You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Awakening to Divine Presence

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk emphasizes the dynamic concept of the Spirit in Christian theology, primarily through the letters of Paul, as a transformative power paired with Christ that contrasts with more aesthetic experiences of the holy. Exploring Old Testament visions, like Ezekiel's, reveals transcendent themes echoed in New Testament writings. The importance of the Spirit in prayer and the Christian journey is highlighted, alongside reflections on monastic life and the Beatitudes' paradoxical blessings.

Referenced Works and Teachings:

- Letters of Paul: Explored as texts where the Spirit is described as a transformative power.

- Galatians: Referenced for identifying the fruits of the Spirit.

- Isaiah 6: Noted for the vision of Yahweh and its influence on worship traditions.

- Ezekiel's Visions: Examined for their representation of transcendent divine encounters.

- Epic of Gilgamesh: Discussed for its narrative on human mortality and the search for immortality.

- The Beatitudes (Matthew 5): Analyzed for their paradoxical meaning and encouragement of spiritual virtues.

- Romans 8: Described as a chapter exploring the conflict between the spirit and the flesh.

- Rule of Benedict: Cited in the context of monastic guidance and limitations.

- Shema (Deuteronomy 6): Highlighted in relation to the commandment to love God wholly.

AI Suggested Title: Spirit's Transformative Journey

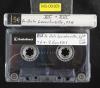

Side: VII

Speaker: Fr. Dale Launderville, OSB

Possible Title: Conf. 7

Additional text: 3:15 p.m.

Side: VIII

Speaker: Fr. Dale Launderville, OSB

Possible Title: Conf. 8

Additional text: 7 p.m.

Side: A

Possible Title: Conf. 7

Additional text: Retreat 2009 ... 6-9 June

Side: B

Possible Title: Conf. 8

Additional text: Retreat 2009 ... 6-9 June

@AI-Vision_v003

Two talks from this date

Our help is in the name of the Lord. Well, this one I entitled, Awareness of God, Receptivity and Focus. We've probably all had the experience of being in a building all by ourselves at night and perhaps feeling a little bit spooked by it. And it seems as if there's somebody else that's there. And if we were spooked, our perception of this other being, whether it was a ghost or a spirit, was that it was unknown and probably not very friendly. And we can go, psychologists can offer us all kinds of explanations for this, but when they finally get down to it, they never are really that satisfying. That there is something about our experience that tells us that there is a spirit world, And from the most ancient times, they've talked about having access to this dimension of the Spirit. And we know that the notion of the Spirit is really prominent in the letters of Paul.

[01:07]

When we examine all of the instances of the Spirit in those letters, it seems that what the Spirit is, is a power. And it does not really have the contours of a personality when you read through Paul's letters, except when it's paired up with Christ. And then the spirit takes on this sort of person, personhood or the person characters or personality of Christ, which is then communicated through the spirit. So, somehow that reality of spirit as being power, I found very helpful. There is an affective dimension to our experience of the Spirit. When we read through Galatians, it says that we are aware of the presence of the Spirit in terms of love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, humility, and self-control.

[02:08]

In later theological works, as you move through the tradition, the activity of the spirit and the believer will often be rendered in terms of sanctifying grace. that reality that brings us into the sphere of the Holy. But when you're dealing in biblical terms, sanctifying grace is usually not the term used. The term that's more dominant would be the activity of the Spirit that then gets translated into that. So the experience of the Holy in a dramatic way probably has a place in all of our lives, at least we would hope for it. And it may be the beauty of the sunset, or the wondrous presence that comes about from hearing choral music, very well done. I can recall at a funeral of one of our abbots about 14, 15 years ago, the monastic school did this version of the Ave Maria, which our abbey church was built for having like 150, 200 monks in full voice echoing off of the cement that it's constructed off of.

[03:20]

And it was really built for Gregorian chant in terms of the acoustics, so a lot of times we're very challenged in trying to make ourselves heard in the place. But for some reason, when the skola did this Ave Maria, it just echoed in such a, it was like you were transported into another sphere. The only other time that I had even half of an experience like that, there's a church outside of Jerusalem called Abu Ghosh. And there's a type of architecture in Jerusalem which is called Crusader churches. And those things, you can go in there and the acoustics are just ingenious, the way they put it together. But there was this, at Abu Ghosh, there was a small monastic group that was forming back in mid-80s. And they did their office in there. And for some reason, that it just, it almost transports you when you get, when you hear that. So, our experience, aesthetic experience, that can draw us into the sphere of the holy.

[04:25]

But much more powerful experiences of the holy that rise above the aesthetic would be something like, perhaps what we would say Moses at the burning bush, or when Jacob had the experience of the vision of the ladder. Those places, there was some sense in which they talked about there's an awesome presence here. There's something numinous that really draws us into another level of reality. And another place that it's very pronounced, which we, in the Eucharist, are holy, holy, holy, of course, comes from Isaiah chapter 6, in which Isaiah has this vision of Yahweh lifted up in the temple and the seraphim there are shouting this praise of holy, holy, holy back to him. And we know that at that point Isaiah was really overcome and he declared that he was a man of unclean lips. And then one of the seraphim takes a hot burning coal from the altar and purges his lips, and that somehow was a sign that he was empowered by God at that point, because when God says, who will I send, immediately Isaiah, after feeling overwhelmed by this experience, is ready to go forth.

[05:45]

And so, a very dramatic experience of the holy. The one that really tries to get our imaginations going, though, is Ezekiel's inaugural vision. And there, you almost end up saying, do I really know what I've seen after I've, you know, you hear it described. Apparently, one of our older monks, a generation or two ago, who used to teach Old Testament, he apparently had some way of acting this out. Because I mentioned this chapter to older conferers, And they say, oh yeah. And then they start going like this. They start acting. He was a very dramatic character, I guess. He used to act out all of these. But he gave them somehow a visual image of this. And I don't know how he did it. Because when you start thinking about what's described there, you've got a storm cloud coming in from the horizon. So it's like a... a really very active thunderhead that's coming in with lightning, flashing, etc.

[06:50]

And so he talks about the four corners of this as if they're the four corners of Yahweh's chariot. And on each of those characters that's a cherub that's at the each of the corners each of them also has four heads so you got four cherub four heads and so you're getting universal symbolism in this but you what's in it's very uh uh puzzling about this is that these four creatures all seem to be independent. You have four faces, which would seem like you'd have a lion wanting to go one way, an eagle wanting to go the other way, human this way, and I forget the last one, but it's the ox I think was the other one, goes the other way. But the text says that the spirit, which you'd think of was that the power of the thunderstorm, the wind that was in the cloud, was in each of them. And so it directed them to go in the way that they're to go.

[07:54]

Now, so at that point it all seems coherent. You've got four faces, but they're guided by the spirit. But then he gets into the middle of this and he starts talking about, but the appearance of it was like darts in a very intense kind of campfire or something, a fire that was on the, and they keep darting here and there. And the cherub were the ones that were going back and forth. And so you wonder, you're left not really clear what's going on in this. You get a clear, what is powerful in it is you get a sense of transcendence. And so they were taking traditional images of God coming in the form of a thunderstorm, but yet he was putting this together with these humanoid characters called cherub that somehow were were infused with the Spirit and therefore could move this chariot forward.

[08:57]

And all of that is by way of saying that this Yahweh who's enthroned above that is above, if we can't comprehend very well what the throne bearers are like, then the one who's above it would also be much more transcendent. But Ezekiel does this because he starts talking about Yahweh as fire to the waist up, and then Electrum the rest of the way, I think, or vice versa, but he almost talks about God in humanoid form, which everyone else stops at the feet. They'll talk about God as having his feet on the pavement, but they won't go so far as to talk about who he is. So, a very complex kind of vision of the holy. And so, by way of thinking in New Testament terms when we start thinking about Paul's experience of the Spirit. The experience of the Spirit within these Old Testament texts is that it's a reality that's much more overwhelming, much more powerful, because when Ezekiel sees this vision, he's down on his feet.

[10:09]

But then it does talk about the spirit that Ruach goes into him and lifts him up and puts him back on his feet. So we're starting to take a step towards some kind of indwelling of the spirit. There was a colloquium at our place, our ecumenical center about 10 years ago, Jewish-Christian dialogue. And they wanted to talk, what's the difference between Jewish and Christian prayer? And one of the key things is in Jewish prayer, they don't talk about the indwelling of God in the person while they're praying. They will talk about the Torah and being fed and energized and etc., but their conclusion in that dialogue was, is that this kind of imminent sense of God being in a someone is really an innovation, a new thing that comes along within the Christian times. So, this experience of the holy then, which lifted Ezekiel to his feet, it's the same wind or spirit that was in the storm cloud, and this accompanies him then throughout his ministry.

[11:27]

In fact, Ezekiel was somebody that, he was muted, And you wonder, well then how do you talk? And apparently it was when the spirit would move him to say the oracles that are then recorded. But somehow he becomes really almost taken over by the spirit at that point, which foreshadows what I was talking about yesterday and a little bit this morning about how the spirit comes in, gives a new heart and a new spirit to the individual. and almost seems to take away free will in a sense, that the power of God is so strong there that it's guiding the person. Same spirit that lifted up these statue-like bone figures that had been reconstructed in Ezekiel 37. So, the spirit, so important in the history of salvation then, which, when we get to Paul, it becomes a reality that is even more central, I think.

[12:33]

So, when we talk about our baptism, as baptized Christians, we're ones that we've been hearing in our Gospels, particularly in these last two, three Sundays, about once the the disciples are baptized, they go forth and they're to proclaim and bear witness to Christ. And clearly, the reason that they're able to do it is not because they're eloquent, it's not because they've learned a lot of clever ways to communicate this, but the convincing dimension of what they're doing is whether God is present with them. And that presence is in the form of the Spirit. And when we all think back on our own faith journey, probably baptized as infants, didn't have much to do with this. But in reflection back on this, we're seeing that that Spirit which was operative in our families, and in the parish faith communities, etc., that that spirit was shaping us and nurturing us along on this journey.

[13:43]

And So, if we can talk about our lives at this point as bearing witness, having a symbolic character that points to God being active in our lives, it's clearly because of what God has done through the presence of the Spirit. And the way that this gets nurtured, of course, we think the rites of initiation, you get baptized and then you probably Liturgists tell us we should be confirmed then, and then we receive the Eucharist. So we're baptized, the water, the Spirit comes on us in confirmation, but then we go to the table and we think of the whole Eucharistic action, the Epiclesis and the Eucharistic prayer in which the Spirit changes the forms of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, then we eat that. And from earliest Christian times, we become like what we eat.

[14:44]

And so, the Eucharist, in consuming Christ, we're trying to become like Christ. And obviously, you know, when we consume the Eucharist, the real presence is there, but it's not a sort of mundane kind of literalism in which we're eating heart of Christ, arm, leg, whatever, but the presence is very real. And how do we talk about that holy that's there? We're saying that it's not a mere symbol, it's not a mere metaphor, and so if we take it then, literally we're eating part of Christ. But then we say, well, that's not quite right. And then we say, well, it's not just a sign. It's not just a symbol of what Christ is like, which would then be, well, it's the bread and wine are really figurative. They're pointing towards Christ. So, one of the things that's helped me in recently thinking about this is that between the literal and the figurative, that somehow this reality of the numinous, the holy, the spirit world, there's something different there in which it's, there's an actual

[16:01]

participation. There's an actual reality there that it's different than the simple literal, but it's not just simply figurative. So if we can think of the holy in that way, One of our older monks, he died probably about five years ago, and very well known as a liturgist, patristic scholar, Father Godfrey Dieckmann, very vivacious character. But in his last, he taught until he was about 86. And the last 15 years of his teaching, he said, You know, really, one of the themes that I kept hammering home over and over and over again is when we hear that phrase that we are children of God, he says, he would accent the R in that. He says we are children of God. It's not just simply a way of talking about us, but he's almost saying that almost on an ontological level that we're in our terms of our being, that we've been lifted up and transformed.

[17:12]

We clearly don't become like God the Father, but we do become conformed to Christ. and we're on the – so we're somehow brought into the life of the Trinity at that point. And I think he wanted – he spent a lot of time dealing with the early first two centuries were his favorite area. But he kept saying, he says, I'm amazed, when he kept looking back over his years of studying this, that the incarnation is the thing that is really more important for them even than the resurrection. And so, in some way, this reality of Christ becoming like us, so that we might become like Christ, that God becomes like us, that we might become like God, not to displace God, but to be conformed and participating in the reality of God. Somehow, when we think about the holy being with us, But that's what has to be going on here.

[18:16]

So when you talk about the dynamic character of the Spirit, how is that Spirit that we receive at baptism that then quietly moves in our depths, changes us over the years, and makes us more and more into those children of God that God has promised us to be. The Eastern church talks about this as deification or theosis. The Western church, whether it was because of a a very pronounced emphasis on original sin or a more pessimistic anthropology didn't emphasize this dimension of how we become godlike. So that's why we participate in these sacraments and these mysteries is that we're to be conformed and we're to be brought into this this divine life and to be divinized in the process.

[19:21]

So, when we read Paul's letter to the Romans, chapter 8 is his key, at least it stands out, it's the summarizing chapter, and I would say it's probably the peak that whole letter is one that Richard Dillon teaches at Fordham, a wonderful teacher of Paul. But he says every time he teaches Paul, it's like climbing Mount Everest. And if that's the case, then I would say that by the time you get to chapter 8, you're up there in real thin air at that point in terms of what it's like. But chapter 8, it talks about the battle, the first part of it. It talks about the battle that's waged between the spirit and the flesh. In academic commentaries on this, typically what they say the flesh is, is its self-centered existence, which I think is probably right, but I often wonder if that's incarnate enough.

[20:23]

It almost seems like an idea. But nevertheless, I think they're on the right track because it is self-centered, ego-centered. It's an active kind of understanding of what flesh would be like here. So one who lives in order to get the most out of life for oneself, or one who lives in order, I got to survive, would according to this definition be living outside the realm of the spirit and in the realm of the flesh. You can't, you can't both, they're, They're waging a battle inside of us, but they're antithetical. You make a decision for one or the other, but it's a fundamental decision that each of us makes repeatedly. You know, we can't just do it once and then it's settled. But it's rather this kind of battle between the ego and the spirit is one that we experience over and over again. And I suppose we experience that in terms of the paradox of the cross.

[21:27]

Life comes out of death to oneself is a stance that is paradoxical, which means that it doesn't conform to common sense. something that seems, we can understand it, but it doesn't conform to the way we think of life as being put together in a rational or reasonable way. So, the cross, where will we meet that? I'll quote Godfrey again. In my first course from him, way, way back, 25 years ago, he was saying, whenever you get close to contradiction or to paradox, you're probably coming pretty close to the truth. So it makes you think about that. When things don't quite fit together, maybe it's a paradoxical, profound truth. From a Christian perspective, reason gains its true character, a character that was weakened by the sin in the Garden of Eden through the grounding of the Spirit.

[22:36]

In other words, I think the Spirit coming back to us puts us on a new ground so that then our powers of reason can operate. So faith would precede reason, and it puts us in a place where we can then but reason along and make good judgments as a consequence. This chapter 8, it comes in a sequence obviously right after 7, but if you recall 7, that's where Paul gets into this very introspective sense about, he's almost in the depths of despair because he knows that as much as he wants to do the good, For some reason, there's something that's inside of him that makes him do what he'd rather not do. And he ascribes that then to the power of sin. He almost mythologizes this power at that point. But I think he does this introspectively, but probably his meditation there is

[23:41]

preparing the way for him then to say why the Spirit is so important, is that we really can't save ourselves and that we know this in our own struggle to live according to what God is calling us. We can't fulfill the dictates of the law all on our own, but God is the one who then rescues us. And this As you move then back into chapter 8, you move along, you get to that wonderful section where he talks about we don't know how to pray as we ought. But this all gets settled, he says, because in the same way, the Spirit also comes to help us, weak as we are. So we do not know how to pray. The Spirit himself pleads with God for us in groans that words cannot express. And God, who sees into our hearts, knows what the thought of the Spirit is. And because the Spirit pleads with God on behalf of his people and in accordance with his will."

[24:46]

So when you start talking about living according to hope, And, which is, as we know, is really important in that chapter. That hope is based upon what God is actually doing within us. And there's, so there's much more going on when we pray than what we're aware of. If we pray the psalms, it's clearly it's good to be attentive to the words and the message that each psalm unfolds, but inevitably we're going to zone out at some point, we're going to be preoccupied, we're going to say these things and have to get done, which psalm did I pray? In some ways this comes along, but I think the consolation here is that by being there and by praying these and being carried along with the community, that there's something going on inside of us that we're not even fully aware of at that point.

[25:50]

One of our fellow that was led our ecumenical institute, he was talking about a fellow that had somehow his life just collapsed. And he couldn't get himself to pray. There was just nothing he could do. But this is a guy that was pretty well advanced in the spiritual life. And his bottom line was recognizing how he just did not have the energy. But he was saying that the community, he was Protestant, so it was his faith community that he was ministering to. He says, don't carry me. And I think there's some real truth to that, that the Spirit, wherever we're at in our journey, the Spirit is there working in ways that we're not even fully conscious of. Our responsibility in prayer is to discipline ourselves to carry on the dialogue and to try to make ourselves as receptive as possible to what God is telling us in this dialogue.

[26:56]

When we enter into conversation with someone, whether they're right next to us or whether perhaps if they're on the phone, this is the conversation that really captures our, takes our focus. We put our attentiveness on the other. And I think dialogue then is really at the very heart of our faith. It clearly, when you start trying to make sense out of the Old Testament, it is the dialogue with God that goes on from the very beginning that is the governing center of what's there. We talk about the covenant, but it's a covenant that's sustained by the conversation and the dialogue that goes on between God and the people. And to me, it makes – it's most profound when you get in – I've been talking a lot about the tragedy of the exile, and the confusion, not being able to make sense out of that. Ezekiel came in because he had a certain agenda in which he wanted the people to

[27:59]

to stand up and take responsibility, he says, you're responsible for this. Another voice that came in was the Deuteronomist, which they edited the books that you have from Joshua up through 2 Kings. But what's very typical in their understanding of how God operates is a very simple, simplistic formula, which is pragmatic, and I think we live by it. If you do good, you get rewarded. If you don't, you get punished. But it tries to explain everything by this, all of the ups and downs of Israel's history. And you know, it may do something in terms of bringing a certain amount of clarity, but it leaves you wondering. Job certainly doesn't buy it. and he's left on the outside of that. So, if we take a step towards what Job is doing, and I think this comes closer to what the Old Testament really is encouraging us to do, is that if we try to understand how God is operating in our lives, what God is doing is trying to keep us in conversation with him.

[29:11]

And he's going to do whatever he can to make sure that we keep working at that kind of conversation. And so if we can keep the dialogue alive, we end up being on track. And how that responds to that crisis of the exile, I think Job's response to an experience like that is that he cries out. And when you cry out, you don't pretend to have an answer. The Deuteronomist pretended to have an answer. He said, you did something wrong. Well, Job's so-called friends were trying to tell him, well, you did something to cause all of this, the bad things that were happening to you. At the very end, Job's friends get judged by God as being too harsh or off track. And the one who rises up in this is Job, who was in conversation. And so, I think there's something about that. And because our lives are really focused and we dedicate ourselves to prayer, I find it very encouraging to see that at the very heart of the scriptures

[30:19]

clearly throughout the Old Testament and I think carrying on into the New Testament is that effort to try and keep us in conversation with God. And the more we can stay with that, then we're on track. And Paul's message in the Romans 8 is that that conversation is going to be sustained by God's action. He's not going to just leave us on our own to try and do this. So, there's much reason for hope in this. One of my confers a while ago talked about, he says, you know, it's really important that we all be faithful to Lectio, and there's so many ways that this gets eroded. It can get edged out here and there, you've got to do this, that's more pressing, that's more practical. But his point was, is that when I do this, it's not just for my own advantage, but it really has an impact on the others that I live with.

[31:23]

So, actually doing Lectio personal prayer is not just private, but it is an act of concern, generosity, also towards the others that I live with. And I think it's a way that the more we're attentive to that, and attentive to God and allowing God to work in us, that it's going to have an impact in visible and probably a lot of hidden ways on the quality of our life. I often, since I do academic work most of the time, I romanticize at this point manual labor. If my hands were free, I could say the Jesus prayer all the time, and I know it's not that easy. And I think back when I did do manual labor back in high school and in college, and I had this job that was in a hog slaughtering plant of all places.

[32:26]

And you'd get up on a line where all the carcasses would go by, one after another. And this place was trying to make money, so they would make them go faster. They'd go by you. But you'd get, you know, it seemed like thousands of these things would go by each day. Fortunately, I had a job where all I had to do was wash the blood out of the neck of the carcass. And it was easy, a little machine. There were some that were really tough, where you had to be really strong to do these jobs. But I think now, reflecting back on this, well, if I had known something about this the Jesus prayer or forms of prayer like Cassian was talking about, it might have helped me zone out while I was there doing this and I could have been in a different, which seems to be the logic of basket weaving in the desert, isn't it? That they did this so that their minds could actually be, they're more praying than they're working, but I don't know. Anyway, but these kinds of prayer are so important.

[33:28]

And as we're reading now, as your table reading, coming up with the Jesus Prayer and how important that is, certainly it's very important in the Eastern Orthodox tradition. Callistus Ware, Anglican, I think Benedictine, he came to our place, gave a retreat about five, six years ago. But his whole his whole retreat was, Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. And then he unfolded that. It works. There's richness there in that. But a prayer that is really central within the Eastern tradition, which I think has made considerable inroads within monastic circles in the last 20, 30 years, at least to my knowledge anyway, So, Cassian, of course, is one who has a high regard for this kind of prayer that will keep us connected with God.

[34:36]

So, repetitive prayer like, Oh God, come to my assistance. Lord, make haste to help me, saying that over and over and over again. So, I would like to conclude with a prayer that Cassian has, which he uses language that's close to the chapter 17 of the Gospel of John, Jesus' high priestly prayer. When all love, all desire, all effort, all inclination, all our thought, all that we live, that we speak, that we breathe, will be God, and that unity that now is the fathers with the sons, and the sons with the father, will be poured into our perception and our mind, so that just as God loves us with sincere and pure and indissoluble love, we may be bound to God with perpetual and inseparable love, joined to Him in such a way that whatever we breathe, whatever we know, and whatever we speak would be God.

[35:44]

Our help is in the name of the Lord. This final talk is on the already but not yet and the status of the monk on the spiritual journey. It's easy to talk about the already but not yet, but it's quite another thing to live within its tension. For we can feel stymied and frustrated by a lack of opportunity or resources or of relationships. We hear people tell us that the real test of character is how you handle disappointment. I think Jesus had these in mind, these kinds of experiences of an aching absence in our hearts when he preached the Beatitudes. In the version that occurs in Matthew chapter 5, we hear Jesus repeatedly say, happy or blessed are you. And then he goes on to describe a situation that we would see is only partially fulfilled or is lacking something essential.

[36:51]

One of my colleagues noted recently that he gets quite a different sense from the translation of makarioi as happy. rather than translating it as blessed. For blessed gave him a sense that it's more static and thing-like. It's something, you bless metals, you don't bless pain. So when we use the translation happy, I think the paradox in these beatitudes comes through much more clearly. Happy are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Happy are they who mourn, for they will be comforted. These conditions of being poor in spirit or mourning are ones that most of us would like to avoid, or if they come, we want to move through them pretty quickly. In ancient Israel, mourning rites extended usually for about seven days. It gave what they were designed for, of course, was to affect the separation, but it also gave them time, a sort of time out for the family in which they could grieve and be together.

[38:05]

But once the seven-day time was over, they were to wash, eat, have this meal, and then go back to ordinary life. This was a time of, when you're mourning, it was a liminal or an in-between time. Once it's completed, then you go back. But there's a story in the ancient Near Eastern literature about a vigorous protest against death, and it's in the Epic of Gilgamesh. And Gilgamesh had this, as the story goes on, he got this very good friend, Enkidu, And they were warriors, they went on adventures, and they became very good friends. But in one of their adventures, they overstepped the boundaries to where God says, one of you has to pay for this. And so, Enkidu is doomed to die. And when he does die, the ripping away of Enkidu from Gilgamesh leaves this

[39:06]

emptiness in Gilgamesh's life. But the way Gilgamesh responds to it is that he is determined at that point that he's going to try and find a way to get out of dying and to transcend death. So, what we see is he stays in this time of mourning. He goes out into the wilderness. He puts on a lion skin. He begins traveling and He's trying to find this key. How can I get out of dying? And we hear the story then of him going across the sea, which includes what they call the lethal water. So if anybody touched him, they would die. But he goes through this, gets on the other side, and he runs into a character called Utnapishtim, who is the counterpart of the biblical Noah. And he's a human being, but he actually is immortal, because he had gotten on the ark, he survived the flood, and at that point, the chief god Enki says, well, he's made it at this point, so we have to let him live on.

[40:12]

So he's living on at this far reaches, way beyond the edge of the cosmos. And so, you find Gilgamesh trying to avoid death, and he meets up with this character, And Utnapishtim then becomes the wisdom figure, and he wonders, why are you here? What are you doing? And he says, you know that your role back home was to be the leader of your community. You were the king of Uruk. And the way kings typically operate is they're paying attention to their people and they're promoting justice. They're trying to build up the community so that it lives on. And he says, here you are, you're out pursuing your own anxiety, your own worry about And he says, if you're really searching for immortality, the kind of immortality you need is to be back there conscientiously carrying out your role.

[41:14]

And one way would be to build up the wall of Sipar, because the wall would have been a symbol of the city. It would have obviously lived on long after him. But so Gilgamesh gets this counsel and advice from Utnapishtim. But as Utnapishtim sends him back, he says, but take this plant. And it's kind of like the magic plant. You eat this and you would probably live on. And so as he's making his way back home, he stops at this watering place, he gets some water, he dips to take a bath at that point. And as he's down in the water, this snake comes out and eats the plant. And he's lost without it at that point. And it's kind of a sidebar to the whole story. But then, of course, it explains why They thought of snakes as being kind of immortal. They would shed their skin, come back next year and shed it over again.

[42:18]

So the snake makes off with this rejuvenation that was part of the plant, but Gilgamesh then goes back and to his credit then he goes back and he takes up his role in the city of Uruk and he recognizes that to be human means to have limits and that it's best to try and live as best as we can and as uprightly as we can within the human condition. I think all of us at times have had yearning for completeness in this life like Gilgamesh. And so we're challenged by Jesus's words that happy or blessed are ones who seem a bit down, or who seem to be aware of what they're lacking, and they're mourning this deficit in life. So Jesus' words, happy are those who mourn, or happy are those who are poor in spirit, they obviously are paradoxical to us.

[43:21]

And we wonder, what does he really mean? For the literal truth doesn't seem to be right. But how much different I would ask then, is Jesus' advice here that go back, live within these conditions? How much different would it have been from that ancient Mesopotamian sage Utnapishtim who said, go back, find your fullness in life by living under these conditions? So, if we assume that Gilgamesh, this king, returned and he ruled diligently, that he probably was going to run into many problems that would be intractable, that would cause him a lot of stress and a lot of anxiety. And so, I think an analogy in our present day, we can look towards abbots, priors, college presidents, pastors, heads of organizations and they're all leaders who are going to run into problems either with personnel or resources and they're probably going to have a lot of sleepless nights and they're going to get ulcers over this.

[44:29]

And there are instances in which these are people that we would regard, well, they've got power. They have more power than the average run of people and they have a certain amount of privilege. And why would we call them being poor in spirit? But I would suggest that many of them probably carry a pretty heavy load of their responsibilities. So you wonder then if they hear the beatitude. blessed are those who are poor in spirit. It must mean that it would be a kind of encouragement to stay with the issues and try to do as best as possible, knowing that the outcome is going to be less than perfect, and you're going to end up living with that partial kind of situation in which there's still something to be accomplished. Those who do everything possible to reach perfect fulfillment in the here and now are probably the kind of leaders that are going to end up causing a lot of trouble for themselves and a lot of trouble for the people around them.

[45:40]

And we know the wisdom that comes out of the rule where Benedict says, superiors should be careful in trying to remove the rust from the vessel, lest they break the vessel itself, or they should be careful in urging the flock on, that they don't drive the flock too much, overdo it, and make them collapse in the process. So extreme measures, which try to reach this kind of perfection, they seem to be more the ideas, the programs, the work of human hands, and they end up distancing us from what probably God has in mind for us. So if we continue on then with the Beatitudes, Jesus says, blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth. And the meek then would be ones who travel pretty lightly on the earth. They don't overinvest in work or symbols of power. To do so means that such goods and symbols must be defended.

[46:44]

If you overinvest in them, you end up having to defend them because it becomes so much a part of one's own identity. And as I've mentioned a number of times, which is probably my own fault, or what I struggle with in life, is trying to keep together an honest approach to the monastic vocation, and yet being in sort of a professional track in which you're responding to all of these expectations in the educational field. And so you find yourself marching to two different sets of expectations. As you can expect, probably if you get your wage out of the professional side, those things are going to end up carrying a lot of weight and it takes tremendous amount of counter pressure to balance that off. But it is however any one of us finds that kind of tension.

[47:46]

It really is important, I think, to hear this beatitude, which says that Happy will those be who are meek, who seem to step back and they have a little sense of distance from things that are really good and important in life, the way they serve others, the way they find a certain amount of joy in that service. All of those things are good. but somehow to see my own identity as a follower of Christ is not caught up in what I do, but rather in that following. So, we need to hear these words of Jesus, blessed are the meek. It's not the winners by worldly standards who come to inherit the earth. But it's the ones who recognize that their true status as wayfarers on the Earth are ones who are privileged to use this planet and its opportunities for a time, and then accept the fact they move on and hand it on to others.

[49:01]

It's important then to tread lightly on the earth. And I think we can live with a passionate commitment, but yet do so with a kind of larger vision that allows us to follow this example of the meek. In one of my classes, we were reading a work by the political philosopher Hannah Arendt, and she made the point that humans who do not strive for immortality will settle for living at the level of the beast. And it seemed to me that this exhortation made a lot of sense. If you don't have some ideals or goals, that we probably won't grow very much. We won't stretch ourselves. But as I went through this, one of my students said that she found Arendt's exhortation depressing. And I asked her, why do you find that? And she says, well, because the bar is set so high, striving for immortality.

[50:03]

And she was saying, it's almost, it seems impossible, and therefore you're almost setting yourself up for failure. And it would be better to take a bit more moderate road in this. And so when I hear Jesus telling us, blessed are the poor in spirit, and blessed are the meek for both the kingdom of heaven and the earth will be given to them. I wonder then, when I hear this, if my student's instincts were probably a bit more on track and her heart was in the right place. Enduring life is not something, enduring life or the immortality that aren't talked about, it's not something that we do, but rather it's given to us. And if we keep in mind that it is given, then how much else, how are we going to use our energies in the way we reach out to others? We probably will do it quite differently. Jesus then continues on with his Beatitudes by saying, blessed are they who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be satisfied.

[51:12]

Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy. We readily hunger At least in many cases, I think because when we feel vulnerable, we hunger and thirst for a bit more control, a bit more power. And even if we want this power only to defend our freedom, it still is an effort directed at securing oneself. Things are going well for me. This often means that pieces are falling into place as I planned it. But Jesus challenges us to have a bigger picture of what we long for. It should not just be what I have planned for that I long for, but I should long for those things to fall into the place as the Creator intended. My memories of my grandfather create for me a picture of one whom I've, he died about 30 years ago, but he creates a picture for me of one who's kind of the salt of the earth.

[52:15]

He was a guy that, he lost his farm back in the Depression, and then he went on to raise a family of 10. And he did this working as a farm laborer. He was conscientious about this, but obviously, if you do that form of work, you're not gonna be terribly ambitious. But all of my impressions of that family, I only got to, I was with them, at least knowing them for the last 10 years of their life, my grandparents. It was a really a happy family. And I recall on some instances he talked about how he had a conflict with the farmer that he worked for. or some other authority figure, and he made the comment, but that's just not right. And it always struck me he had a strength of conviction, that he really knew that there was an ethical world order, which I think comes from people that work close to the earth and they have their feet on the ground and are not real ambitious, but they know when things are in right place.

[53:27]

And he would stand up for that. So he was not a guy that you would say, well, he would engage in sort of peace activism or be someone who is passionately committed to social justice issues, but rather his role in life was was to live in this sort of humble profession and be deeply committed to what was right. Because he just didn't stand up for what was right for him, but if it wasn't right for someone else, he would speak up about it. Which, in retrospect, and as I reflect back on that, that took a lot of strength of character, which I was too young to catch on to at that point. But he once told me, he said, you know, the monks are the ones who have it right. And then he went, it was probably about three or four years before he died, he was visiting one of my aunts who lived in the Twin Cities.

[54:29]

So he went out and he visited St. John's and he went out and visited and he came back and he says, God, I saw your place. You know, I could tell, I could read on, he was, it's fine, but he was not overly impressed with that, even though he's talked about how monks have, and I never talked to him about it, I sort of carried this around wondering what his assessment was. But as I move on, I think his point was, is there, there probably was a bit too much showiness. The buildings were a bit too big. There was perhaps too much wealth that he saw coming through in the place. And for him, I think his idea of monastic life was one that was really close to the earth and really quite simple. He was, in some ways, he was a guy that I remember in the last couple of years of his life, I was always stunned by this relative would come up to him and say, well, be sure to pray for me on this.

[55:36]

And so he was noted as having kind of this hotline to heaven or whatever. And so he would, clearly, when I think back on it, he was living as a monk. He'd simply lived a very simple kind of life, prayer was very important to him, and he was looking out for others, I think, in those ways. we probably have monasticism in a lot of places, we often don't quite look for it in ways. So, continuing with the Beatitudes, Jesus said, blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God. In the gospel story of Martha and Mary, when Martha complains that Mary has left her to do all of the household chores, Jesus counseled Martha, Martha, Martha, you are worried and distracted by many things.

[56:39]

There is need of only one thing, and Mary has chosen the better part, which will not be taken away from her. And so, clearly the bottom line of this story is paying attention to this one thing necessary is what Jesus means by purity of heart. And in Benedict's terms, I guess it's that rule, the line in the rule which says, prefer nothing to the love of Christ. So if the love of Christ is our number one desire, then all of the other very important parts of our life will fall into their proper place. It's our relationships with others, our concern about work, concern about the future, etc. If we yearn then for God above all things, then God's presence in the people around us, in the beauty of creation, and his presence even in the midst of disaster will be more apparent to us. And it's the same point that you find in the Old Testament in the Shema, in the book of Deuteronomy chapter 6.

[57:45]

You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might." The first part of the greatest commandment that Jesus also teaches. This promise of being ones who see God will not simply be the beatific vision after the earthly life is completed, but it will also be a greater awareness of God who is the one in whom we live and move and have our being. And so, in concluding the Beatitudes, Jesus says, blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. Blessed are they who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when they insult you and persecute you and utter every kind of evil against you falsely because of me. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward will be great in heaven.

[58:49]

We know that there cannot be peace without justice. If we have injured someone or something of that sort without proper restitution, there won't be any healing and there won't be any reconciliation. So the peacemaker is the one who gets out there and strives for this kind of healing and restoration. And when things have returned to their right order, then there will be peace. Those who hunger and thirst for the right order are ones who are going to encounter much resistance from those who are invested in the status quo and who believe they will be diminished by attending to past misfortunes. But the peacemaker is persistent and does not rest until this justice is done. But at the same time, the peacemaker will be one who tempers his activities with the realization that the final banishment of oppression and the complete healing of all illnesses and the full experience of peace and justice must await the return of Jesus at the end of time.

[60:06]

If we are ones who are challenged by peacemakers to rectify a wrong, we too need to be mindful that what we are invested in, our institutions perhaps, careers maybe, that these things are not ultimates. They're not to be defended at all costs. And that the only cause that we can throw ourselves into completely, that we would sort of lie down in front of traffic for, would be the following of Christ. And so, I often think about the, you see these suicide bombers, very tragic in the Middle East, and that what is it that drove them to do that? And obviously, they're at a point of extraordinarily desperation. You know, you see these young kids, not just young men, but young women who go in and blow themselves up for this. I think they're getting a promise of the way Islamic tradition would understand a martyrdom, but it really is a political martyrdom rather than a martyrdom as we understand it within Christianity, because obviously martyrs in the early church and martyrs in our own time don't choose it.

[61:23]

something that happens to them, which in this case, at least it seems that from, at least from looking at it from the outside, it seems like this political freedom has become an ultimate for them. But I say this at the same time with a lot of hesitation because of the real desperation that I think a lot of these communities have found themselves in. It's just tragic of what they go through. But when we think about poverty and simplicity of life, we may often think about the challenge of not being able to call our own shots or being curtailed in the things that we can do. But Jesus tells us that through the Beatitudes, that we are blessed or happy because of this. We are in a good place even when we're not fully aware of it.

[62:25]

We're poised at this time to see God and to enter into his kingdom and even to inherit the earth. Fortunately, in following Jesus, it's not all delayed gratification. There is a partial fulfillment as we walk along in this journey. we can share Mary's devotion to the Lord and experience his presence with us as we strive to do what is right for others and to be detached from status and power. One of our young monks who was in temporary bowels, he's since left, but he was wrestling with monastic vocation. And in our place, the question that he raised was one that really caught me off guard, is he thought our way of life was too easy. not being in control of one's life, you have obedience, you don't have all your resources. If you want something, a lot of times you have to go and ask for this.

[63:27]

And I wondered, but for him, as he looked at this, and he had a real commitment to helping out the disadvantaged or the underprivileged. And I think he saw a real rhythm harmony, and joy that was coming through in living in the monastic life. And from that point, he ended up leaving. The reason was he wanted to get married, so it didn't end up being that. But his questions, I thought, were really challenging and thought-provoking, for they made me think of how privileged my way of life is, and how much my own struggles that I think of in terms of conversion of life or finding balance in life, that a lot of these things probably arise just out of my own I cause them, rather than the circumstances around me. So when we embrace this situation of the already but not yet, we will live as stewards of a creation who rule over this creation, I think, with a certain amount of care and reverence.

[64:39]

We will be accomplishing things that old Utnapishtim was trying to get Gilgamesh to do, When we do so, I think we become the salt of the earth and the light of the world, and our lives will be strong testimony to onlookers of the presence of Christ who's active and alive within and among us, and we become genuine symbols that God is here and God is alive with us. So I'd like to conclude with the following prayer. O Lord my God, the world is yours and everything in it is yours. Help us to look beyond our own preoccupations and concerns and learn to love the world as you love it. Where there is hatred, let us so love, and where there is injury, pardon. Where there is doubt, faith.

[65:41]

Where there is despair, hope. Where there is darkness, light. And where there is sadness, joy. Help us, O Lord, to see you in the people, the events, and the things of daily life. We make this prayer in Jesus' name, both now and forever. The status of the monk on the spiritual journey? Yeah.

[66:18]

@Transcribed_v004

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ