You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Suffering as a Path to Enlightenment

The talk explores the idea that suffering is the key to spiritual awakening, supported by the Zen teaching of "the more abundant the clay, the bigger the Buddha," suggesting that adversity provides the opportunity for enlightenment. It compares how different Buddhist traditions have approached enlightenment, and how Zen incorporates elements from other philosophies, such as Taoism, to form its unique view on how suffering and personal afflictions can foster wisdom and compassion. The discussion emphasizes the Four Noble Truths, particularly focusing on "nirodha" or containment, as a method of addressing suffering. Zazen practice is highlighted as a means to cultivate openness and manage suffering constructively.

Referenced Works:

- "Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind" by Shunryu Suzuki

-

The book is referenced in relation to managing passion and suffering through the concept of providing a "big field," aligning with the practice of Zazen to offer space around afflictions.

-

Four Noble Truths (Buddhist Text)

-

Central to the talk, these truths outline the nature of suffering, its origin (samudaya), its cessation (nirodha), and the path to cessation, forming the structure for understanding suffering and its role in spiritual growth.

-

"Shōbōgenzō" by Dogen Zenji

-

Mentioned in context with Buddhist teachings that articulate Dogen's insights, it underscores the transformation of suffering into enlightenment, forming a grounding narrative of Zen philosophy.

-

"City Center" and "Zazen" Practices

- Referenced as real-world applications of Zen principles, these practices embody the teachings of containment and openness as ways to engage with and transform suffering.

AI Suggested Title: Suffering as a Path to Enlightenment

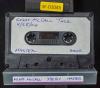

Side: A

Speaker: Kosho McCall

Location: ZMC

Possible Title: Talk

Additional text: MASTER

@AI-Vision_v003

Let me know if there's anything behind me, okay? My name is Kosho and I'm a monk who lives in this valley. And I wanted to talk about one of the little golden nuggets that's buried in our particular tradition. And the... particularly in the Japanese school, whose lineage I'm in and that most of us are acquainted with. And the founder of that school in Japan was a guy called Eihei, named after his monastery, Dogen. I think his real name was Koso Dogen. Koso Dogen Kigen, or something like that. But one of the things that he said really, let's see, a couple of years ago, really struck me as bizarre.

[01:10]

Well, actually, most of the things he says strike me as bizarre. But this one in particular struck Some of you have heard me talk about this before. But the expression he used was, the more abundant the clay, the bigger the Buddha. And... when you think about it, the more abundant the clay, the bigger the Buddha. Clay isn't something that you really, if you're going to make something lasting or important, you usually don't use clay. Even if you fire it, it breaks easily. So what struck me was, clay is kind of inferior when you're thinking of making Buddhas. And what is the background of his saying that? If I don't mention that again, will somebody remind me that I forgot? The background of that is that in the first school, well, not the first school, but the school that was sanctioned by the government in India, the Theravadan school, if you asked one of them, one of the monks, what they wanted to be when they grow up, they would say, I want to be an arhat.

[02:28]

I want to get rid of all my afflictions. And later on, during that time and beyond, there was another school forming and growing too, the Mahayana, of which we're a part, the larger vehicle. We call ourselves the larger vehicle. We call them the smaller vehicle. And if you asked, the Mahayana school really flourished in the first century. of this era. And if you asked one of those monks what they wanted to be when they grow up, they'd say, I want to be a Buddha. You wouldn't hear that before the first century too much. Nobody could be a Buddha except the Buddha. And it takes a Buddha to become a Buddha eons, apparently. So obviously something happened. And So when Buddhism entered China, like it does with any culture, it became affected by that culture, the culture of China.

[03:43]

And China at the time was apparently, oh please, anything I say, know that this is only my understanding. Truth or falsehood has nothing to do with any of it. But from what I understand, the primary religious culture of China at the time was Taoism and in terms of society, polity, Confucianism. And when Buddhism came from India into China, it became Zen because of the influence of Taoism primarily. So, things that came to us from Taoism are the love of nature and appreciation of nature, the balancing of opposites, yin and yang, that sort of thing, and the notion of something called buddhata, buddhata, which we translate as Buddha nature.

[04:45]

that not only are we called to deal with our afflictions, but we also have the chance to realize our own Buddha nature, that we are Buddha. You'll hear that a lot from us, that you are Buddha. And I wonder if Buddha would have thought of that. Well, there's no way of knowing, is there? So the one would want to become a bodhisattva, which means an awakened being. And what do awakens being? They live for the benefit of others. Not in a martyr sense at all. Bodhisattvas aren't Western, particularly. There's no sense of martyrdom attached to living for others and serving others. It's serving others just because that's what we do. Another quality of Buddha nature is that it's compassionate. It is compassion, that it's kind, that it's generous, and that it has its own wisdom.

[05:48]

And, of course, it has its own wisdom because wisdom only comes from the inside. It doesn't come from the outside. We know that, right? And wisdom comes from dealing with one's own affliction, not by blaming others for it, but by actually feeling what we're feeling and actually facing our own suffering. So when Dogen says, the more abundant the clay, the bigger the Buddha, what he's talking about is the more suffering you have, the bigger the Buddha you're going to be, or the bigger the Buddha you are, if you develop a certain point of view towards it. So we have an expression that we use. In practice periods, we eat most of our meals in the Zen Dome. It's very formal. It takes a long time. We actually eat for about seven minutes or something.

[06:51]

But the whole ceremony takes about 40 minutes or so, if we're lucky. And a lot of the time is chanting certain things. And the thing we chant at the end, I was trying to remember it. Abiding in this ephemeral world, like a lotus in muddy water, the mind is pure and goes beyond. Thus we bow to Buddha. So that expression, like a lotus in muddy water, you'd think there was some sort of design flaw in lotuses, that they would have to, that they flourish in muddy water, that they flourish in the muck and the mud, right? I mean, other things grow in, you know, earth, grass, trees, but mud at any rate, mud. So it's not an accident that a lotus grows in mud. It's not like it could grow better if it were on a hillside with plenty of sun and not the possibility of being drowned by water.

[08:01]

In fact, lotuses don't grow. in meadows and hillsides, they only grow in swamps, in mire and muck. Isn't that cool? And so do we. So do we. And lest you misunderstand me, it's not like we have to go out looking for suffering. We have plenty. And a lotus, as you know, is the symbol for enlightenment, for our highest aspiration as human beings, our Buddha nature. And so when he says that the more abundant the clay, the bigger the Buddha, what he's saying is that suffering itself is where awakening happens. Awakening doesn't happen when things are fine or when you're peaceful or when you're happy or when everything's going my way.

[09:03]

It only happens in the midst of suffering and nowhere else. When I read this I was really shocked. I didn't think it was supposed to be this way. That did sound like a flaw of some kind. Why must suffering, why must awakening only come from suffering? Well, I don't know, but it does. So suffering, one of the translations for suffering is from dukkha. Dukkha is the Sanskrit word. And it means a feeling of dis-ease, being ill at ease, unsatisfied, that something's wrong. It can be very subtle like that. You know what I mean? The worst form is sort of that low-level anxiety when you don't even know what it is. In fact, the definition for anxiety is you don't know what the cause is.

[10:06]

So it goes from very subtle suffering to major suffering, and the Buddha listed many. Getting what we don't want, losing what we do want, death, birth, old age, Although some of us carry it well, I think. Well, old age, sickness, and death together make an unhappy bunch. What else? Grief. No, I forget the words. But you can see, so not only is it mental anguish, but it's also physical things that happen, any event that causes affliction, suffering. We'd rather be somewhere else. Any of those things. In fact, a good diagnosis for suffering is, get me out of here. You ever have those moments? Get me out of here.

[11:11]

So, and... We have our own ways of dealing with suffering. And since none of them work, I think that's why a lot of us gravitate to a place like this to find a way that actually does help. Things we try to do are either blaming is a good one that doesn't work. But if I'm feeling really bad and I can see that it's your fault, that makes me somehow feel better slightly. But it doesn't last too long because I still feel that way. No matter how much I blame, I still feel rotten. Or we can develop a story about our suffering to explain it, to rationalize it. You know, I'm like this because of this, [...] and this. And that story becomes so hardened And so it becomes sort of legendary, our own myth, and it solves nothing.

[12:18]

It just becomes a big heavy weight. Or we can try to avoid any occasion of suffering, aversion, to run away from it, to try to not be there when it happens. That doesn't work either. Because, as you know, from living together just a short while in the community, it finds you. It knows your name. It can smell you coming. Or we can attack it and try to kill it, try to get rid of it, to crush it, to dominate it, which only, of course, fuels it. It loves the power that fighting against it gives it. So, and especially, there's one other thing I wanted to say about that. Our culture is very puritanical. I'm from Maine, the Northeast, and I didn't realize that I was a Puritan until I got to California.

[13:25]

and started listening to people, how they're kind of like soft and, you know, these are the ones that I've met and liked. They were soft and open and forgiving and caring and, oh, just so nice. And at least the people that I hung around with in the East Coast weren't like that at all, kind of hard and cold and sharp. I remember going back, I was out here for several years and then went back and spent some time in a Christian monastery in upstate New York. And we had an influx of guests from New York City. And we took care of them. And I was watching them and thought, oh my God, what's happened to these people? Are they all like that? Because they were very, you know, the way I was. Yeah. Oh, so pure tannical. Puritanism gets a lot of its understanding from way back, from Greek philosophy, where there was a duality of body and mind, body and spirit.

[14:43]

So that from one certain point of view, spirit was good, the high, the highest, the ideal. And body was the thing that corrupted the spirit. So the body was really bad and nasty and awful. And the body was usually the cause of a lot of passion. And passion was to be avoided, because passion's bad, because it leads to excitement and loss of control. Any of you know? Any of you familiar with that? Okay. So the puritanical approach was to stop it at every point, to fight it. Most effectively was burning it out of people, setting fire to them. Even the church, too. The church had that during a certain period. So, obviously, that didn't really work. It was very temporary. fix so I was delighted to find from our tradition that there were other ways to deal with the passions the afflictions and

[16:01]

Oh, so, let's see. Suzuki Roshi, who is our compassionate founder, who founded Zen Center, wrote a book that probably most of you have seen, Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind, most of which I find very difficult. But there's one place he talks about control. Remember that? Where he talks about, I'm not sure I remember it all, but he talks about how to train animals or how to control animals. And you do that by giving them a big field. Common sense would say, well, you put them in a box. Then you have control over them. But the trouble is that that always backfires, and they get very unhappy and die. Like us, just like us, if we try to do that to ourselves. So if you give something that's uncontrollable, just because it's alive, like anything that is alive is uncontrollable by us, then if you give it a big field, then you have some control over it. Does that make sense?

[17:05]

I understand children are like this sort of, too. Have any of you tried dealing with them? Well, the Buddha wanted to find out what the hell is going on He had a happy life, apparently, a palace life, where all of his needs were looked after, a life of abundance and privilege. And he wondered why he was still slightly unhappy. And then he went outside the palace, as you know, and saw old age, sickness, and death. which weren't supposed to happen. It wasn't supposed to be that way, that those things would happen to even him. But when he found out that they actually were going to, then he decided to get to the root of it and how to be free, how to be free of affliction or its effects. And so what he found were what he called the Four Noble Truths.

[18:10]

And just briefly... The first one is that, guess what? There is suffering. It's real. You can't hide from it. You can't paint it a different color so that it's not the same. You can't pretend it's not there. But it actually is a human event. Why? It doesn't really matter so much. Like, why do you die? Well, because you live. So it's not really something wrong has happened. It's just that these things happen. So how does one manage the uncontrollable, the unpleasant, with grace? With grace. And so what he noticed was, he noticed affliction, and then he noticed that something immediately comes with it. And that is samudaya. He called it samudaya.

[19:11]

The first one dukkha. The second noble truth is samudaya, which is like what I think of as amoeba. Everybody know what amoebas are? Amoebas. One-celled. Very tiny. Very tiny. In a microscope, they're very big, though. And when you look at them in a microscope, you can see how they work. And apparently, they don't have much of a brain, hardly any cerebral cortex as far as I can see. So they're very natural. the way they act. If they come up to something that is harmful, very intricately designed, they can tell if something's harmful just by coming near it. Then if it's harmful or nasty, dangerous, then they immediately, automatically, without any thought apparently, although I couldn't swear to that, they withdraw.

[20:12]

They withdraw from it. If it's something they come up against that's tasty or beneficial or food, then they'll engulf it and the food will become them. They'll digest it. If it's something that is neither of those, they'll just sort of move on around it. We're exactly the same if we don't interfere too much. Oh, no, actually, whether we interfere or not doesn't make any difference. But Samudaya, the second noble truth, is what happens automatically in us. If something is painful or looks like it might be, we will have a response to it. It's automatic and out of our control. Think of it, you know? You know, a hot stove? You don't have to think about removing your finger. It's automatic. But of course we have higher realms, too, of intellect.

[21:14]

And then things get complicated. So that immediate response is what we call feeling, samudaya. Oh, no, vedana. It's automatic. It's automatic. And there's nothing we can do about it. And since there's nothing we can do about it, then it's worthy of respect. And that's why it's called noble, just like dukkha. There's nothing we can do about it. These things happen. And since it's not in our control, then we better be respectful of it. And so it's called noble. All right. So there's that immediate response. And then there's something that, then the third noble truth is what we can do with it, what we can do about suffering. And that is called nirodha. And nirodha is variously translated. The usual one is there's an end of suffering. End. I never found that helpful. What do you mean, end? What I was much more interested in is how, or what do you do?

[22:23]

And so it's translated in There are different translations of that word, Neroda. And let's see, there's a modern... Actually, these people are all alive. One are some people in England, the Braziers, who are therapists and also Buddhist clergy, husband and wife, who translate it as... as... Containment. That's what I said. Yes. Link, thanks. Containment. There's a contemporary Japanese master whose name is Nishijima Roshi, who is also the translator of the Shobo Genzo and the Four Volumes, which I find impossible to read myself as an aside. Very dense. But as a teacher, as a lecturer, he's really quite fascinating because he uses a lot. He finds Western psychology very fascinating and helpful. And... And so he translated it as self-regulation or self-restriction.

[23:30]

And that's the same thing as Suzuki Roshi's giving it room, in other words. And one expression we use around here is not leaking, not leaking. An example of leaking would be something a person has just done, either in their behavior or a word or even a look on the face, and it causes something inside of me to react. To leak would be to try to make them stop it. or to blame them, or to somehow make it their problem. If only they would stop, I would be a much happier person. And that's really, I mean, that seems to make common sense, but in terms of reality, it's full of beans. So not leaking or containing the affliction or self-restricting the affliction is to keep it, to not leak it, and to actually study it, if you can stand it.

[24:39]

I remember so many years here with one of the practice leaders and I'd come in to see them and I'd be having a fit and she would just say, can you stand what you're feeling? Can you just stand to feel what you're feeling? And my response for quite a long, long time was no. Of course I can't. It's painful or makes me anxious or makes me mad. Of course, anger usually comes from hurt. It's a secondary emotion. So can you stand your own hurting? And usually not, don't you think? Usually not. We'll usually try many things to get out of it. One is the story business that I talked about before. Another is to... Sorry, my mind keeps going blank. I don't know. I think it has something to do with the, what's that thing called we were using today?

[25:43]

That gun, that screw gun. Impact driver. Having that much power. That was so great. Yeah, feeling what you're feeling. Incidentally, for those of you who are interested in these things, there are only two things that are unconditioned. Only two things. Everything else is conditioned. The first one is space, empty space. The other thing is Naroda. when we decide not to leak, when we decide not to release our discomfort or our affliction outside ourselves. Isn't that interesting? But that's not conditioned. That's an actual Buddha choice. It's the Buddha in us acting. I wanted to give one example of... of this kind of thing.

[26:48]

I was away for three months, the last three months, and part of that was at a conference and the other part was doing a long ceremony. But one of the most significant things that happened was I discovered the Internet. I'd never seen it before. It's amazing, isn't it? Anything you want to know is right there. Well, for most people. I had help. But one of the things I wanted to find out about more was some of the personality disorders so that I could understand most of my friends here. One of the unsettling things was that I found I could relate to them too well, because I could see myself in a lot of these symptoms, which was actually very helpful.

[27:49]

Horribly humbling. In fact, I read one of them, tried to read it on a plane, a five-hour plane trip, and I found it almost impossible to read. It was so painful. Such is the nature of our conditioning. And by that I mean, conditioning is kind of a light word. It sounds so tame, doesn't it? conditioning, like air conditioning. It sounds so easy and fluffy. But I think in terms of ego, of the self that we construct, this is who I am, and that's who I'm not. This is me, and that isn't. or you aren't. That kind of firm, solid separateness that gives such a sense of security, safety, unless rattled. It's not only just conditioning. Our behavior becomes habitual, a habit.

[28:51]

For example, there's a disorder, which is kind of a misnomer for all these things because they're not really disordered, they're very ordered and very structured. and very dependable and predictable. One of them is social anxiety disorder, which they said, the people who have investigated this thoroughly, apparently, said that it's not talked about much, and they suspect that a third of the population suffers from it. And what it is, is coming into a room of a lot of people like this, or worse, a room of strangers, or meeting one stranger, or worse, one or more strangers. And how it manifests is in an increase in panic, anxiety. And depending on how strong it is, the symptoms get stronger. In fact, they may even become even more physical and you become sick.

[29:54]

And I was so delighted to see this because, good God, it's so nice having what you suffer from have a name. Otherwise, you think it's you. That's you instead of just some conditioning. And so it describes some things. So when you come into a room of strangers, for example, and you get all scared, and you're the only one, and you know they're all looking at you. You think that because you can't look at them because you know they're looking at you. And not only that, but they're judging you. to see what kind of person you are, how you act, if you say the right thing, or if you're stupid, if you say the wrong thing. And of course the anxiety just goes through the ceiling. So some of the ways of So if that happens once, it's guaranteed it's going to happen again. And when you're in the situation again and you react the same way, the conditioning is stronger.

[30:59]

It's reinforced so that it becomes a habit. So that when I would walk into a room like this, I would automatically be there. I wouldn't even have to think that everybody was looking at me and hating me and judging me or liking me. You know what I mean? That kind of stuff. And every time that would happen, it would get stronger and stronger. Yes. And so there are things you can do about that, obviously. One is to actually try to watch what's happening, what's actually happening, and to think that not only you feel this way, but probably everybody in the room does. Like a cocktail party, what could be worse? Or having to drink in order to go to a cocktail party. Doesn't anybody do that? So not only do things become habit in terms of behavior, but they become addictive.

[32:04]

And one of the biggest addictions is ego, is self. We'll do anything to preserve it. We'll do anything to defend it, no matter what, usually. And that's a pretty good description of an addiction. We'll go anywhere, do anything to preserve that sense of self. And it doesn't matter whether it's an inflated sense of self or a deflated sense of self. They're both the same. And one of the things I think you could say about the Buddha was that he was trying to show us just how hard it is, just how hard it is to awaken to reality. Because with all the addictive behavior, habitual behavior, which is so difficult, it's really hard to know what's actually happening. Does that make sense? Yes. Like if you have social anxiety disorder, you walk into a room, you can't tell what's happening, what's really happening. It's even hard to talk to people because you've got this whole bunch of stuff, which we think is me, in between us and what's going on.

[33:13]

So as far as I can tell, Buddhism isn't quite so much about religion or philosophy. I think it's more about dealing with reality, discovering reality. which you wouldn't think would be that hard, because what else is there that's so difficult to see? One more example. A friend of mine at City Center told me she didn't know I have a problem with crowds. And she said, I'm going to a meeting in a week. It's a meeting of a group of San Francisco's biggest philanthropists. And they meet, just about 20 of them, and they meet to discuss spiritual issues. And they're having this special guy who's a Jesuit. And from my background, when you hear Jesuits, like, run for your life.

[34:16]

Who's a psychologist, which is even scarier. And do you want to come? And I said, sure. I think because I knew what the problem was. I knew that my suffering was legitimate in a false sense, in a false kind of way. Plus, a lot of things had been happening during this three-week ceremony I was doing at the city. So I went. And I could feel, when the elevator came up, I could feel it happening, starting to get tight and trying to pull in the defenses and gather the troops, circle the wagons. Excuse me. But I also found that something else stronger inside of me said, this isn't necessary. This really isn't necessary. And so I took a deep breath and went into the room and there were people there, sure enough. But I could see them as really nice people, wealthy people, but nice people who were kind.

[35:27]

And then the Jesuit came, sat down, and we introduced ourselves, which wasn't as bad as you might think. We have something called check-in at most of our meetings, to which most people would rather be absent, I think. That's the impression I get. That's where you say a little something about yourself in front of all these people. So that's what we did, and that was okay. It felt okay. And then he started talking, and I noticed how complicated some of the theories he was running out were. You know, the usual typical psychological theories about human behavior. And I was thinking how, geez, God, if he could just come be with us for a week or so, he could see how much simpler things are than that. And so at the end, one of the things in my book of rules is never speak to strangers. And even with that, I went up to him at the end and said, wow.

[36:32]

I told him who I was and what I did and all and said, boy, you know, I've been studying the psychological stuff and I was a therapist for a while and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And we got along just right. It was just wonderful. And, in fact, I invited him to come visit City Center, which he did, which I called up and invited him, and he came. And then he came, and we had some tea and talked for two and a half hours. I didn't even notice the passage of time. And then at the end he said, you'll have to come over to the Jesuit community for supper. And I thought... I said... Oh, yeah, I'd like that. And I did. I did like it. So, nirodha. So giving the anxiety, giving the suffering some room, and not just doing the automatic response, the automatic leaking. And that seems to work for any passion.

[37:35]

And it's not easy. That's all I have to say. We have 15 minutes. I'd like to hear your views. Three. Did you hear of the 20 commandments? Did you see that in Monty Python? Moses came down with 20 commandments. No? 15. Fifteen. Fifteen commandments. You dropped it? Ten commandments. No. Yeah, the fourth commandment, the fourth noble truth is the Eightfold Path, which in one way of looking at it is what develops when you practice nirodha.

[38:37]

You can't help but walk the way a Buddha walks or act the way a Buddha acts. Plus they can also be used to encourage nirodha. What's nirodha again? Nirodha is a containment, not leaking. Not leaking the reaction from the suffering. Not making it worse. It's like a passion arises and you want to go do something about it, but you don't. You wait and you study it and see what actually is happening. It's like falling in love. if any of you have any experience with that. It's not very trustworthy, have you noticed? Which exactly isn't trustworthy? Falling in love. In terms of how you view the other person. You get this picture of the other person and they're wonderful, gosh. In fact, you see them as even more than a Buddha. And logic jumps in to serve passion.

[39:42]

Have you ever noticed that? we can rationalize through flawless, ridiculous logic. Anything. Anything can be rationalized. So passion is our life, and it's part of life, being alive. Not so trustworthy if we just react to it. I'm curious about not losing the opposite of anxiety or Oh yeah, that's an affliction. Buddha said joy, too much joy can be an affliction. Because you want to keep it. You want to keep it. In fact, you'll do anything to keep it. Try to recreate it over and over again, and it's never the same. So that actually the attempt to recreate it becomes an addiction. which leads to it burning out and then it demands more of the technique.

[40:44]

It's awful. Jeremy? I think you said once one learns how passion can help practice is quite beneficial. That's what I got in my head. Maybe you could get into that. Once one does what? How can passion be something that benefits us in our practice? It's not a benefit. It's the core. No, it's the core of our practice. I think. That's my opinion. It's the core of our practice. Well, because it's always there and you can't get away from it. And it's the only thing that bodhi mind comes from. Awakening. Does that make sense? You're like, what's to awake from? Awakening only comes from affliction, passion. Passion is kind of an old-fashioned word for affliction. Suffering. Is that why Mel Gibson did the movie?

[41:47]

Really? Well, it's called the passion. It's called the passion. Jesus' passion. It refers to an affliction, not an enthusiasm. Well, not that. That was a rather painful passion. Some of them are very pleasant. The New York Times had a good article on why Mel Gibson had such a good time with that passion. What's the difference between an affliction that's a passion and an affliction that's a painful one? You spoke of the amoeba being averse to that which is harmful for us and, you know, engulfing that which is good for it. But we as people tend to, or at least have a tendency to engulf that which is bad for us and be averse to that which is good. Amoeba seems to have it on us a little bit. Yeah, amoeba, well, amoeba doesn't have the cerebral cortex. That gets deluded into thinking that something that's actually destructive is pleasant.

[42:50]

I'm familiar with that myself. Can I follow up just for a second? I'm sorry. One more thing. Any addiction, we usually get addicted to something to change our moods. Joy changes our mood. It's a nice mood change, so we try to keep it. Substance abuse, same thing. It has such promise. Such promise. And it was so cool and exciting the first time. My follow-up was, I understand the logic in pursuing a course that would somehow free you from suffering, but I don't understand the logic of a course that would free you from pleasure. Oh. I wouldn't say that. I would say passion. I would say affliction, free from our reaction to affliction. I guess very complicated and messy, but needn't, I think. For example, gosh, listen to the creek.

[43:55]

Isn't that pleasant, isn't it? from a certain point of view. I had a friend from New York City come and stay here, stayed in one of the stone rooms, and he said the next morning it was like trying to sleep with a continually flushing toilet. But no, we have sense pleasures. You know, we have senses. That's the way we connect with our environment inside and outside. Not that there is such a distinction, but conventionally there is. Yes, I mean, sights are pleasant, pleasing, or unpleasing, or we don't notice. So I think this is freedom from suffering in terms of, let's see, I guess the only way to say it is to say something that Uchiyama Roshi said, which was he asked his teacher, Kodo Sawaki Roshi, what he was supposed to get from Zazen, which was really the wrong thing to ask Kodo Sawaki Roshi, because Kodo Sawaki Roshi said, nothing, nothing.

[45:09]

You get nothing from Zazen. It's not an object to be used for your pleasure or for your better sense of self. Your character doesn't really go away, but what Zazen does is it actually opens the field around it. What? It opens the field around it so that there is more to you than this particular thing that you think is you. Does that make sense? And that, in a way, is an end of suffering. It's not like old age goes away, but my attitude towards it can change. And in that attitude changing, I am changed. So zazen is the practice of opening up. I think giving space, giving space, in fact, practicing unconditioned nirodha, that sort of... We also call it letting go, which I find a very difficult term. Is it?

[46:09]

Is there anything that passes through your mind perhaps on a daily basis that you use to keep yourself in tune to the notion of remaining expansive and open? And, you know, is that something, the opportunity to extend and come up over and over and over again? Is there a catchphrase or a way of... For me personally? Nah. No. No. If you practice zazen, there will be a part of you that knows this. If you do it enough, it takes a long time. A long time. But if you do it, I don't know how much it takes, but in AA they have a saying that as long as it took you to get in the woods, it takes you to get out. It takes a long time.

[47:17]

So actually, at least what I experience is that the usual stuff will come up, but it's so small. It's very convincing. It tries to convince, but it just doesn't have the weight it did because it's not so big. There's just more space around it. I wanted to ask if you could tell us a little bit more about the unconditioned nature, and you wrote that because it's space, don't you see, it doesn't come up well, just space. So how would you, can you say something about that? You know, that's a hard question. I was thinking about that tonight, actually. How am I... How would I say this? How could I? Can I? Because Zazen is developing a habit.

[48:18]

Developing a wholesome habit. I don't think I can. I don't think it matters, does it? Does it really matter? Like, would this affect the soup? Ultimately, yes. Ultimately, nothing that you say matters. But conventionally, it doesn't. Okay, okay. Then take this. My conditioned nature forms our self, myself, my small self, my ego, who I think I am, who I think I should be, whom I want to be. And whenever I act outside of that, it's not in that conditioning.

[49:22]

It's part of my unconditioned nature, which is the Buddha nature. How's that? So if you say then everything is already controlled? Of course. I mean, from a conventional point of view, everything's a mess. But from the unconditioned point of view, everything is absolutely perfect and fitting. It's like the stupid thing of Buddhism, to me, seems to be about exploring reality. Like, what else is there? Do you know what I mean? That seems so clear, doesn't it? I mean, what else could there be? But then when you think about it, oh, lots, lots of stuff. Like, I could think you're thinking such and such and such and such. You know, and I could be pretty sure of that. Totally fabricated.

[50:27]

So that our fabrications and our delusion, they do kind of exist in a nasty sort of way in reality, but they're not reality. Reality is much bigger, right? You are not it, it actually is you. Facing a jewel mirror, form an image. What? Behold each other, you are not it, it actually is you. So we actually are reality. Reality. Reality is us. We are not reality. See? See? It's awful. And I think you do that by spreading the delusion out so that you see less and less of what actually is happening. And in an Now your options are open.

[51:31]

Yes. There's a clearer chance to make an appropriate response. It's in accord, like Galen was talking about the other night, it's in accord with what's happening. But don't get confused. In an absolute sense, nothing is happening. Ever. Do you think that we contain? We contain what? Do you think that we actually do this? You said that we... Something that I do? Is that a trick question? Dude, is it something we do? It's like Zazen, no. Certainly not. It's like saying, okay, now I'm going to be real. From a certain point of view, it's a meaningless statement. But from a conventional point of view, if I don't do it, who's going to? If I don't drive the mushrooms, who's going to? So we live in, like Galen was talking about again, talking about paradox, we live in both, in both worlds, the conventional and the absolute.

[52:41]

And the thing to do is to practice with that, using Zazen as the primary tool, to live in them both with grace. Because they're both true from a certain point of view. It's time. How about we talk about it later? Thank you. Thank you very much.

[53:08]

@Transcribed_UNK

@Text_v005

@Score_85.94