You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Benedictine Prayer: Heartbeat of Community

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk centers around the role of Benedictine monastic prayer as a vital contribution to the Church and society, emphasizing the historical, spiritual, and communal significance of liturgical prayer in the Benedictine tradition. Through anecdotes and historical insights, the discussion explores the impact of prayer on personal spirituality, community identity, and broader Church engagement, highlighting the unique position of monastic communities as guides for spiritual seekers both within and outside the Church.

-

St. Benedict's Rule: The foundational guide for Benedictine monastic life, which emphasizes prayer and community living as pathways to live a well-intended life.

-

Sayings of the Desert Fathers: A collection of early monastic wisdom, including teachings from Abba Anthony on the necessity of personal effort in prayer.

-

Annie Dillard's "For the Time Being": Provides a modern perspective on spirituality and human existence, emphasizing the persistence of divine presence amid life’s material chaos.

-

Rabbi Nachman's Story: Illustrates the Jewish tradition's insight that God also engages in prayer, adding depth to the understanding of prayer in human-divine relationships.

-

Karl Rahner's Concept of Self-Transcendence: Highlights the human drive for transcendence without clear satisfaction, informing the meaning and pursuit of prayer.

-

Ernest Becker's "The Denial of Death": Discusses the psychological need to ignore human mortality in order to function, contrasted with the role of prayer in confronting existential realities.

-

Vatican Council Documents on Liturgy: Establish formal monastic prayer as the central ministry of Benedictine life, underscoring its spiritual significance beyond utilitarian value.

-

Scriptural Influence: The use of biblical texts as a core part of monastic prayer, shaping the contemplative spirituality and community identity within Benedictine traditions.

AI Suggested Title: Benedictine Prayer: Heartbeat of Community

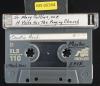

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

Speaker: Sr. Mary Collins, OSB

Location: Mt. Saviour Chapel

Possible Title: A Voice for the Praying Church

Additional Text: 11 Mar 2001, 4:30 p.m. Sunday, Master, SAVE

Speaker: Sr. Mary Collins, OSB

Location: Mt. Saviour Chapel

Possible Title: Question Period.

Additional Text: 11 Mar 2001, 4:30 p.m. Sunday, Master, SAVE

@AI-Vision_v002

I'd like to thank Father Martin and the community for inviting me to be part of the celebration that they are having throughout this year. So it's fitting, I think, to begin this evening's activities. by adding my voice to the many voices that will be speaking words of gratitude and congratulations to these Benedictine brothers of Mount Savior Monastery this year. The brothers stand among us as witnesses to God's faithfulness. In these New York fields, the brothers have made visible, day in and day out, for half a century, the wisdom of St. Benedict's teaching about what it means to live well, whatever one's times and circumstances. The world has been changing around them for 50 years, and they have shown you, their friends, the wisdom of honoring place, honoring tradition, and honoring commitments to one another.

[01:05]

as the way to flourish from one generation to the next. So their very existence among us, I think, is a contribution of monasticism to the church and the world. And I think it's evidenced by the fact that so many of you have found your way to their home and their chapel. Then my word of congratulations to you, scattered around the room. Our Thanksgiving gives rise to a prayer for you. By God's mercy, may you continue to flourish for uncounted years ahead. When Father Martin invited me to be part of this anniversary series, with the sole stipulation that I offer something for my particular interest and expertise, I determined that I would speak about liturgical praying. Praying liturgically has engaged me from my childhood and adolescence in Chicago, long before I had any words to name my interest.

[02:15]

I consider myself blessed to have had the opportunity as a Benedictine to study and to teach for many years in an area for which I have always felt a deep passion. I was an academic for probably 30 years, and I have been a prioress of my community for less than two. But I find myself in these circumstances reflecting on old questions in new ways. So my topic, a voice for the praying church. To spark your thinking about the kind of praying Benedictines do, Let me begin with stories. Three brief anecdotes and then a fourth to invite us to think about praying as very ordinary but also mysterious human activity.

[03:18]

The first story is recorded among the sayings of the Desert Fathers. So locate yourself in 4th century, the Egyptian desert. where a brother said to Abba Anthony, pray for me. The old man said to him, I will not have mercy on you, nor will God have any, if you yourself do not make an effort and if you do not pray to God. The contemporary American writer Annie Dillard recounts my second story in her most recent book, For the Time Being. Locate yourself in the 18th century in the company of Eastern European Hasidic Jews. Imagine, if you will, the mystery and magic of a world experienced at all times as diffused by the divine, the world of the stained glass and paintings of Marc Chagall.

[04:28]

As the story goes, a Hasid was traveling to a nearby town to spend the Day of Atonement with the Baal Shem Tov in the prayer house. Nightfall caught him in an open field and forced him, to his distress, to pray alone. After the holiday, the Baal Shem Tov received him with particular happiness and cordiality. Your prayer, he said, lifted up all the prayers which were lying stored in that field. The third story brings us to our own times. Mother Irene Dabolis, a Filipino-born Superior General of the Tutsing Missionary Benedictines, upon returning recently from a trip to visit her sisters in India, remarks that the Indian people have come to have deep respect for the Christian communities among them for their works of charity.

[05:35]

But they do not think of Christians, even Benedictine missionaries, as particularly gifted in prayer. To learn to pray, even Indian Christians are often turned to Buddhist and Hindu teachers. The fourth and final anecdote, also from the Hasidic tradition, reports the wonder that God prays. Rabbi Nachman of Bratislava said that God studies Torah three hours a day. The Talmud also notes that God prays and puts on phylacteries. What does God pray? May it be my will that my mercy overcome my anger. I savor these stories about praying because I've been thinking for a long time about prayer, trying to learn what it is and how to do it.

[06:45]

I first met Benedictines at prayer in my undergraduate college days, 1953 through 1957. only a short time after the Mount Savior community was established. I'm older than they are. I remember clearly what attracted me to the Benedictine way of life lived by the women who were my college teachers. Over the course of my four years, we students could not help but overhear them chanting the divine office in the choir, although at that time we never joined them. From a distance, though, it became evident to me that they knew something about praying and that I could learn from them. Forty years plus later, I am still learning. But I am now better able to understand what we Benedictines are up to and why, and also why what we do is a gift to church and society. Some of the questions and some of the answers were revealed in those stories.

[07:52]

Praying is an ordinary human activity, not something for specialists. So we learned from St. Anthony in the desert, unless you pray, God will not have mercy on you. Prayer rises from the whole of creation. So the stranded rabbi left alone in the field. We humans need to look for teachers of prayer. So, Father Irene Gabolis reporting on the search of Indian Christians. And God too has learned to pray wisely by spending time with the scriptures. My presentation is going to explore this in five points. I just alert you to that so that you can kind of count and keep tabs.

[08:56]

I'm a pretty good clock watcher, and I've spent years in a classroom with young people that start packing their books and squirming if you don't quit. So I'll also get that signal. And if one of the brothers rings the bell, I'll catch that too. My first point, why do Benedictines pray? I think Benedictines pray because we're human creatures and prayer rises from all creation. And I'd like to start by looking at our situation of being human in the cosmos. We're going to look at the big picture. In your imagination, pull out the many photos you've seen of our small blue planet Earth orbiting within the galaxy. Then locate that galaxy in your imagination in the expanding universe.

[10:02]

If you've read Brian Swim, Thomas Berry on the universe story, pulse of consciousness, their presentation of the big picture. Retrieve any awareness you have of the universe that astronomers and mathematicians try to conceptualize for us in a variety of models. Disney World, to the contrary, is decidedly not a small world after all. When we put ourselves in the big picture, We know that during our relatively brief lifetimes, each of us is on a great ride within the expanding universe. But we also know, from watching our family and our neighbors close up, that our ride in the cosmos will be a tragic one. We will flourish and then die quickly in the cosmic scheme of things.

[11:06]

Annie Dillard offered me a turn of phrase that helps me to locate us are humankind within the big picture. Dillard writes from the viewpoint of a modern Christian seeker living in a scientific age. She says, trafficking directly with the divine, as the manna-eating wilderness generation did, and as Jesus did, confers no immunity to death or hazard. You can live as a particle crashing about and colliding in a welter of materials with God, or you can live as a particle crashing about and colliding in a welter of materials without God, but you cannot live outside the welter of colliding materials. We know of what Dillard speaks. malaria, AIDS, shrapnel or bullet, car crash, explosion, flood, fire, earthquake, clogged artery, cancer.

[12:15]

It is hard to keep things in perspective, to keep looking at the cosmic picture of fatal collisions for a whole range of reasons. Ernest Becker argued probably 30 years ago now, in the denial of death, that were we humans fully attentive to the conditions of our existence, we would lose all capacity to function. We would be unable to get on with life. What we identify as psychological health, said Becker, requires that we develop strong egos, that we become individual selves with life projects making us worthy of being remembered by others. To children, we say, what do you want to do when you grow up? To adults who've been working for years, we say again, what will you do when you retire? But other thinkers, Dillard among them, defy the common sense limits, insisting that we pay attention to our human condition for the sake of our true self-knowledge.

[13:28]

Long before the modern scientific era, the psalmist wrote, and Dillard quotes, no matter how great, no one sees the truth. We die like beasts. No matter how wealthy, no matter how many tell you, my, how well you have done, the rich all join the dead, never to see light again. Life projects carry us only so far in coming to terms with our place in the divine plan in the universe. Philosophers in every era try to assess our identity as humans. The contemporary French philosopher Julia Kristeva summarized our paradoxical human condition in the epigram, I am mortal and I am speaking. I am material and I am spirit, self-aware. Another philosopher explains how each of us is a microcosm of the universe, and each woman and man and child, there is found everything that can be found in the entire cosmos.

[14:48]

That is, and each of us is found both spirit and matter. Our distinction We are that part of the universe of matter come to consciousness and responsibility. And having come to consciousness, we humans are able to wonder at a world not of our own making that we take in through our senses. And inevitably we discover, much as we resist the discovery, that we are limited and we have to die. These are the realities that evoke from us the response we call prayer. We wonder and are grateful for the gift we are and the gifts that have been given to us. But we are dissatisfied, restless, wanting more, without knowing clearly what it is we want. Put positively, as the German theologian Karl Loner did, we are impelled toward self-transcendence without knowing what will satisfy.

[15:53]

He coined the wonderful phrase, beloved of beginning theology students, talking about this capacity for self-transcendence. He talks about the wither of our transcendence. Who knows where or what it is, but we want more. We resist the prospect that the I that I am will perish and will be returned to earth, will vanish and be seen no more. Faced with death, we want to live. So it is good news that the story of Jesus, the story of the death of one known as a good man, invites us to believe and to hope. so much for the big picture. My second point is about Jesus as a revelation about prayer and about its outcomes.

[16:58]

As I just noted, modern scientists have recently gotten interested in telling the story of spirit in the universe, the story of the dynamism of a continually unfolding universe that started from nothing. Pre-scientific creation myths among all the world's peoples gave local accounts of how things came to be. And each generation taught the next how to respond to the mystery of existence as they understood it. Notre Dame philosopher John Donne once proposed that all cultures are organized to respond to that disconcerting truth, humans die. As Donne put it in The City of the Gods, one of his early works, each culture proposes an answer to the perennial human question, If I must someday die, what can I do to satisfy my desire to live?

[18:08]

Enter the story of Christ and the church. One of my younger sisters in community, reading theology this year, recently observed to me on the basis of her course on Christology and the cosmos, God is not the problem. How do we fit Christ in? We believe the story of incarnation as the story of the breaking forth of divine spirit into human history in the person of Jesus of Nazareth and the further outpouring of his Holy Spirit on those who would become the church. We have come to believe that if we keep our eyes on Jesus and open ourselves to the Holy Spirit of the risen Christ, it will be shown to us how to live well toward death in any and all times, places, and cultures.

[19:13]

To keep our eyes on Jesus, to open ourselves to the Holy Spirit so that we may live and die well, is the vocation of the Christian contemplative. It is, in fact, the vocation of all who have been baptized in Christ to keep our eyes on Jesus and open ourselves to the Holy Spirit of the risen Christ so that we may live and die well. As Abba Anthony warned that suppliant brother who had asked Anthony to pray for him, I will not have mercy upon you, noble God, if you yourself do not make an effort if you are not willing to stand before the mystery. Each Christian is called to develop a prayerful and contemplative spirit. And at this point, the question of teachers of prayer is raised. How can I pray unless someone shows me? Did Anthony teach that desert brother how to pray?

[20:19]

And if Anthony didn't, what was his path to the prayer of contemplation? And who has been teaching Christians in every successive generation how to pray? Why are those seekers in India looking for teachers every place but among Christians? The Hasidic rabbi noted that the source for God's prayer is scripture, Torah. Why should we not accept the wisdom of that story and begin there? What did God learn to pray for through the faithful study of Torah? If the story is true and there's no reason to believe that it isn't true, The God of Israel, who is the God of all nations, learned to pray thus, may it be my will that my mercy overcome my anger.

[21:20]

I love that line. It's a wonderful summary of the whole of the two Testaments, how God's mercy overcame God's justifiable impulse to anger. Quick summary, may it be my will that my mercy overcome my anger. Perhaps we too might pray for an abatement of anger in favor of loving kindness in all our dealings with our own humankind. In summary to this point then, there are two things we can know. First, the scriptures are a reliable teacher of prayer, and second, We pray in order to be reshaped so as to share in the mind and heart of God. The story of monasticism from Anthony onward is a story about seekers who gather around mentors who want to make the effort to pray to know the heart of God.

[22:27]

In Benedict's School of the Lord's Service, a couple of hundred years after the time of Anthony, serious seekers would come again wanting to know how to pray. Monastic seekers have taken the biblical songs and stories to heart, committed them to heart, memorized them in order to let the stories work within them, to let the songs work within them, so as to be transformed by the Spirit of Jesus. The Holy Spirit breathed in them through those stories and songs lodged in their hearts. By Benedict's time, formal traditions of monastic prayer had taken shape. And it is the formal monastic prayer tradition we call the Divine Office or Liturgy of the Hours that I want to speak about now.

[23:30]

My third point then is about official claims concerning the monastic liturgy of the hours. Church documents of the last two centuries have repeated the claim more than once and in a variety of contexts. The sole necessary work of monastic communities is prayer. The Dominican General Timothy Radcliffe recently offered to the Congress of Abbots his observation that Benedictines as an order in the Church have nothing in particular to do except pray. Unfortunately, civil authorities in modern European countries were not fully comfortable with that assertion in the 18th and 19th century. And in many different circumstances and political contexts, they mandated that monastic communities needed to justify their existence by doing something useful.

[24:46]

The utility of prayer in and with Christ not being immediately evident to moderns. The women in the Bavarian community, from which my community at Mount St. Scholastica derived, made themselves useful in 19th century Bavaria by becoming schoolteacher monastics. The lack of clarity about monastic identity and purpose, that resulted from the pressure to be useful according to predetermined cultural criteria, had a cumulative negative effect on monastic communities in the West in the 19th and 20th centuries. There have been many hyphenated Benedictine communities, schoolteacher monastics, all other kinds of working monastics. Because of the confusion, it seems to me as I listen to my fellow Benedictines that there has also been a decline in the courage of what I would call hyphenated Benedictine monastics to believe that the contemplative vocation can stand on its own as a contribution to either church or society.

[26:15]

What does your monastery do? we often ask one another. Jellies, candies, bread, cheese, caskets, schools, parish work. For the most part, Western Benedictines have all but succumbed to the value judgments of modern culture about being useful. Mount Savior's foundation story protected it somewhat from that history. Fortunately, the call to Benedictines to do nothing in particular but to pursue a public vocation to contemplative prayer continues to sound and is becoming louder. Yet the call carries with it correlative confusion at this time about the nature of contemplative prayer. Benedict's rule provides that monastics say the prayer of the hours. But in our day, many aspiring young contemplatives, some of them in Benedictine monasteries, wonder.

[27:24]

And here I'm quoting. a group of German Benedictines reflecting on their situation. Some think that choral prayer, they're talking about some of their own monks, some think that choral prayer, with its numerous words and images, far from leading to silence and contemplation, is a source of agitation and confusion. And those who think this way wonder with that requirement for hours of choral public praying, for manual labor, reading, community living, how can there be time for doing real contemplative work, sitting, centering, breathing, walking meditation as paths to contemplative prayer? Twenty-five years ago, the Congress of Benedictine Abbots published an authoritative, for us, directory for the celebration of the work of God.

[28:34]

The Abbots expressed no self-doubt, if they had any, about the Liturgy of the Hours as the work of God, the way into the heart of God. Using the theological vocabulary of the Second Vatican Council, the Abbots Directory called the praying of the Liturgy of the Hours the proper ministry of a monastic community. And with perhaps a nod to the die-hard utilitarians of the 19th and early 20th centuries, they identified the Prayer of the Hours as a ministry useful for the building up of the body of Christ. But I think we still need to understand just what is being said about prayer as the proper ministry of Benedictines useful for the Church. How is our choral praying of Liturgy of the Hours, the choral praying of Liturgy of the Hours that takes place in this space, a proper ministry for the body of Christ and the world?

[29:46]

How is it even valuable to the monks themselves? We have to rule out the easy answer. It was one that was found in the commentaries in my own monastic formation. Whatever Benedictines are doing when we are engaged in the work of God, in the liturgy of the hours, in the office, we are not spiritual mercenaries for busy people. Abba Anthony had already warned 1,600 years ago that you couldn't do somebody else's praying for them. God will not have mercy on you if you yourself do not try. Unfortunately, the sense of being spiritual mercenaries has surfaced more than once in monastic history. We can think of a long medieval period when monastic foundations were paid princely sums to pray for the salvation of their benefactors when the benefactors themselves were commonly engaged in counter-salvific activities.

[31:03]

As I've been thinking again then about why we as 21st century Benedictines still commit ourselves to praying in choir as a community and calling this choral prayer our proper ministry, I was heartened to read from those same German Benedictines that they had decided to face the question as a matter for both communal and public reflection. They'd been talking about it among themselves. They'd been talking about it with friends of the community for several years. And in a recent issue of a Cistercian publication called Liturgy, they had published a short statement of some of the insights that they had come to. The monks' reflections confirmed many convictions of my own that I had not yet in any way made any effort to put into some clear order. But encouraged by them, I would like to say something further about, I think, what is the particular role of Benedictines, and hence my title, A Voice for the Praying Church.

[32:16]

This last observation is my own and it is subject to your response and validation or refusal to validate since my claim is also that the whole church is praying. But I'd like you to think about Benedictines and other communities, as with our contemplative Dominican sisters here, communities who commit themselves to public contemplative praying, or commit themselves publicly to contemplative praying, as a voice for the praying church. My first presumption in this is that everybody is praying. Because the one we seek in our desire to live is always already stirring within us.

[33:21]

During our daily crashing and colliding with the materials of the universe, Divine Spirit is stirring in the whole creation. In the ongoing melee on this planet that is our home, everybody is praying. Even when the words spoken sometimes sound to our human ears like nothing more than cursing, the Psalms have succeeded in showing us that even those cries of bitterness and anguish can be the beginning of prayer. St. Paul goes further, assuring us that the Holy Spirit is praying at all times with sighs too deep for words, helping us in our weakness, interceding for us when we do not know how to pray. I'd like to talk about the monastic choir, but first I'd like to reflect on the larger human context in which this rural choir ministers to the whole church.

[34:39]

I lived in Washington, D.C. for probably a total of almost 25 years. back and forth with my community. I wasn't gone for 25 years. And it occurred to me there that as I rode a public bus or a subway during the morning rush hour, you would see some commuters with Bibles open in their laps, reading scripture. Many others would sit in self-contained silence, faces masked, But if you spent time attempting to get a sense of what was going on, you began to recognize that those masked faces were the faces of people full of interior longing or despair or delight or gratitude or perhaps seething with anger at betrayal.

[35:48]

Human aspiration and passion, despair and happiness pervade the morning air in the rush hour. Every person that we observe, every person that we can imagine moving back and forth from home to work, work to home, is linked in their interior longing, interior despair, to unseen others in hospitals, in jails, in the homes, in the offices, in factories or fields or schools. But let's not limit ourselves as we think about this context of the Benedictine monastic choir. Paul and the psalmist and the Hasidic rabbis tell us that the striving of spirit in the world is not limited to our self-conscious humankind.

[36:55]

The very fields around us are full of prayer. Wildflowers and grasses reflect back the glory of the Creator. Fields with stagnant ponds and trash wait with eager longing to be set free from the bondage to decay. Wait for the redemption of our humankind, says Paul, so that they may obtain the freedom of glory. Because our humankind does not know how to pray as we ought, says Paul, the Holy Spirit helps us in our weakness. And it's in this juncture of unknowing that the Church enters in and the Church is the context for the monastic choir. It is true that Spirit is active everywhere in the universe, Divine Spirit. Yet the Holy Spirit of Jesus of Nazareth, the risen Christ, is being continually poured out in a special way on the Church.

[38:04]

It is this Holy Spirit of Jesus that shapes the community of the baptized, the body of Christ on earth. The church is an odd community. We can all offer our explanation of its oddness, but the only point I want to make is that it is a community resident in virtually all living cultures, and it is a community that transcends every culture that it is in. The theologians a half century ago called this odd global community the mystical body of Christ. Now, just as the Church has been expanding globally and now is found visibly across all lands, continents, islands, and so on, in a parallel expression, we know that monastic choirs are everywhere forming for the Prayer of the Hours in the Southern Hemisphere in Asia.

[39:13]

There's an explosion of young monasteries in all of the developing countries. We might wonder why this rapid expansion of monastic choirs. I don't know, but I've thought about it. And it seems to me that if we think about this from a doctrinal perspective, the church calls itself a priestly people among all the peoples of the earth. But what is the priestly identity of the baptized? For many generations, Catholics have equated priestly identity with ordination to church office. Yet in an earlier era, peoples and cultures have understood the role of priest more basically as the role of intermediary.

[40:14]

In the words of the scripture, the priest is designated to go between the porch and the altar, the porch being the place where those who were not initiated into the faith community stood, and the priest, well, the porch of the unbelievers, but also the porch of the ordinary folk, and then the priest went back and forth between the porch and the altar. It was understood that the priests could negotiate this connection because it had been revealed to the priests who God was and how to approach God, voicing on behalf of others what needed to be voiced. It's within this frame of mediation that the whole church has its priestly identity. For it is to the whole Church that the mystery of Christ has been disclosed for the sake of the rest of the world." In biblical language, Christians are ambassadors sent to deliver good news to the whole world, but also Christians are priestly advocates by Christ's Holy Spirit for the well-being of the world.

[41:35]

So it is not surprising that monastic choirs arise wherever the church is present, arise to embody the voice and the prayer of the church. To underscore my point, let me ask you to return to those people praying on the subway and in buses, in their cars and in their trucks. However much they are filled with pain and longing, gratitude and delight, Many, if not most, are short on language adequate to speak about their deepest desires and regrets. In them, and in people like them all over the world, the Holy Spirit is undoubtedly praying, even as they themselves doubt whether they even know how to pray. Others among the commuters commuters, baptized into the body of Christ and shaped by the faith of the Church, have learned how to draw the world's inarticulate longing and their own longing into focus, identifying every human experience with the life, suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

[42:58]

But the morning prayer of commuters like the morning prayer of much of the world, remains inaudible and invisible. But if prayer is to follow the law of incarnation, Both the inarticulate prayer of the human heart and the interior prayer of the body of Christ stands in need of release into the world of conscious matter. The prayer of Christ needs voice and body, the body and voice of the Church in human history. Embodied prayer has a living history. Just recently, we've seen news reports of millions of Muslims embodying their desire for connection with God in their hajj to the Arabian desert. We've heard reports of countless Hindus bathing naked at the confluence of sacred waters at an auspicious time in the festival season in order to make connection with the divine.

[44:13]

Jewish men wrapped in prayer shawls sway and chant daily at the Western Wall. Buddhists sit. Embodied Christian prayer, too, has a living history. But Catholics and Christians generally have lost confidence in our most ancient traditions of embodied prayer. Christians in modern Western cultures, including Catholic Christians, even including some monastics, are allowing themselves to be persuaded that embodied communal prayer is antithetical to true contemplative spirituality. True spirituality in our culture is being redefined primarily as a matter of personal interiority, personal growth. Time spent praying communally in and with Christ for the whole of creation does not have much attraction.

[45:17]

After all, ours is a world where successful people are those who are able to make it on their own. In this context, it's worthwhile to look again at the tradition of embodied prayer that Benedict offered his monastics. Monastics assemble with regularity several times daily. In assembly, they make visible, locally, the mystery of Christian identity as a priestly people. In the monastic community, In mine, of course, we are all baptized laity. In this community, a few are ordained, but the shared priesthood they exercise is this audible song of praise, lamentation, and pleading arising from their common baptism in the Spirit of Jesus. The morning and evening offerings they raise to God are sacrifices of praise, songs of lament, songs of trust, confidence, and petition.

[46:27]

In solidarity with the whole of creation, the whole human community, and the whole church distracted and occupied by many other responsibilities. Monastic communities are free to assemble regularly because, except for this embodied praying, monastic communities have nothing in particular to do. Like God, if Rabbi Nachman of Wroclaw had it right, Benedictine monastic communities at prayer stay close to the sacred text so that they come to understand more and more clearly for themselves what it is that God wants and how they should be approaching God on behalf of the world. By staying close to the biblical word of God, the shared heart of the monastic community is worked over daily by the Holy Spirit. And each individual monastic is also invited to put on the mind of Christ, not without difficulty.

[47:33]

It takes a lifetime. But as Saint Augustine knew, our praying the Psalms does not have as its purpose the edification of God, but rather the purpose of directing our human desire toward what God desires. Augustine and many other early monastic teachers of prayer, including Benedict, were confident that praying the office daily and living from the biblical words, being voiced, being heard, and shaping one's heart was a sure path to the formation of the contemplative Christian. We come then to my last point, that the about the usefulness of this prayer for the church and society. I think the claim that this is a useful ministry for the whole church has some implications.

[48:42]

The first of them relates to the matter of monastic hospitality. The second has to do with monastic identity and presence. People everywhere in our time are seeking spiritual formation and spiritual direction. Researchers and general cultural observers agree that our nation is currently caught up in a quest for spirituality and also a hunger for things traditional. But we can get pretty eclectic about how we approach what we are looking for. This is specifically the case for young people and young adults who experience themselves as ungrounded in this cosmic colliding that is human existence. So they're searching everywhere for roots, for meaning, for traditions. They often search alone. They feel that the parish church and local congregations fail to touch them because, except for sacramental liturgies and occasional devotions, not much praying happens in parish churches.

[49:46]

Young people suspect that there is something more, and they're on the lookout for guides, for mentors, for gurus, people who seem to know. Books, tapes, short workshops available on the open market promise them sure and relatively painless ways to spiritual enlightenment. In their search for spiritual enlightenment, they are vulnerable to charlatans and self-promoters, to spiritual fads, and to religious romanticism, as I think most of us were at some time in our youth. The Benedictine community at daily prayer, gathered several times daily, voices the ancient and living prayer of the Church, the prayer of the body of Christ. There's nothing faddish about it. It is a living tradition that reaches back into the earliest period of the Church. In our public praying, monastics invite seekers to consider genuine alternatives to understanding the nature of spiritual discipline and the prayer of Christ, understandings that are perhaps more profound than some of the others that are available to them elsewhere.

[51:03]

So if the 21st century benediction community gathered for the prayer of the hours is to be a community ministering, especially while it is praying, such a community will exercise generous welcome and attentive hospitality to those who wish to join them to themselves give voice to the prayer of the church, if even only for a short time. To welcome others in, to welcome them into prayer and to invite them, is to invite them into the heart of God and the mystery of the divine plan. If something is useful, it must have advantages and benefits. Let me suggest a couple. Monastic communities of prayer have the freedom to be visibly ecumenical. As the prayer of the hours, there is no need to warn Christians of other communions of our separation.

[52:05]

nor of formal boundaries we must honor, as is the case with our current Catholic Eucharistic discipline. The hours are voiced not only for but with whatever part of the disunited and divided praying church wishes to join. This is a prayer which overcomes and transcends the boundaries and barriers which separate Christians. Monastic communities of prayer also affirm the identity of all the baptized as one priestly people in an era when ecclesiastical rank is known to rankle. and tensions grow up between the ordained and the merely baptized. The prayer of the hours shows the church to itself as a priestly people joined to the prayer of Christ. All together sound the lament of our humankind. All together sing praise. All together give thanks. All together ask for deliverance, forgiveness, and divine mercy. Hospitality extended to the whole Church at the Prayer of the Hours can be both evangelical and healing for Christians struggling with their Catholic identity.

[53:15]

The Prayer of the Hours is also beneficial for monastics. We don't just do this for everybody else. The Liturgy of the Hours affirms and deepens the monastic identity of those who have publicly promised Benedictine monastic conversatio. Let me make two observations on this point. First, the hours are terminal, and the gathering for the community hour by hour, day by day, year in and year out, is itself a community-forming practice. Community forming practices in a Benedictine monastery are ascetic disciplines, opportunities for mutual forbearance, for welcoming the mysterious other in my brother or sister, asking me to give up my convenience for the sake of entering with others into the paschal mystery where new life opens up through our dying to ourselves.

[54:22]

Secondly, the monks' chanting of the biblical word is an induction into the heart of God, where mercy and compassion do prevail over anger. Chanting the biblical words faithfully, Benedictines, privileged to voice the prayer of the whole Church, are invited to understand that the Creator of the universe knows and accepts our humankind better than we know and accept ourselves and one another. To come to know this mystery that God's mercy prevails and to believe in it is to be a contemplative Christian, a mystic. Gregory the Great tells us that Benedict at the end of his life saw the whole world suffused in light. Gregory tells us that Scholastica knew that the heart of God was loving kindness and that even the storm and rain clouds conspired with her to let love prevail.

[55:25]

Thomas Merton reports that for a moment he saw the people of Louisville bathed in radiance. Benedictine communities within which the mystery of God is heartfelt because it is heard and received will be places that attract others. Such communities are attractive because they know something. However inarticulate monastics are, and I'm probably one of those who is uncommon for being very articulate, However inarticulate monastics are, people seeking spirituality find monastic communities. In the past, visitors were often satisfied simply to have been in the monastic presence. We went over to the monastery the other day and we looked around. At present in our new cultural circumstances, I doubt that that's any longer enough.

[56:29]

Seekers want and need more from monastic communities. The Catholic people's identity, and here I mean the Catholic people ordained in lay, need to be suffused with the message of divine compassion and loving kindness. The ministry of prayer already affirmed the notion that we give voice to the praying church I think is evolving, not necessarily by our design, but in response to the Church's great need in our time. What would it mean for Benedictine monasteries, now located on every continent in the globe, intentionally to commit ourselves to become, in whatever formal or informal ways are appropriate, to become local schools for prayer? Our world needs places where mercy and compassion and loving kindness for the world's suffering are able to be linked directly to the prayer of Christ and the mystery of the divine design.

[57:31]

The people of this part of New York are already blessed that Mount Savior Monastery ventured onto this path 50 years ago. Thank you. Well, really, if anybody has any questions or comments, or... I'm so scared. This is just a comment. Why would you pay an officer to pass it? Sir, I mean, here's my witness. I mean, the witness that I asked him, he said, in the last six or four or three hours, I was doing a lot of work, still a lot of work, still a lot of work, and then I almost threw up. Right? It's real true. It's really true. It's the heart of being on fire. It's the way that you change. And sometimes they never say it like that. It will be different. Most of the half-breds that I've seen, I think, have been trying to speak up, but I don't know where they were when I met them.

[58:37]

I think they've got to speak so that you know where they are. So you were worked on in other ways at that point. I think that it is very clear, though, that this is a great privilege that we have, that we have the opportunity to let the biblical word and the scriptural word work on us. But it strikes me also, then, that if that is the case, that hospitality to others and a capacity to guide others and show them the way is a responsibility that is becoming clearer and clearer. And as I said, I think that our monastic communities have a responsibility to pursue that in whatever formal or informal ways are appropriate to their circumstances.

[59:42]

But it is clear, and the numbers who come here indicate that from time to time at least, people want to give voice to their prayer. They want to join those who are doing it. but they also want to be worked over by the Holy Spirit. They want to have their lives opened up, cracked open, and to be able to go out with confidence and to minister to the suffering and the anguish which is in the world. Yes? I don't know if you can hear me. I don't know because that's no help, but I was going to say I have worked with young people for some 20, 25 years, and I think that it's extremely difficult, but I think that one of the things that

[60:49]

they need, and one of the things that they are very often looking for, is someone who makes sense to them, somebody who is credible to them, and very often it isn't their parents. And through no fault of your own, through something of the human development process. And I think that, as I said, with regards to the many monastics in the Western Church, that emphasis on being useful led many of them to lose confidence in the fact that the prayer that they had to offer and the prayer that they themselves were learning was something to be shared. So I think that we find the phenomenon that many places where there were Benedictine schools for generations, they very seldom really touch the heart of young people because we were busy doing one thing and not really talking about these other dimensions of our lives.

[61:54]

So I think that in some ways the church is at fault because we have not been teaching prayer. And so it's not surprising that they go looking everywhere else. Those of you who have the time, you may want to look at the section on prayer in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. It's the fourth part of the book, and many, many commentators say it is the best part of the Catechism in terms of its teaching on prayer, but of course you can't give that to a young person. You've really got to have them find a mentor who is somehow going to teach them to pray. And so one of the things that we are doing in my community right now, just out of this kind of awareness that young people don't have contact with praying communities because of the circumstances of the church and public life. We've begun intentionally beginning a youth ministry at the monastery and simply inviting them in and while they're there having them pray with us once or twice, just letting them discover there's a whole part of the world that they don't know about and that they're welcome and trying to encourage return visits and so on.

[63:15]

I don't know whether it's going to make any difference in the long run, but we figure it can't hurt. And we'd like at least to let them see and to hear and be a part of something and be touched by it so that their curiosity is aroused. Yes. I'm somehow new in some way. Maybe that also speaks to the young. I don't see that. It's hard for them to understand the language of the tool, whatever, so it may be a strange approach. I think that when I'm talking about romantic spirituality is an attempt to put on a persona without having done the hard work of getting at the reality, but I think that the whole question of

[64:35]

I lost part of your question there. But that's all I meant by romantic spirituality. But I think with the younger generation, there is this tension right now, which it also can be somewhat romantic, of young people feeling that There is a church they never knew and that they've somehow been deprived of that church and there's a certain kind of retrieval and a certain kind of archaism and in a selective reconstructing of 1950s Catholicism, you know, they pick pieces of it and then turn it into this is the way the church really should be. And I think that that search for knowing the past and knowing the tradition and not feeling that they are deprived of their Catholic identity and the richness of Catholic life and Catholic culture is very often explored by them, young people, in fairly superficial ways right now. And so one of the things that we've been doing, and just beginning, just beginning, but we have a young sister in our community who has worked as a youth minister before she came to community.

[65:49]

And so she's begun to try to transform. transfer what she learned in working in parishes into youth ministry at the monastery. But one of the things that we are risking doing is really welcoming them into, rather than modifying for them, letting them join us. Now, we don't think that's because this is going to be something that's going to hold with them forever, but her work is to help them reflect on those experiences and try to figure out how they connect with their own experiences and so on. But I think that it's, the work is the constant connecting, constant connecting. And it has to be done by those who are able to reach out and minister to one another in loving ways. But I think that absent that kind of genuine teachers who work with them and are concerned about them, they are going to reconstruct in any way they want.

[66:53]

And young people, because of the media that they have contact with, live in virtual worlds where they can mix and match and change things through, you know, films and video and editing and so on. And they tend to do that with traditions, to pick out the pieces that they want, but to put together some kind of an assemblage of things that may or may not really have any hard, deep spiritual struggle or integrity behind it. And then of course because it doesn't satisfy they keep the work of reinventing. So hurry, and if you never do go to church, for those who have left it, or those who have come in again, then there are certainly thoughts, prayers, and others, but the crowd in choir are going to be seeing better than that.

[68:04]

As I mentioned with the prophetic observable, this market sits on a lot of ground, and it seems to be making landings from the priesthood. are automatically corrosive. And it's worse. If you were a guy who just wore a handkerchief, let it be out for a while. So I think that's maybe part of it that got me mixed with some of the people I keep searching for research about ill or religious or spirituality. And that incident left the whole question of the nature of ill presented with this bond of that corrosive. I think what the researchers of young people at the present time are telling us though is that those of us who are in the generation that you're describing have to be very, very careful that we don't presume that this is the younger people's experience.

[69:10]

And in some ways, we have been told in religious communities, for example, that we are always in danger of putting our agendas on young people coming to us who don't have those same agendas. So the young people that are coming to religious life now may have all kinds of anger and pain and trouble and so on. Very few of them are coming feeling terribly guilty. that they've lived in a culture which is a kind of a guilt-free culture. And so they have a different starting point, but I think the starting point of identity and meaning in their lives is a much stronger starting point for them. And if we are caught up in the guilt and repudiating the church which we experienced as having damaged us in some way, in a sense we may be those who are blocking their access to the tradition in its richness and because we have been so marked by some of the narrowness of the tradition.

[70:18]

Yes? One by one. The question was posed, how do I approach modern women who lament the restrictions placed on them by the church? My comment was partly off the cuff, but also the complexity of that is so real in terms of what different people's perceptions and agendas are that I generally try to find out, tell me what's going on. But I think fundamentally we have to acknowledge that there is a lot of inconsistency and a lot of really negative behavior toward women. I think that Those of us in women's communities are protected from it in some ways that make us both sources of encouragement but also maybe bad filters for what ordinary women's experience is.

[71:37]

Because we do have the luxury of working with our own prayer, planning our own prayer. In my community, for example, we simply follow a a practice that we've done for 25 years. We're not allowed to preach during the Eucharistic liturgy, but we have a Saturday night vigil for the Sunday, and during the great seasons of the year, Advent through Christmas, and then Lent through Easter, we take turns preaching on the Sunday gospel. So we, in fact, in communities, have the opportunities to do some kinds of things that I think women in the church find themselves, every time you find a place where you can do something, You know, somebody runs around and tries to close the door, unless you can keep figuring out how to outsmart the system. Because there is a very, very conscious and deliberate attempt right now to shut down avenues that seem to be opening up sometime earlier.

[72:39]

I think, again, something I can tell you, the Leadership Conference on Women and Religious had reached a point of frustration a number of years ago and just reflecting on this and began to start taking a completely different tack in terms of saying this is a battle that is not going to be won by aggression and pushing because Nobody's moving. And so the decision was made that we really needed to, and God help us, it sounds a little bit late to figure it out, but we really should be spending a lot more time praying for the church and praying. In my own community, we translated this into a program of befriending a bishop. We have about 65 sisters who each have chosen one of the bishops.

[73:41]

Some of them have taken bishops out of the country. I don't know who Cardinal Ratzinger got, but somebody decided to befriend him. But basically, what they're doing is praying intentionally daily. We pray in the Liturgy of the Hours for the bishops we've chosen to befriend, but really attempt to enter into what are their struggles? What is it that's blocking? the ability to deal more realistically with the church. We've invited and committed ourselves to writing letters to them occasionally, but not to give them our agendas, simply to write them letters of support and encouragement, and to really see that this is a situation which calls for prayer. I mean we're at a point where negotiation has not brought about too many changes and so fundamentally the spirit is the one who is going to bring about whatever changes are needed if we do our part. Yes, this probably should be the last question.

[74:44]

Well, today works kind of. The idea of a school for your reasons is still important. Someone asked the question of what do you do with the kids, et cetera, et cetera. I think there's always going to be tougher parts of a lot of the process, and it's all included, to pray. Because, I say to God, because we feel uncomfortable ourselves with our maybe inadequacy, to actually be able to pray. And what's interesting is that he made you run around and around and around and around and around and around and around and around and [...] I'm a facility-owned person who has not had many opportunities to actually pray in public.

[75:55]

And often what I have perhaps to offer there, I feel, I honestly feel, you know, somehow glad about it. And I think it's maybe soul prayer, you know, or I don't know, support of the good faith. Yeah, and yet, and yet my, And yeah, I was going to say, my guess is that even though you feel inadequate that you've been praying all your life interiorly and in the inarticulate way that you feel. But the question of a freedom to be more comfortable with that is something that I think that the whole church, we need to help one another. That's very true. Yes. These things, in my own time, is where I thought it's important. It's not there where it's important. I feel like that's where it's important. Then you have to be on the stage of kind of perfection in order to say the word. of the fact that we are, who are coming forward to us as we are, it's usually put in the middle of the house.

[77:07]

When the brothers get a telephone appointment, they run out of what to keep, and they run out of that. These are the things, like, that shouldn't go to here, possibly. believe in it, but we don't do it until we've got some words in it. And so I have to come out of our guilt sometimes, thinking that's the right words, and we have to be able to stay in the grace of God, so I think the rest of it works quite honestly. And that notion that we're not good enough to pray, I think is something that the Psalms help us to see very clearly, that the words of the Psalms show us human beings in all stages and sentiments and moods. There was a number of years ago, and actually the Roman liturgy did suppress a number of the Psalms which were perceived as being possibly too harsh for God to take, or maybe too harsh for us to take. But there is a sense in which I think it's important for us to pray even the harsh words of the Psalms, the words which are words of anger and rage and outrage and betrayal and so on, because somewhere

[78:23]

and maybe in my own heart, those feelings are there. I mean, these are human feelings. And even these can be offered to God. And that we don't have to be ashamed because out of that, this is the beginning of prayer. The beginning of prayer, just to know. I think that One of my favorite stories is, well, I'm not going to go into it. Let's just stay with the point that you're making that we sometimes sanitize prayer also. We try to say that only really good people can pray or that somehow or other only the prayer of good people would be heard or only good prayers can be received. Well, that you're talking about prayer being a relationship with no words at all makes me think of the story that I was going to tell, and I will tell it.

[79:26]

Some of you are probably familiar with it. The Nobel Prize winner, who had written extensively about the Holocaust, tells the story about how on the day that he was to say the prayer, a Kaddish praising God, on the occasion of the death of his father, he refused to pray the prayer because of the death that his father had died. And that each year on the anniversary of his father's death, he remembered and refused to pray. That's not nothing, because the refusal to pray was an acknowledgment of a relationship that if he had simply forgotten the whole thing, there would have been a real loss. But he himself tells how eventually, over the years, after years and years of refusal, one year, whatever healed in that relationship, he was able to say the prayer.

[80:26]

And I think that, again, we might look at that as a resistance to prayer, but the remembering and refusing is at least still connecting. Yes. Yes. Yes. And I'm sure the area has been touched in many ways just by the presence here of these two communities. Yes. And he said that the terrible of the woman who kept my vagina very persistent, and the dress was very silly and faded. The public heaven, if you advance it, you will understand it.

[81:42]

The Bible says that being able to speak to the Lord in any form, you will reign in the Holy Spirit, and the Holy Spirit is the one that gives you peace, love, friendship, and mysticism. We have a world of people that are informing their lives, And yet I think those conversations need to go on because you do have people who think they don't know how to pray. And that leaves people at a loss when, in fact, they may have gained and made great grounds in their life in authentic prayer. But the conversation that helps us to understand this has to take place. I said last, but I guess there's one more.

[82:43]

Yes, I recognize you now. Yes, I do. Yes. I think definitely it is, but I think that not every way of being is contemplative because I think that the way of being which is fully contemplative from a Christian understanding is a way of being which is connected with the heart of God through the heart of Christ and that to arrive at that way of being and to, as I said in my way of summary, to be at a point where one's compassion for the world evokes one's love and compassion for the world.

[84:02]

Seeing things as God sees them is one's normal stance, is really to have arrived at a contemplative way of being. And most of us struggle with that. We're pretty sure that God doesn't have it right, and that at least some of these people need to get shaped up. Whereas if God were shaping up everyone that needs to be shaped up, we'd all be in big trouble. So I think that probably is the last. Thank you very much for the conversation with you. I enjoyed it. Now, we can have vespers almost immediately. And then after vespers, we're invited to the refectory to have some wonderful refreshments.

[85:03]

I walked through there earlier. And then if you can stay, a compliment will be when we've eaten most of the food or people are about ready to go home.

[85:11]

@Transcribed_v004

@Text_v004

@Score_JI