You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Simplicity's Sacred Space in Design

Simplicity in Art and Architecture

The talk centers on how Benedictine spirituality, notably the principles of hospitality and simplicity, informs the speaker's work in art and architecture. The discussion covers personal influences, interpretations of these principles, and presentations of various images reflecting their aesthetic. It includes references to historical monasteries and influential architects, highlighting the relevance of simplicity in artistic and spiritual expressions.

Referenced Works:

- Benedict's Rule, Chapter 53: Discussed within the framework of Benedictine hospitality, stating that guests should be received as Christ himself, emphasizing openness to new ideas and people.

- Simone Weil's Quote on Beauty: "In everything which gives us the pure, authentic feeling of beauty, there is really the presence of God" supports the idea that beauty manifests divine presence.

- Architectural Works by Andrea Palladio: San Giorgio Maggiore reflects classical architecture's integration with simplicity in design.

- Ronchamp Chapel by Le Corbusier: Examined for its emotive design and innovative use of concrete, demonstrating simplicity.

- Subiaco Monastery: Highlighted as a foundational site for Benedictine monasticism, illustrating architectural and spiritual simplicity.

- Montecassino Monastery: Noted for preserving learning traditions while embodying aesthetic simplicity.

- Works by George Nakashima: The chapel furnishings at Mount Savior embody simplicity through masterful craft.

- The Rose Center for Earth and Space: Cited for its geometric simplicity and use of modern materials.

- Corning Museum of Glass: Notable for its simple, yet innovative architectural design.

Influential Figures and Architects:

- George Nakashima: Renowned for simple and functional design, particularly in religious furnishings.

- Le Corbusier: Known for innovative use of concrete and architectural simplicity.

- Simone Weil: Provided philosophical support for the connection between beauty and spirituality.

- Kevin Roche: Architect of Corning's headquarters, known for integrating simplicity with modern architecture.

AI Suggested Title: Simplicity's Sacred Space in Design

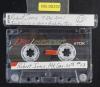

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

Speaker: Robert Ivers

Location: Mt. Saviour Monastery

Possible Title: Simplicity in Art + Architecture

Additional text: Benedictine Tradition

@AI-Vision_v002

As you know, there's a famous place that says that you save the best till last, and all kind of comparisons are odious. And we've certainly been very pleased with the people who have spoken to us in the course of this year. But as I said, the last few speakers, Sister Marie-Juliane, Sister Camille, and now Bob, have been people closer to the monastery in the course of time. And so in a sense, their presentations are a little closer to home, and so they're more pertinent and more enjoyable in many ways to us. So we're very pleased that Bob Ivers has agreed to speak to us and present these slides. And again, as I said and will say once more, we don't go in for large-scale introductions because it's the people themselves you've come to hear. And I'm doing this in part to give Brother Gabriel time to get to the

[01:04]

speaker and turn all the motors on. So, Bob, I think it's time for you. Well, first of all, thanks for coming. I didn't know how many people would be here with the weather we had. We have a gorgeous, gorgeous afternoon, as it turns out. Everybody can hear me? Just press one button's forward, the other's back. You want to go back? There you go. Well, I'm honored to be part of the events here at Mount Savior Monastery and help celebrate the 50th anniversary.

[02:11]

It's a wonderful place, spiritual, nurturing, and community. And I'm grateful to be included among the Oblates of Mount Savior. At the outset, I must say that it has been a memorable year. the lectures, the concerts, the receptions that we've had. And Mary Ellen and I would like very much to express our heartfelt thanks to Father Martin, to the monks, and to all the planning and implementation team who made all the events possible, particularly to Marie Colucci. And I know Andy has been a great help in this as well. And John Bowler has been the coordinator of all of these lectures and all the people who have helped set up chairs, et cetera. So just our personal thanks to all of you. I think it's been a wonderful, wonderful summer. My talk will be somewhat different than is advertised. That's nothing new, is it?

[03:12]

And as Father Martin outlined this morning, it was news to me. He told me what I was going to be talking about. But there'll be no burning bushes and no banana trees or any prophecies being made at all. But I have changed the agenda a little bit. And rather than talking about Benedictine art and architecture, I'll try to convey to you how I've been influenced by Benedictine philosophy and traditions, both in my work and in my life. And that was the original charge to this series of speakers and how the Benedictine influences, what kind of influence it's had on us. And my comments this afternoon will be, one, relate to you how I developed my relationship to Mount Savior. Two, to propose a personal interpretation of two of the primary tenets of Benedictine philosophy, namely, hospitality and simplicity, both of which have influenced my work as a designer and a painter.

[04:16]

Three, I'll follow with the slide images that illustrate my interpretation of Benedictine hospitality and simplicity. as expressed through Benedictine monasteries, churches, my favorite chapel, as well as many secular buildings. And four, I'd like to show you some of my work and work of others whom I've influenced as a director of design in my other life. And finally, I hope you have some questions and some challenging questions and we can have some discussion. So that's the format for the talk. First, my association with Mount Savior. It was a bright and very cold winter day many years ago when my wife, Mary Ellen, went for a drive to see the area that had just become our home after being transferred from New York City to Corning. I remember the day very clearly. I was working at my drawing board in our newly rented apartment in Elmira. My one-year-old son was napping.

[05:18]

An hour or so later, Mary Ellen arrived extremely excited about a discovery she had made on a hill a short distance from Elmira. She had discovered Mount Savior. Thus began a long relationship with the monastery and the spiritual nurturing of the Benedictine tradition. We were privileged to know Father Damasis and all the monks during those early years. Damasis had a keen aesthetic sensibility and a knowledge of the arts. He took great joy in talking about the beauty of the monastery and the history of some of its artifacts. He asked me to design several publications and booklets for the monastery and to assist in presenting craft shows on Dedications Day. In those days, the Dedication Day was a very ambitious undertaking. We literally had thousands of people here. We had a very major craft show, and it was before all of the other arts and crafts for shows that are being held in the area. It was not very long until I learned about Benedictine care and concern for the holiness of simplicity and good work.

[06:27]

It was reflected in all the outward manifestations of their tradition, the design of their places of worship, their liturgical vestments and artifacts, and in being good stewards of the land that graced the monastery. Several weeks ago, Sidney Callahan spoke here I asked her a question about the role of beauty in overcoming suffering or helping to relieve suffering. For this to happen, we must be able to recognize what beauty is, to perceive sharply, to listen acutely, to sense the sacred in all things, in people, in music, in painting, in poetry, in nature. Mount Savior and Benedictine life have broadened my consciousness and concept of beauty The focus of this talk, as I said earlier, is not to present a history of Benedictine art, but rather to illustrate how Benedictine spirituality has influenced my work.

[07:29]

It is about the formation of my own aesthetic, my own point of view, which might be different from yours, and it's about how I've influenced and made decisions about architecture, the design of forms for objects with which we work and play, and the crafting of images that convey utilitarian and inspirational ideas. It's about the principles of simplicity and beauty. It's about beauty through simplicity in all things. Simone Weil has said, quote, in everything which gives us the pure, authentic feeling of beauty, there is really the presence of God. There is, as it were, an incarnation of God in the world and it is indicated in beauty," unquote. Beauty is the icon through which God reaches us. The experience of God does indeed reach me through beauty, certainly through the beauty of benedictine liturgy and through people.

[08:35]

But perhaps the way the genes lined up, God touches me through the painting of young and old, through architecture, sacred or secular, through music, dance, poetry, and theater, all the arts. And during a lifelong career in the arts, in design and painting, I've formed my own point of view about beauty. Again, if you will, my own aesthetic. We all have many influences on our lives, our careers, and on our values. And I've come to realize that although there have been many influences on the direction of my life and my development as a designer and painter, there are two tenets of Benedictine of the Benedictine rule that have had a great effect on my formation. And those two are hospitality and simplicity. And I'd like to approach Benedictine hospitality and simplicity with a broader and more personal interpretation and perspective. First, let's discuss hospitality. We think of hospitality as kindness and in the welcoming of strangers, a generosity towards others.

[09:43]

Chapter 53 of Benedict's Rule is concerned with the treatment of guests who are to be received as, quote, Christ himself. Benedictine hospitality is a feature which has in all ages been characteristic of the order. For centuries, monasteries have traditionally been a haven for the weary, strangers in need of a meal or a bed, pilgrims looking to deepen their faith. Hospitality is all of these things and more. If we think of hospitality, however, in a much broader sense, it can mean an openness not only to people, but to new ideas and insights. Hospitality can be a state of mind that welcomes and encourages fresh thinking. Hospitality can expand our horizons in the arts, in the sciences, and in our own spirituality. This broader definition of hospitality has helped me to form a personal aesthetic

[10:45]

and approach to the arts and design in all I do. The second tenet, simplicity. In Benedictine communities, there is a great yearning to live more simply and contemplatively. The desire for simplicity touches the heart of the monastic vocation. Monks down through the ages have been engaged in the search for simplicity at the source. The monk believes that the absolute is simple, and that the goal of life is to attain that very simplicity. The core of being is, in fact, simplicity. Simplicity is the mark of the master hand, whether the creation is a chair, a poem, a building, or a sermon. We have a rich environment of simplicity here at Mount Savior. The simplicity of concept and design of the chapel furnishings by George Nakashima, one of our country's master craftsmen, the vestments of the monastic community, the chalices, and the simplicity of the altar table.

[11:49]

We are fortunate to be able to cherish and to explore the vibrant simplicity of faith and grace that the environment of Mount Savior provides. Now, in our time, simplicity in the arts and in life is difficult to achieve. Indeed, it is not easy in my own discipline as a designer and painter to reach this goal. The process is really ongoing. To achieve simplicity in artistic expression and in our spiritual relationship to God in all life's endeavors is not simple. I've found that simplicity can only be attained in my own design and artistic expression as I gradually learn to eliminate details. As I continue to struggle to master the details, I can suppress them. When I look at a design or a painting, I ask myself, what can I eliminate to make the final solution more accurately reflect the function of an object or a building, or the essence of the expression of a painting?

[12:51]

Not what can I add, but what can I subtract? I like to think that this personal philosophy and aesthetic reflects one of the highest aspirations of simplicity found in the Benedictine rule. Now, if we think of it, At the core of all profound artistic expression, scientific inquiry and effective living is simplicity. The simplification of form to its fundamental geometric shape was a great innovation of the painter Matisse. Beethoven constructed and composed his great symphonies using themes and variations using only several basic notes. Einstein posed simple questions to himself about the universe before he was 16 that were to be the substance of his life's work. He was aware of the parallels between his thought patterns and those associated with children. Children's questions are direct and unsophisticated.

[13:53]

They are simply stated. My 10-year-old granddaughter, after learning about the World Trade Tower disaster, said, why do people do such things, Papa? Her question was a simple one pertaining to the nature of human relations and the question of evil. In the dance arts, Martha Graham simplified the form of the body to achieve more expressive emotions in modern dance by covering the body with a shroud fabric. She worked intensively to simplify her dances, paring them down. And now as I think of it, we think of the monk's habit does the very same thing in simplifying the entire body. Both of these characteristics, hospitality and simplicity, have provided spiritual insights that have influenced the decisions I've made as a design director working in industry, an architectural design consultant, and in recent years as a painter. It's very exciting to realize that hospitality toward people can foster openness to new ideas and concepts.

[15:02]

that creativity nurtured by simplicity can result in experiencing the reality and essence of things. I'd now like to show you a rather eclectic presentation of images, churches, monasteries, secular buildings, as well as corporate projects and paintings that reflect my aesthetic point of view and the influence of hospitality and the simplicity of Benedictine. John, can you start that? Let's see, where does that go? Let's just go back to the first slide a minute. Again, this is just to reinforce the idea of hospitality being open to new ideas and new concepts in addition to being open to people in all areas too. It's not just the arts. Scientists will tell you the solutions are very simple.

[16:03]

They're right there all the time. It's just pushing away the details and getting to that solution. Okay, second slide. Just a little background. Benedict was born in 480 in Nursia, Italy, a village high in the mountains northeast of Rome. His parents sent him to Rome for classical studies, but he found that life in the eternal city not to his liking. He left Rome. went to a place southeast of Rome called Subiaco, where he lived as a hermit for three years, attended by the monk Romanus. The hermit Benedict was discovered by a group of monks who prevailed upon him to become their spiritual leader. Benedict established 12 monasteries with 12 monks in each of the areas south of Rome. Later, around 529, he moved to Monte Cassino and founded his premier monastery, Benedict died at Montecassino in 543. He wrote the rule for the community in Montecassino, though he envisioned that the rule could be used elsewhere.

[17:07]

Saint Benedict did not establish the monastery of Montecristo in order to preserve the learning of the ages, but in fact, the monasteries that later followed his rule were places where learning and manuscripts were preserved. I'd like to show you several monasteries that I've visited. which represent conceptual diversity and openness to the architectural influences of their time. And I'll begin with Subiaco. This is a fascinating monastery on a rugged Italian mountainside. And this is the monastery of Saint Benedict at Subiaco. It's the first monastery founded by Saint Benedict over 1,500 years ago. And he was, at that time, about 20 years old. Father Martin introduced us to this monastery several years ago as part of a Mount Savior trip. The monastery is reached after a long climb and stands on a rocky base overhanging the valley.

[18:10]

As you can see, it is integral to its surroundings, the mountainside itself. Okay? Benedict lived here three years as a hermit in a grotto on this site And this small, obscure grotto of Subiaco became the cradle of the Benedictine order. That's where it all started. Benedict founded 12 monasteries in Italy. And if you go into the inside of this monastery, this is an interior view of it, there's a statue. And seated within this roughly walled gray chamber of the monastery is Benedict in snowy white marble, contemplating the cross in a wicker basket made out of the same stone. As I said earlier, a monk named Romanus kept them alive by lowering food in a basket through an opening in the ground. Very sparse fare most of the time. Probably not pasta or lasagna, I'm sure. Benedict moved on from Subiaco and then founded the Monastery of Montecassino.

[19:17]

The Monastery of Montecassino has also been called the Cradle of Benedictine Order. St. Benedict founded this abbey in 529 A.D. The site for this monastery, like many others, was on top of a mountain. The monastery was several stories high and was completely destroyed in World War II by artillery fire aimed at German defensive positions in the mountains. The tombs of St. Benedict and his sister, St. Scholastica, survived. After the war, the monastery was rebuilt in conformity with the original plan. And this is an interior view of the courtyard at Monte Cassino, and it's done in the classical Romanesque style. This is a monastery in Switzerland, Descentis Monastery, another Benedictine monastery. I traveled there by train to see this monastery.

[20:21]

It was established in the 7th century. This monastery had many architectural rebirths and restorations over the period, over the centuries, rather. And the new building dates from 1656. That's true of all of these monasteries. If you look at them in the 700s, 800s, and the Middle Ages, they've all had many, many iterations of rebuilding and redesign, and most of them are like this. This is the interior. It's done in an early Baroque stucco style. The paintings in the church represent scenes in the life of Saint Benedict. You can see the interior is hardly simple. During the Middle Ages, there was a general problem concerning why monastery should be concerned with art at all. It seemed to be a conflict, a philosophical conflict about the monk being out of the world and not surrounded by any embellishments at all. That argument and problem went on through the Middle Ages.

[21:24]

But often patronage in the architectural style of the period determined the extent of embellishment in churches such as you see here. In later years, monastic reformers made a point of including simplicity and austerity in their program and in their architecture. And this particular approach is not the aesthetic that I've adopted in my own life. But it's a very good example of the Rococo style of the period. This is San Giorgio Maggiore. I'm sure a lot of you have probably seen this. And this is Benedictine Abbey situated on an island in Venice Lagoon. It is the work of Andrea Palladio, the most important architect of the 16th century. It's been occupied by Benedictine monks since 982. In 1566, Andrea Palladio started a new Renaissance style of building influenced by classical architecture.

[22:25]

The church, the tower, and the monastery form a very successful grouping visible from the Piazza San Marco. The interior of this monastery has three naves and is built on a cruciform plan. And the lines of the interior, as you can see, are classical. with half columns that support the arches. A single dome crowns the central nave. The entire interior scheme is in white. It's very rich and very simple. And this abbey, though executed in the classical style, is essentially composed of three simple forms, the church, the tower, and the monastery itself. Reichenau, this is a monastery in Germany. It was founded in 728. Now, I have not been to this monastery, but include it because it is consistent with similar influences on the formation of my own aesthetic.

[23:27]

In appearance, the building is simple, but massive. It reflects the high standards of monasticism, where magnificent transcripts were produced dealing with every subject, theology, music, the natural sciences, and philosophy. The interior is very direct in its allocation of spaces and materials. The monastery, like most early monasteries, underwent a great deal of rebuilding and new construction. This went around 1048. The frescoes are from the 13th century and depict the life of Christ. It was in this church that Sabe Regina was first heard, the chant that is used at the end of compines throughout the world by benedicting monks. This is a very favorite monastery of mine. This is a sketch that I did of Sant'Antimo. And this monastery is not on the top of a mountain, but it's in a valley. And the abbey of Sant'Antimo is in Tuscany, south of Siena.

[24:35]

The original abbey was constructed in the year 800. Tradition holds that in 781, as he was returning from Rome, Charlemagne passed by Montantimo with his court and army. Many of his men were afflicted by disease. In order to stop the epidemic, the emperor made a vow, and in thanks for the healing, he founded the Abbey of Sant'Antimo. This structure dates from the 12th century. It was designed by a French architect and executed by artists from France, Lombardy, and Pisa. It's one of the most significant monasteries of that region. As I said, it's located in a marvelous valley, and unlike other monasteries that I've shown you, it's not on top of a mountain, but I love the simplicity of it. It's beautiful austerity of this monastery is surrounded by nature and far from the noise of towns and roads. We had a splendid luncheon banquet with monastery friends at a family restaurant overlooking the monastery, and I spent a great deal of time doing sketches from the top,

[25:44]

The restaurant was located on most of the Tuscan landscape. I don't have the sketches, slides of those sketches. Just some other views of Sant'Antimo. Okay? Okay? And this is the interior, the light in that interior. It's completely white and it's ethereal. It's very simple, as you can see, but I've never experienced the kind of light that was in that structure on the day we were there. Just a brilliant kind of glowing environment. Some sketches I did of the monks at Sant'Antonio. Mount Saviour. Now, Saviour was founded in 1951, for those who don't know that. The monastery complex follows a typical monastic plan developed by Benedictine monasticism.

[26:52]

It includes a church, usually, an adjacent cloister in the shape of a courtyard. And around the cloister is generally, you can find a library, chapter house, a dormitory, a refectory, a kitchen, and cellar. And some monasteries have some other buildings. Those are the essential parts of most monasteries, and all of this space is essential for the daily monastic regimen. I've always admired the simplicity of the chapel at Mount Savior. A friend of mine, Ron Cassetti, designed this monastery, not from the very beginning, but it was done several years later. The altar table couldn't be more direct. in design. It's a stone monolith table supported by a stone pedestal. The furnishings were designed by George Nakashima, as I mentioned, the most renowned wood craftsman in the United States. And next time you're in the chapel, really look closely at the detailing of these wonderful furnishings.

[27:59]

Every element in their construction is simply conceived. Nothing can be added, nothing taken away. Each satisfies its function in a beautiful and simple way. This sculpture of the risen Christ marks the monk's cemetery. As you can see, it is composed of three materials, wood, polish, granite, and metal. To me, the outstretched arms of this risen Christ embrace all people, but seem to embrace the glorious countryside and the hills of Mount Savior. These are two views of the interior of this monastery, the entrance to the library, and the room where we're now occupying. This sculpture of the Good Shepherd marks the Lay Cemetery. And probably a lot of you haven't walked up this hill to see that Lay Cemetery.

[29:00]

But that's where this sculpture is located. It's a very successful expression. It's beautifully stylized. a shepherd, a lamb, and the countryside represented by the tree trunk. And there are many, many rich artifacts at Mount Savior. The liturgical chalices, the vestments, of course, a statue of Mary, and the altar in the crypt, as well as weavings by Brother Stephen, paintings by Brother Luke, and icons by Father Alexis. I must say that the imagery of flocks of Mount Savior sheep against the meadows and the sky are treasures of Mount Saviour as well. I'm not sure at times whether Brother Pierre or the other members of the community would describe them as treasures, however. Simplicity. At the core of all profound artistic expression is simplicity. I'd like to show you

[30:04]

three buildings, pictures of three buildings that reflect this simplicity. This is the Rose Center for Earth and Space. It's in New York City. It's one of my recent favorite buildings of mine. It's part of the old Museum of Natural History in New York. A very, very simple design concept expresses a sphere within a cube. The simple geometric forms combined with modern materials give this structure the power of an icon. The Rose Center is clad in the largest suspended glass curtain wall in the United States. The glass cube is 95 feet high and is made of nearly an acre of glass, 36,000 square feet. The sphere housing the planetarium is 87 feet in diameter and is clad in aluminum panels. The building is an elegant sight at night, as you can see. Again, beauty through simplicity.

[31:07]

The architects, the Polchek partnership, and the exhibits in the building were done by Ralph Appelbaum, who did the exhibits for us in the new Corning Museum of Glass. But very, very simple architectural concept. Sphere within a cube. OK? This is my favorite chapel in the world. This is in Ronsham. France. I'm sorry I didn't look that side. This is a sketch of this chapel, Rhone-Champ in France, as I was approaching it. It sits on top of a hill. Next. Another sketch of the chapel itself. You'll understand that more when you see the photograph. Okay. This chapel is by the architect, Again, it's another example of a very simple conceptual approach to the design of a building. It's completed in 1955.

[32:08]

Now, unlike the Rose Planetarium, which you just saw, Ronschank has a complete absence of geometric forms. Its design is curvilinear throughout. But Mary Ellen pointed out to me that the windows are rectilinear. I've always thought that the sweeping roof of the building resembled a nun's habit. For many, many years I thought, you know, it's one of these monks, these nuns' habits from a convent in Europe. Well, as it turns out that the form of the building, according to Corbusier, was inspired by the shape of a crab shell that he picked up one day decades earlier while visiting Long Island in the United States. So that shocked my whole romantic idea. But anyway, it's a very simple idea. But it's really inspired me as an example of openness to new thinking and an example of how beauty can be achieved through simplicity. It's a magnificent structure.

[33:10]

It's poetic on the outside and soothing and simple on the inside. I might show another slide of that. This is the slide of the inside. And last week, in fact, I read a review of the book, a book titled Architects on Architects. And one architect wrote of this building, Corbusier's Chapel, quote, because of the overwhelming spatial experience which penetrated deep into my soul, I had to leave after staying less than an hour. And I was awestruck by a light unprecedented in my life, end quote. I made a pilgrimage to Rongshan to see this chapel. It was a very special time for me and a very special spiritual experience. My daughter was receiving her first communion back home and I couldn't be there at that time. It was a business pleasure trip. I spent the night in one of the little houses on the perimeter of the church.

[34:10]

The house was actually covered by turf. The site of the chapel is very similar to Mount Saver, on top of a hill. A very small chapel that holds about 50 people. And there is an open altar on the outside of the chapel where people congregate for masses, but the inside only holds 50 people. I must tell you that I visited the great St. Paul's Cathedral in London two days later, and as magnificent as it is, with the sounds of its carillon pealing across London, my heart remained at Roanchamp, inspired by its simplicity. and the experience that was very profound to me. Wherever I go, particularly in architecture, I try to do sketches of most of the things that I see. This is the bell tower of that chapel. This is where the carillon is. The entire building is made out of concrete.

[35:13]

Even that big roof that you saw was reinforced concrete. The third example of a very simple concept for the building is the Corning Museum of Glass. This building is simply conceived as a ribbon of glass, which forms an envelope in the museum collections. The envelope is an appropriate word Gunnar Birkitz, the architect, and I know from personal experience, is sparked by creative ideas which are sometimes expressed on the back of an envelope or a napkin. And go ahead. I thought you'd be interested in seeing this. This is a church that Gunnar Birkitz did in Columbus, Indiana, same architect that did our museum. Again, the exterior form wraps around the steeple. I think there's another slide on the inside. This is the interior of that church.

[36:15]

Columbus, Indiana, incidentally, has more examples of world-class architecture than any city in the United States. We think of Chicago and New York and maybe not so much Los Angeles. But Columbus, Indiana, a town about the size of Corning, has, oh, 60, 70 examples of some of the best contemporary architecture in the United States. All right? Symbols. And this is in line with what I've been talking about of simply conceived ideas. This is a symbol that I did for a liturgical conference a number of years ago for Tony Ciccarella. It goes way, way back. What I did here And so I just took two lines of different weights and two simple forms representing the universal euphemism, the chalice. In developing the design, I started with a rather representational image and kept taking away things that were not needed and did not contribute to the essence of the symbol.

[37:23]

And that's really how you achieve a very effective symbol, is to make it simple. The next three slides illustrate an openness to different ways to express birds. This is a symbol that I did for the Ithaca Festival, which was an arts festival in Ithaca. And again, trees, birds, and water. But the point I'm trying to make here is this is one way to express birds. Go ahead, John. This is another way. I just took a spiral, just a spiral form, and screened it on the back of a prism. And then you have an owl comes out of that, but a very simple design concept. Another way to treat a bird, an eagle with stars for feathers. This was a symbol that I did for the Horning Bicentennial. I'd just like to show you now, very briefly, some examples of work done in my previous life at Corning.

[38:35]

Again, expressing the idea of simplicity. Here I just took two colors of blue and wrapped it around the fuselage of the aircraft. And in corporate aircraft, you're really not allowed to use any names on the aircraft for security reasons. But you need a very strong, simple way of identifying for air traffic controllers or for people who use these planes. But again, just a very simple way of solving a problem. Same with the interiors. I use three colors for the interior furnishings and the trim. These are examples of scientific instruments using simple wedge-shaped forms, minimal controls and graphics, very clean and very simple. These are pH meters. Go ahead. I really had the privilege of helping to select the architects for all of Corning's major buildings.

[39:46]

among them the corporate headquarters. I provided oversight on all of these projects, and this particular one was done by Kevin Roach. He was the architect at his headquarters, and Kevin was born in Dublin. He studied architecture at the University College in Dublin. I've always admired his work. He is very direct about creative solutions to building design. My favorites are the Ford Foundation, which he did in New York, and all of the ongoing expansions for the projects at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. If you've been in the American Wing, you've been in the sculpture gardens. Kevin has done all of them. I once asked him what he did when he was not designing buildings. His goal is to read all the English novels written in the 19th century. And Kevin's about my age now. He's a little older than I am, I think, right now. OK. Again, the goal here was to integrate the scale of the building and headquarters with the scale of the downtown or Market Street.

[40:59]

And of course, it's heavy use of glass. But again, a very simple approach. The form on the top, some people always ask what that is. a reference to the Robinson ventilators on top of the old glass plants. Okay? Now, I'd like to show you now, reflect the idea again, simplicity and hospitality in designing my own home. And a couple of things inspired me before I designed my own home. Now this is a sketch that I did of the houses in Portofino, Italy. I was attracted to the consistent, simple forms of the houses, and of course to the manner they were sited on the coastline. This housing project is called Sea Ranch. It was designed in 1964 by Charles Moore.

[42:03]

It's along the California coast south of San Francisco. I was taken by its simplicity of the shed roof construction And the site, of course, is very beautiful. You know, the shed roof configuration is really the first example of American architecture. We think of American architecture as really Georgian or Federalist, but the real innate to the United States was the shed roof farm construction houses. I think there's another one there. And this is the site of that. of that project. Now, a little less ambitious, go right ahead. And this is the design of my own house. And again, it reflects the shed roof construction. This is a more recent picture of it. I once read that Henry Moore, the sculptor, had his own house, a design, and he influenced the design of it to a great extent.

[43:06]

And one thing that struck me was that he didn't have any plantings around the base of his house. And his whole idea was to make the house appear as though it had just risen out of the ground. So I stole that idea. And of course, it's less maintenance as well. But that's what I did here. I have no plantings around the base of the house. And I hope it gets that same feeling, OK? And this is just, again, the sighting of the house on a piece of property. It's a very natural environment. Now, you can see the influence of the monastery on my own house. In fact, if you look at the light switches in the monastery, I have the same light switches in my own house. But the simple oak and the period in whiteness is what I was trying to achieve. Just another detail from that how. Okay. Just a few more slides on painting.

[44:09]

Some of the paintings that I've done that express the composition, simplicity in composition. Just one single rowboat. Go ahead. Three rowboats. And again, here, the simplicity of horizontal composition. Three boats align the horizontal of the horizon and one vertical, which is the mast on the boat, OK? Next several slides just, again, reflect the idea of openness of thinking, different ways of expressing the same subject. These slides are window. This is a window that I did on Nantucket a regular traditional house. Window, okay, next. This is a window from the Taos Pueblo. Again, it's a window, but it's done in a different style and a different way. It opens some ideas.

[45:10]

Go ahead. Another window. One day at Chautauqua, I was waiting for a lecture and sitting there, and I noticed this wonderful woman with a head of white hair. And of course, what made it so beautiful was the light coming through the window. And so this is a painting of the inside of a library with another way to express a window. This is a farmhouse window in western Pennsylvania. A very direct way to paint, to express this. One stroke to the plate. I was really working with just a variety of colors, but essentially they're very simple. shapes, four ways to say window. I include this just to demonstrate the simple way I use brush strokes in most of my painting, a very direct way. Go ahead. The taxi is just really a formation of about four or five strokes of paint.

[46:14]

Still life, we get to the detail. Next slide. You can see it's just a very direct, simple way of expressing a form. Another way, this is a park in New Mexico. Go ahead. And here, this is a group of brush strokes, that's all it is, but it's people on a beach. But it's a very simple, direct way of expressing it. Same here with a scene in New York City on a wet day. White stallions. Same thing. Very fast, simple way of expressing it. Three colors, line, and these lemon forms. I'll go through these rather quickly. And then Mount Savior. I've done a number of things on Mount Savior. I'll go ahead.

[47:17]

Next one. This is a little painting done from where Mary Skinner lives. In fact, the hill on Mary Skinner, you can look across the valley to the monastery across the hill. But I want you to notice the fall foliage, and they're just simple brush strokes, no detail, just very directly down. Okay. A number of ways, I said earlier that one of the treasures of Mount Savor are the sheep. And this is an expression of sheep here, just really a white form. And the heads are just in dark shapes and very abstract in a way, but it has a group of sheep. Go ahead. Very similar treatment, another way. Okay? And five strokes, five sheep. Okay? And finally, some of the sheep looking across the meadow.

[48:22]

OK, we can put the lights on now. So in summary, I've really tried to illustrate through a rather eclectic selection of images how I've been influenced by and in turn influenced projects embracing the Benedictine tenets of simplicity and hospitality. The end result of all this, I hope, is the creation of beauty. Jared Manley Hopkins states that, quote, beauty it may be is the meat of lines or careful space sequences of sound. These rather are the art where beauty shines, the temperate soil where only her flower is found, unquote. I believe expressions of beauty and simplicity awaken us to the holy. So stand still, be open to beauty. Never lose an opportunity of seeing anything that is beautiful, for beauty is God's handwriting.

[49:31]

Finally, I give thanks for the shining moments of life that the prism of Benedictine spirituality has provided for all of us. And I shall be forever grateful for the gift of Mount Savior and the members of its community. May God's grace be with you for the next 50 years. Thank you. Do you have any questions or additions or subtractions? Alexander Jones, who translated a French Mouve de Rouge into English, said from the beginning that truth goes in beauty where it doesn't go at all. Martin, you could probably speak to that.

[50:42]

The library of Montecassino. She had asked if she was correct in thinking there was a wonderful library in the monastery of Montecassino. I've never been to that. Yet most of the Venet monasteries in Europe of that age have wonderful libraries. Our own country, St. John's, of course, the same, and nowadays with the, what's the, microfiche, for one thing, and then, of course, the present ways of copying things. But some of our own libraries in this country have all those very useful, you know, but, you know, both of them. But the monasteries in Europe, though, Yes. Ronchamp, yes. Concrete, yes. So it was very leading edge in the engineering and construction of it at that time.

[51:49]

Corbusier, of course, worked primarily in concrete, reinforced concrete. At that time, it was described as brutalism. And I didn't show you a monastery that was really brutalism, not my favorite. Very geometric, very hard. This, to me, was a much more successful monastery that he did. But it was all concrete. Yeah, it was painted concrete and the roof is painted concrete. That's right, yeah. But it's a marvelous building. It's in a small town and the approach to it, you see this gleaming small white edifice at the top of the hill. It's really something, yeah. Yes? Yes. Well, you know, I didn't include his name here because I didn't think it would mean anything to anybody. But I should have. Yes. Yes, yes.

[53:02]

Dissenters. It could be. It could be. I'm not sure. Yeah, it could be. Yes. Yes, Frank. I wonder, maybe an oversimplification about art, that the 12th and the 2nd catenaries were old and classical. No, we'll get back to that. It's an oversimplification. Let me talk about complexity. Is that essentially more classical than world? Yeah. Yeah. Classical architecture is very simple, very austere. Think of the Greek temples, very simple ideas, horizontals and verticals.

[54:03]

So I consider that a very simple, direct approach to things. Baroque, of course, would be a great deal of embellishment. And as I said earlier, there was a great conflict in the Middle Ages about whether monks should be in that environment. But on the other hand, there were a lot of political influences, a lot of patrons who wanted to... There's probably a lot of competition between churches within various cities and villages as well, but I don't consider Baroque a simple and direct approach. I have a follow up question on that. I'm wondering what the issue looks to by where we stand. It seems to me that the bicycle is where we stand stability, maybe, but that's what it is. Where the road represents something robust and right beside you. Yes, yes. Out of control. Yes, yes, sure. So the cycle, yes.

[55:06]

Yeah, they all have psychological components of them, whatever the visual expression is. We think of banks, we think of classical buildings, we think of federal monuments in a classical way. We think of corporate headquarters in different ways. Way in the back. What should I do with all the work of all the bandits out there? No, I don't question it. It's just one of them. A lot of bandits, they are an example of lying, giving lies to humanity. They've always done the craziest stuff. Bargaining with people about the law, or anything. Well, it's a whole thing. You don't know that. You mean romantic landscape painting? Yeah.

[56:12]

Well, again, I preface the talk with this is the formation of my own aesthetic. And I have tied that into the Benedictine idea of austerity and simplicity. So I wouldn't consider that in the reference I'm using. as simplicity, when you talk about romantic landscape painting. Although, you know, if you get to the essence of some of these romantic landscape paintings, you get to the basic composition, some of them are very simple. You take away all the detail. Academic painters try to express every little detail. But if you took away all that detail and you stripped it to its basic composition, some are more simple than others. But it doesn't speak to the point that I was trying to make with my own aesthetic, no. Yes?

[57:14]

Could you address the paradox that, in light of what you've spoken about here, that the primary criticism against modern architecture in striving for simplicity was that it was terribly infested. And in a sense, that was its fatal flaw. Well, architects were enamored with new materials, whether you could work with concrete this way. They were enamored with the construction methods of of glass, reinforced concrete, and I think in many cases architects were not really designing for the people who were to use these buildings. And they still are, in some cases. And that, I think, is the reason for the very human criticism about the coldness of buildings.

[58:19]

Why I didn't show you the Corbusier Monastery? It looks like a prison. But it's interesting. You know, we're doing the museum, the new museum, Corning. And I looked at the plans for the auditorium. I think I talked to you about this. And that new museum, technically, is incredible, the way that the glass is hung, the way the glass is joined. And then the theater was going to be done in that same way, with a lot of steel and glass inside the theater. And my feeling was not a human expression. The theater should be a warm place. in contrast to the very severe structure itself. So we put a lot of wood in there. So I think architects have compensated for some of that by the use of warm stone, wood, things of that nature. But you're right. It was criticized originally because it was so severe and so brutal, not human.

[59:21]

And I don't mean austerity and simplicity to be inhuman at all. I think you can do that. without being so severe. Let me just look at the room we're in right here. It's very clean, very simple, but it's still warm. He's approaching, trying to keep some of this to be, let's say, ornament less, finer. They go more for ornament. He didn't even have a lot of trouble at it. The spout, the water spout, it was the foundation of ornament, but it became ornament. Well, it was stained glass also, stained glass. Whether they want to achieve publicity or not, there's a cycle where they achieve publicity and then they go back to the buying movement, where they become a part of things. And then they go back to painting some books. It's a complete cycle. You can't get away from it.

[60:22]

Well, the crypt downstairs here, the crypt is concrete, stone, but you have the warmth of those small stained glass windows. One more? Yes. Those are oil paintings. Those are oil paintings, yeah. And I use very wide brushes, big brushes. All right, thank you. Thank you very much. That's it? Oh, thank you.

[61:09]

@Transcribed_v004

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ