many years before in wrecking the career of the greatest scholar of the age. But instead, he praised her for her piety and learning. Peter the Venerable said that he had admired Heloise ever since he was a young man.

[47:10]

He only wished that her convent of nuns could belong to his Cluniac order. And then he told her about Abelard. David Knowles, to quote him again, called this a remarkable letter. You can judge. The last words, I think, are remarkable. Peter the Venerable wrote, It was given to us to enjoy the presence of him who was yours, Master Peter Abelard, a man always to be spoken of with honor as a true servant of Christ and a philosopher. No brief description could do justice to his holy, humble, and devout life among us. He was assiduous in study, frequent in prayer, always silent and less compelled to expound sacred themes before us. Thus this Master Peter completed his days. He, who was known throughout the world by the fame of his teaching, entered the school of him who said, learn of me, for I am meek and lowly of heart, and continuing meek and lowly,

[48:24]

he passed to him, as we may believe. Venerable, most dear sister in the Lord, the man who was once joined to you in the flesh, and then by the stronger chain of divine love, him, in your place, or like another you, the Lord holds in his bosom, and at his coming he will give him back to you, Such a letter could only come from an age of humanism and from a man of exceptional sensitivity. And in this case, too, we may remember one who was fed at the sources of Benedictine tradition. Subsequently, Peter the Venerable personally took Abelard's body to Heloise at the Paraclete, together with a pardon from all his sins for Heloise to hang over Abelard's grave.

[49:25]

And that would be the end of our story. Except that Heloise lived on for another 20 years. Her monastery flourished. More and more women came to join her until it was necessary to found a daughter house. And then another. And then another. Until when Heloise died, there were six daughter houses from the original foundation. She had established a new little order within the Benedictine family. And I mention this because there is one final mystery here about monasticism and the medieval mind. One last question for us all. Heloise always insisted in her letters to Abelard that she had no true monastic vocation. She wrote to him, it was your command, not love of God, that made me take the veil Some have seen in her conduct just a sort of pagan, stoic endurance.

[50:27]

But of course, Heloise was not a pagan. She was a medieval Catholic Christian, like all the other people we've been talking about. Only she was a Christian who was angry with her God. She thought that God was unjust for punishing her and Abelard after they had married, and so satisfied the law of the church. And so, she wrote, Oh God, if I dare say it, so cruel to me in everything. And so she felt excluded from God's grace. I can expect no reward from God, she wrote, for I have done nothing for love of Him. And there is the mystery. Could a woman in the 12th century live a model Benedictine life for 30 years, preside over a flourishing community and expanding community of nuns, elicit the love and admiration of everyone who knew her for her learning and kindness and gentleness, and still have no true vocation or no sense of God's grace?

[51:37]

Etienne Huisson, the great medievalist, wrote sensitively about this, and he quoted some words of Teresa of Avila. We women are not easy to know. You are wrong to judge us only from what we tell you. And of course, in the end, we cannot know the inner heart of Heloise. But I like to remember a belief of many medieval theologians who held that although no one can actually deserve God's grace, still we can trust that God will not choose to withhold his grace from anyone who does what is in him. Heloise did what was in her for many years. The Lord himself said, by their fruits you shall know them. And the last years of Heloise were very fruitful. The order founded by Heloise endured for centuries, until 1792.

[52:41]

And that can remind us that the end of the Middle Ages did not mean the end of monasticism. But the period we have considered did mark the end of the Benedictine centuries, in Knowles' phrase, in the sense that the monasteries were no longer the vital, indispensable centres of Christian culture that they had been in the earlier period. On the other hand, the schools of Paris continued to flourish, and by the end of the century they were transformed into a great university. About a century after Bernard died, his successor, the then Abbot of Clairvaux, established a school of theological study in the schools of Paris for Cistercian monks. Somewhat ironically, it was known as St. Bernard's College. In the 13th century, intellectual leadership passed to the new orders of friars, and the tension between an intellectual and an effective approach to Christian teaching that had seemed so intransigent in the days of Abelard and Bernard was finally resolved in the lives and works of St.

[53:53]

Bonaventure and St. Thomas and Don Scotus. But to come to an end, at last, We need not deplore the end of the Benedictine centuries. Saint Benedict never intended his monks to save civilization. That was the result of a contingent situation in an epoch far removed from our own. When we stand nowadays among the ruins of Cluny or the ruins of a great Cistercian abbey like Fountains or Rivaux, I think only of places I have visited over the course of the years. We may feel a twinge of nostalgia for a vanished great age of Christian monastic life. But it's an illusion. The rule of Saint Benedict is no more purely medieval than Christianity itself.

[54:56]

It's the way of life for some chosen souls in every age. And it seems particularly fitting on this special occasion to celebrate the renewal and continuity of Benedictine life here in the Chapel of Mount Saviour. I think that if Saint Benedict could see the stately magnificence of Cluny and the fierce asceticisms of Clairvaux, he might scratch his head a bit and say, all this is splendid, of course, But it's not exactly what I had in mind. And yet, he might feel at home here, in the wilds of upper New York State, in a land he could never have dreamed of, for he would find here another way of life in accordance with the rule, a life of simplicity and stability and community. He would not be upset that his monks were not involved in great affairs of state, nor striving to save civilization, except in so far as our secular civilization will always need their prayers.

[56:09]

But he would see them exercising a kindly influence on many individual lives through that most benedictine virtue of hospitality, which in our age can be expressed not only in the reception of casual visitors but in the retreats and conferences that bring a widening circle of seekers and pilgrims here to Mount Saviour to find refreshment and peace and spiritual renewal. So I will end with some words that were written in a quite different context and yet it seems not unfitting to read them here. The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts. And that things do not go so ill with you and me as they might is half owing to the number who lived faithfully hidden lives and rest in quiet graves.

[57:15]

I suspect that the monks of St. Mount Saviour will give better answers. kind of relationship. It seems like you have virtually a divestment between the poor versus people who do something for all of us. Because you have to go by a luxurious life, not a sympathy dynasty. He is not asking for questions about applying the facts. In some way, and if you said that he speaks of the 1580s, more of this is what he knew than what I got. But indeed, we can agree that some kind of helpful probability, I think, is a possibility.

[58:46]

Values are needed, it's necessary. As a result, some of the great Benedictine monasteries do run colleges. There are many Catholic universities, that you know. My own Cornell was an intensely secular course. I don't know quite how to respond. Cornell was known as Goddard's Cornell when it was first founded, but it didn't have a religious affiliation. But anybody that wants to make a religious life can, of course. There are chapters, many denominations, including South Africans. And for a minority, there's a vigorous religious life going on.

[59:46]

And perhaps a lot of dressing rooms. Questions could come up more than those two, which is pretty helpful to have effective answers. I don't know whether you were here at Mount Saviour or where people come from Cornell. I meant sort of official visits. There can be an interplay between the monastery and the university for those who are seeking. Yes. You mentioned that the Qur'an has been translated into Latin in the late 4th or 5th century AD. It was written in the early development of the stack of, you know, all the five countries in Muslim religions, Egypt, Medina, Qusayr, and Greece.

[60:58]

Thank you, I am making a promise to the mother of my little son. Not while I'm speaking, but while I'm studying. I think, at least, because my son is studying, very good for him, so I'm providing it. So, it wasn't a rejection, I think, in the end. I asked her to speak loudly on the commute. I finished the game, I will be in tomorrow. By the end of the week, I will be sitting at home, sitting on the couch, I was pleased to spend so much time with Always. Would you say that Gunther's monastic life and networks are men's monastic life, and what would be the outcome? I'm very excited to see what the outcome will be. But there is a song that we have linked to.

[62:11]

Angel of Sarkar said to me, he said, Angel of the Prophets. And the way he put it, [...] he said, Angel of the Prophets. And the way he put What is that? Instead of people looking to the past, they look to the other way.

[63:19]

Going on to, uh, after a little while he told my step-sister, I mean, uh, the way he reduced the bedroom, looked at the drawers, and he saw, and suddenly found bedroom, which is the very second door on the right, and it's down there, and it's the first door on the left, and the other two doors, and he said it was very easy to find one on the right side of the room, and then he got into the living room, and saw, and it was there, and he used it. Yeah. For, uh, finally to go through all the stuff, and I thought, you know, I've got nothing wrong with this. So my question is, and when it's a quick turn back, what would a scholar, who is a woman, like Elodie, see when she looked to the past? Would she see both of those? Because it's her vantage point. She must have looked to the past too. And was there something there that hurt you, Freddie?

[64:40]

I hated him. He was the final martyr. He was the greatest soldier. He was the chief of guerrillas. He was also arrogant. I thought that was a roadblock of a path to the Greenwich. I mean, there are a lot of other people who would want to ask more, but I can't say. It's just that I don't want to be the kind of person that gets the thing wrong. But it did seem to me that there was a bit more of a problem yet. It's a bit of a pickle though, in a really broad language. I was just thinking of the woman in the scripture and whether or not the very rabbi there is a mother of all I want and the woman there, that's an interesting I don't wonder if she ever wrote anything about those examples.

[65:52]

It is difficult. I don't know. [...] He's definitely very young, and he's a very well-structured person, and he's a very well-rounded person. I think that the lectures that I want to offer will be very positive, particularly if you are a vegan. I'm very glad that it's particularly true of These are the elements that must be noticed and assessed. There are the faults of each other, which is, you know, generally considered to be the primary difficulty that we must have.

[67:01]

I hesitate to talk a little bit more because I think it's really important. I believe one should be able to stop that and be able to move on from the result of the threat of those robots and find a way to move on. If the only robot was the same as the others, well, it's not a problem. Or if there are other actions that might sound like that, it's not a problem. It would be illusive to do that. It's very difficult to make sure from multiple sources if you want to share it, but Canada has long since been a legacy of ours, and he likes it, and he likes it. And, however, it's a further thought, the natives are also some of the most extraordinary people in the world. It's more than possible to say that Australia is the country of the heart, and I don't know how to make that answer.

[68:04]

Well, Brian, thank you very much. It doesn't work too well if we have a break of any length of time, but it probably is good if people would simply stand up and stay where you are. And then we'll begin and have vesters in about two or three minutes. Go ahead. future.

[68:50]

@Transcribed_v004

@Text_v004

@Score_JI