You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Trinitarian Wisdom from Early Church Fathers

The talk examines the theological contributions of key figures like Cyril of Alexandria, Gregory of Nazianzus, and the Cappadocian Fathers, emphasizing the development of Nicene theology and the doctrine of the Trinity. The speaker illustrates the historical context and evolving theological debates, particularly focusing on the Arian controversy and the shift toward a more structured Christian humanism informed by Greek culture. Special attention is given to Gregory of Nazianzus's efforts to articulate a nuanced understanding of the Trinity, promoting a distinct but unified conception of God. The trajectory from the era of Constantine to the time of Theodosius is also highlighted, underscoring the ecclesiastical and political dynamics that shaped early Christian doctrine.

Referenced Works and Figures:

- Cyril of Alexandria: Discussed for his interpretation of Israel's wanderings in the desert as an allegory for spiritual growth and union with God, contributing to the Alexandrian tradition of typological readings of scripture.

- Nicene Creed: Described as a pivotal text developed during the First Council of Nicaea, addressing the Arian controversy by affirming the divinity of Christ as consubstantial with the Father.

- Athanasius of Alexandria: Noted for defending Nicene theology against Arianism, advocating for the consubstantiality of Christ with the Father as essential for salvation.

- Cappadocian Fathers: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus worked to develop the doctrine of the Trinity, distinguishing the three persons without compromising the unity of God.

- Gregory of Nazianzus: Explored as a central figure in articulating Trinitarian theology, known for the theological orations that emphasize spiritual maturity as prerequisite for theological discourse.

- Oration 25 and Five Theological Orations: Referenced as Gregory's efforts to explicate the Trinity, emphasizing the distinct roles and relations of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit within the divine essence.

AI Suggested Title: Trinitarian Wisdom from Early Church Fathers

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

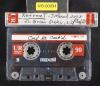

Speaker: Fr. Brian Daley, SJ

Additional text: Conference III

@AI-Vision_v002

the way through the desert and the stations of the people of Israel in the desert. The patristic text was by Cyril of Alexandria, but it was clearly so that Israel's wandering in the desert, he doesn't mention the 42 stations in the desert by name but he does suggest that all the places that they went and their stopping and starting was guided by the cloud that led them and guided by the presence of God and that reveals to us a kind of growth in union with God being led by the Spirit of God to the promised land and so there is this tendency I think especially in the Alexandrian tradition, to see the stories of the New Testament, especially the big ones, like the story of the Exodus and the story of David and so on, as having a deeper meaning that relates to Christ and then to the life of the Church and to the Christian life. And this wasn't to say that it didn't happen, but that there's also something in it for us.

[01:03]

which of course is central to the Christian liturgy, the Western liturgy as well. Our first reading is chosen to kind of echo the gospel because the church sees anticipations of the gospel in the Old Testament. In our baptismal liturgy in Easter night, there's all the allusions to the Exodus and the Red Sea because this was seen as kind of pointing to participation in the mystery of the pastoral transfiguration, the death and resurrection of Jesus. So I think these ways of looking at the text really had fed into the life of the church and picked up also on Jewish approaches to the Bible that were already current before the Christian era, seeing in the text also something about us. Anyway, today I wanted to to talk a couple of times about Gregory of Nazianzus, maybe somebody who's not as much talked about in our Western tradition, and yet somebody who is very central to the development of Christian thought and spirituality, and who's a fascinating character in his own right.

[02:14]

I got interested in Gregory of Nazianzus a number of years ago and did a book with translations of a number of his works, an introduction, which got me very fascinated by him. Because in Gregory of Nazianzus, late 4th, second half of the 4th century, I think you see a phenomenon that is also flowering in other parts of the Church with other major figures, like his friend Gregory of Nyssa, like St. Ambrose, St. Augustine in the West, And that's what I would call Christian humanism. People who for the first time are not only extremely intellectual, as Origen is, and highly educated in their own field, but who really feel at home in the whole Greek culture of their time, the whole Mediterranean culture, and see it as a gift of God or something that's given to us for the flourishing of the church. And so we see, I think, in the late 4th century, a kind of a movement to bring together Greek literary traditions,

[03:19]

and poetic forms, Greek philosophy, Greek art, sculpture, we don't know much about music at the time, but that was probably involved, and the Gospels, and the whole Bible in fact, and to form out of them really a new center of a Christian Greek culture, which in effect became the standard through the West, through the Middle Ages, and in the East as well. Just a little bit of history to kind of set the background for this. As you remember, with the reign of Constantine in the early fourth century, the Roman Empire very quickly was transformed from being an environment that was hostile to Christianity, at least officially, to a friendly, welcoming, and ultimately supportive Christian state. Constantine was emperor in the Roman Empire from 312 to 337.

[04:24]

His father had been the emperor before him. His mother was a Christian and was very interested in the welfare of the church. So Constantine knew about Christianity and was probably favorably disposed towards it since his childhood. And when he gained control of the power structures, more or less decisively, in 313, he issued his famous edict offering freedom of worship to everybody in the empire. But this meant, in effect, the beginning of a certain favoritism shown towards the Christian community. The Romans were always interested in uniformity, like any big centralized imperial government, like the Soviets or China today. The Romans wanted everybody on the same page as much as possible, not only as far as keeping the laws and paying their taxes, but culturally and linguistically and every other way. And so a lot of the emperors in the third century were very threatened by the idea of religious pluralism and all the different sects, and especially the Christian community, which was growing fast and growing more intellectual.

[05:35]

So in the late third century, the time of Diocletian, the reforming emperor, who was trying to get hold of everything, there was real persecution, really for the first time. And a lot of the martyrs that we celebrate were put to death right at the end of that period of persecution under Diocletian in the 290s and early 300s. Constantine seems to have seen that that was a losing battle, and also to have been favorably disposed to as Christian, so he offers general freedom of worship, and within a few years began supporting Christians in a number of ways, subsidizing the bishops when they were traveling to bishop's meetings directly, letting them travel in the official mail coaches, and also paying for the building of purpose-built churches for the first time. Before this, it seems the Christians gathered in private houses or halls. Now they began building buildings for worship, which they called basilicas, which is the name for a law court.

[06:39]

They were modeled on the way that a Roman law court was built, in a sort of long rectangular shape with an apse at one end and a pointy roof. But they were built as a place for gathering for the Eucharist and for teaching. And Constantine funded these in Rome and Jerusalem, in Constantinople, and a number of the other major cities. He was interested in Christian theology, and certainly read a lot of it, although he also kept up an interest in other religious traditions, and was only baptized on his deathbed in 337. He was baptized at Easter and died at Pentecost, because he knew that he was ill. But he was interested throughout much of his career in promoting uniformity or unity or consensus in the Christian community as well as in the rest of the world. And so he was worried too, not so much now about deviant religions, but about conflicts within the Christian community, about struggles for orthodoxy.

[07:41]

The time of Constantine was a time really of the first major struggle that we know of, not the first, at all, but the first really worldwide struggle about Christian doctrine and Christian teaching. And this was the so-called Aryan controversy, the struggle about the person of Christ, and in what sense we want to see Jesus as divine savior, as a divine person. Arius was a priest from Alexandria, and by the time of Constantine was elderly, I think, within his 60s, at least. A very successful priest, he was a great preacher, had a great following, especially among monastic women. He wrote songs, apparently, kind of popular songs, a particular thing. He was kind of the magnetic figure of Alexandria in the time. But his approach to the person of Christ was, in fact, an old traditional one. that Christ represented a kind of connecting link between an unknowable God and the world of creative beings and creative intelligences.

[08:48]

So that Christ kind of was the first of all creatures to be produced by the unknown God, and in turn then became the instrument of creating the rest of the world. That was an idea that had been tried before. In some ways it reflects a kind of an exaggerated version of Originism. But Arius began pushing this as the only way to think of Christ in his relationship to the Father. He had a strong vision of the unity of God, so we can't say Christ is God in the same sense as the God of Israel. And also a sense of the meaning of generation, the sonship of Christ. If he's a son of the Father, in a real sense, then he must be produced, because every son or daughter is produced, generated. So we have to say that God brought Christ first into being and then through him others. And he even popularized slogans, as we know, like, there was when he was not, there was a once when he was not, there was a point at which there was no son.

[09:53]

Otherwise, he would be equal to the father or simply a part of the same divine substance. Other people saw this as a threat to our faith in Jesus as a divine savior, as communicating divine light to the world. And people were shocked by the kind of in-your-face explicitness of Arius' presentation of this approach to things. So a division began to grow up. Arius and his followers saying that people like the Bishop of Alexandria, Alexander, really made no hard distinction between the God of Israel and Jesus of Nazareth. And in doing that, they weren't really able to speak about Jesus as relating to God, as calling God as Father. It seemed to be simply a way of saying, now he appears as the God of Israel, now he appears as Jesus of Nazareth, the Son. And that seemed to empty the whole notion of salvation.

[10:57]

But those who attacked Arius felt that he was simply reducing Christ to a creature however exalted to still being one of us and therefore unable to save us. Yeah? Well, that's a good question. I think, basically, transformation, communication of the life of God to us through Christ in the power of the Holy Spirit. So, I mean, I think in the West, since the Reformation, we tend to think of it more as a kind of a relationship to the Father, kind of a Lutheran understanding, which is pretty general, that somehow we were in a bad relationship to God and now we're in a good relationship to God, we're justified. But I think in the early church, most people thought of it in a way much more deftly than that, as including sanctification. And ultimately, as the Greeks would say, divination. That we're communicated a share in the very life of God, which doesn't make us into parts of God.

[12:01]

But it makes us divine beings. It enables us to live forever, to live in unity with God. It enables our bodies to be transformed in the resurrection. So there's a real idea of transformation. And that was the issue, I think. If Jesus were just a creature, how could he communicate the life of God to us? and yet they assume that that's what salvation is, giving us immortality and a new relationship to the Father. Okay. Well, the key figure, I hadn't gotten to mention yet, in the opposition to Erie become the St.

[13:02]

Athanasian. who became a Bishop of Alexandria in 328 and was kind of junior cleric at the time of the Council of Nicaea. But Athanasius develops a whole theology and many works arguing that Christ must be as much God as the God of Israel, part of the same being, part of the same substance, if he is to do for us what God does, what means saving us. whereas the Aryans wanted to keep a sort of stepwise graduated picture of Father and Son and then ultimately Holy Spirit sent by Judah. Okay, and the council in this big hubbub in 325 eventually Constantine said we've got to get everybody together and come down on a unified division and so a council gathers in Nicaea near Constantinople in Asia Minor and it's the first sort of universal council of the church that we talk about and at Nicaea the bishops apparently

[14:06]

debated the issues, were prodded by the emperor to come up with a single solution, and ultimately produce what we call the Nicene Creed, an early version of the Sunday Creed, which is really from Condon and Opal, 381. But the Nicene Creed, the Creed of Nicaea, is an earlier version that has a little bit more about the person of Christ in it. And the key issues there was a version of a baptismal creed that had been used in Antiochusy. But the bishops there agreed to add to it some phrases. And so they say that, I can read you the key passages of the Creed of Isaiah. Well, it's in there someplace.

[15:20]

Anyway, it says that we believe that the Son is begotten before all ages from the Father. Now, everybody could agree on that. He's the first produced. But it's as God from God, light from light, true God from true God. That's tough stuff. God from God. and light from light seems to be a way of how do we imagine this generation not like the generation of an animal or human being where you have first the parent and then the child which shares DNA with the parent but like light coming out of a candle or a lamp and then true God from true God so we're not just using the word loosely a begotten but not made A big distinction that's going to play a big role in the fourth century. Begetting isn't the same as creating. At the age of 65, you create a cake or a shit. We make things.

[16:21]

But begetting is different. There's a continuity of substance between parent and child. Of one substance with the father, homoousios, as it says in Greek, the same thing as the father. And it added, which was dropped in the later creed, from the substance, that is, from the Father's substance. Now that, it seems to us, kind of remote. What do they really mean by being from the father substance or one substance with the father? And it was not that clear in the fourth century. But a lot of people took this, a lot of bishops in the Eastern Church, took this as very strong language, saying that Jesus is the same thing as the father, the same thing as the God of Israel who spoke to Moses, or whatever that is. And to a lot of people, that sounded dangerously exaggerated. It sounded like they were saying there's really, at the base, no difference between Father and Son. And if you say that, you seem to be saying that Jesus' language, teaching us the Lord's Prayer, dying on the cross, are all in some way an act.

[17:33]

that he isn't really different from the father, he doesn't really obey the father because he's the same substance, the same thing. So a lot of people after the council were not happy with the formula that they had signed off on. The council makes a very strong statement as a way of rejecting area. But a battle goes on for the next 50 plus years, arguing about how to interpret this. And that's where Athanasius played a big role. The emperor, Constantine, died in 337, and he didn't really want to get too involved, except he wanted everybody to shake hands. He wanted them to recede areas back into communion and to kind of make up and say, okay, this is all behind us, let's get down to pastoral practice and keep the peace in the empire. When he dies, Constantine's sons then succeed and eventually knock each other off, except for one son, Constantius. And Constantius, his son, was a Christian and was committed to being a Christian, but he wanted to build unity

[18:38]

on the base of what seemed to be a more moderate division than the Council of Nicaea. The Council of Nicaea seemed to a lot of people to be fairly extreme, overly emphasizing the unity of father and son. And so, as I say, a lot of bishops wanted to back off and be somewhat more vague about the relationship of father and son, or to say, using biblical language, the son is like the father. He didn't like the Father in all things, but how they are one and how they are two, let's leave that to the mind of God. So there's kind of a desire to be a little bit vaguer on the part of a lot of Eastern bishops, like Cyril of Jerusalem, a great liturgical writer and teacher. He's a little bit vague on these things. And Athanasius, on the other hand, who was sent into exile five times, is kind of a stormy figure, and who does a lot of politics in his own way, is convinced that unless you stick with the formula of Nicaea, and really affirm a very strong unity between God, the Father, and Jesus,

[19:44]

salvation is ultimately inconceivable. Jesus has to be a divine being present in a human nature in this world. So it's there that the Cappadocians, who we're talking about today, kind of enter the scene. They're born just toward the end of the time of Nicaea and spend their lives really in a church that is becoming more dominant in the Roman Empire, culturally and politically, but where there is a lot of dispute about the role of the Council of Nicaea and the decision of Nicaea. In the years between 340 and 375, there were all kinds of councils and synods meeting in the east, sometimes every few years. You can trace them through and they're very interesting. They represent different political groupings and they each issue a creed or set of canons or a statement.

[20:47]

A lot of them thought they were also an ecumenical council. It's the decision of a church to recognize Nicaea and not others, that really has kind of been a commitment to a certain theological division in the end. But the position the emperor was espousing was to keep things, as I say, somewhat vague, to say that the son is like the father, and that's really all that we need. As Athanasius is saying, unless you adopt the wording and the creed in Nicaea, you are, for all practical purposes, endorsing Arianism. You can't have it one way or the other, because you either have God or creatures. You either have the uncreated being who is eternal, or you've got those beings brought into existence by God. And Christ has to be on one side or the other. Either God before all ages with the Father,

[21:48]

related to the Father uniquely, or a creature. And he will ultimately argue that the passages in the Bible where Jesus seems to be using creature language are speaking about his human nature, that he has taken on a creaturely nature, a created nature in the Incarnation. But that his eternal I, his eternal subject, eternal center, is that of God the Word, God who is equally eternal, the Son of the Father, related to the Father always. So, Athanasius represents this one position, which Hermenius was a bit extreme. And I think it's the great achievement of the Cappadocian fathers, among others, to have developed a way in which Christians can think about this Nicene theology, this way of affirming the divinity of Christ, that doesn't mix father and son together, and that also allows for a genuine incarnation, which is paradoxical and mysterious, but which is not contradictory.

[22:56]

And I think it's fair enough to say that the Cappadocians, the three Cappadocian fathers we'll talk about, kind of invented our understanding of the Trinity. The language and the concept, the way of relating Father and Son and Spirit have become classical in the Church in the East and the West. And that's why they're so important. But the Cappadocian Fathers we usually refer to three people at least, Basil of Caesarea, his younger brother, Gregory of Nyssa, whom we'll talk about tomorrow, and then their mutual friend, Basil's college roommate, if you want, Gregory of Nazianz, who was not a relative, but was a close associate. There are other people, Basil and Gregory of Nyssa had several other siblings, an older sister, Macrina, who seems to have been very learned and played a big role in their lives, a younger brother, Peter of Sebasti, who was also a bishop and wrote some letters, and maybe some others.

[24:03]

There were other brothers and sisters. Gregory of Nazianzus has a cousin, Amphilochius of Iconium, who also was a theologian, and we have some of his work. So there's a whole group of people who worked together and corresponded with each other and pursued basically the same goals in developing a theology the church could live with. Today I want to talk mainly about Gregory of Nazianzus because, as I say, I think he is a central and very important figure who helps us understand what they're getting on about. He's known in the Greek tradition, the Orthodox tradition, as Gregory the Theologian. One of three people who has that title of John the author of the fourth gospel is John the Theologian. Gregory in the 4th century, and then in the 10th and 11th century, the poet and preacher Simeon the New Theologian, who's thought to be so good that he's kind of the new Gregory of Nazianzus, not so well known in the West.

[25:08]

But Gregory of Nazianzus is called the Theologian because he was thought to be the only person besides John who really helps the Church talk about God, helps the church conceive what God is like, and to put it into words. And he is a great wordsmith, a great rhetorician, somebody who can kind of put things in a way that becomes memorable and unforgettable. Gregory was born around 326 to 330. We're not sure of the exact date, but sometime in the late 320. His father was a Christian bishop and his mother, Nana, was a devout and very learned person. who seems to have been from a wealthy, well-connected family. Probably both parents, in fact, were people of mean and had been highly educated and belonged to the kind of cultural elite of their time, as did Basil and Gregory of Nyssa.

[26:11]

Gregory's father had been, it seemed, a member of a kind of a sect. We're not exactly sure what they held, but they seemed to have had strong Jewish features, kind of a Jewish Christian sect in Central Asia Minor. And when he married Gregory's mother, Nona, he became an Orthodox Christian and confessed the creed of Nicaea. Though he seemed to have had some confusion about what was teaching, Gregory told us. Eventually they had three children. He became bishop of a little town in central Asia Minor, the town of Nazianzus, which is very small. I think he probably only had one or two priests and a clergy. I visited there a few years ago. Cappadocia is kind of the middle of Turkey. Still a kind of remote region. And it's an amazing landscape. It's something like Utah, I think, or, you know, southern Colorado, if you can imagine it. I mean, it's a high, semi-desert area with high sandstone cliffs and rocks that are sort of sculpted by the wind.

[27:19]

And there are salt lakes there. A lot of it is very dry, but the cliffs and rocks have a lot of caves in them. some of them had been enlarged by human construction, and since probably the early church, monks and solitaries have lived in these caves. There's a lot of them now that had been painted with frescoes. There's a whole monastery in one of them connected by little tunnels and staircases. There's a beautiful refectory you can visit, a chapel that's all painted with frescoes. This is from the 10th or 11th century. But it's a place of a very striking natural beauty in a wild kind of way. In the time of the Cappadocian fathers, It was a part of the Roman Empire, but a Greek-speaking part of the Roman Empire, a province of the Roman Empire, kind of smack in the middle of present-day Turkey, on the main road from Constantinople across the center of Anatolia through what today is Ankara, Cappadocia, and then down to Antioch and Syria, the great cultural center.

[28:27]

So it was sort of important as being on the crossroad. The main city is Caesarea. where Basil and Gregory of Nyssa grew up. Nazianzus is kind of up in the mountains, remote, and yet very beautiful, and a place that had been Christian for a long time. Probably most of the people still spoke a Celtic language rather than Greek, except for the educated class. Gregory's father was the bishop there. Gregory Jr., the second child, the first boy, was given a good education. He seemed to have been trained locally and then sent with his younger brother, Caesareus, to Caesarea and Palestine, where Origen had worked and got into the Origenist style of thinking there, probably consulted the Hexapla in sixth column. Then he went on to Alexandria for a year, I think. studied there with Neoplaton, a philosopher, and then decided he wanted to go to Athens. Athens was sort of the Harvard of the ancient world.

[29:31]

Not a lot going on commercially by this time, but the center of philosophical and literary studies. And so he goes there and spends about eight years living in Athens, going to lectures, and taking part in the life of students and developing his own mind. After he was there a few months he was joined by another Cappadocian who was Basil from Caesarea. Whether they had known each other before is not certain but they shared a house apparently in Athens and he describes in his letters and his poem how they really became deep friends and centered their friendship on their Christian faith, read the scriptures together, prayed the psalms together, led a sort of purposeful Christian life, and then also took part in the debates and philosophical reflection of their day. Their contemporary there in Athens was a nephew of Constantine, Julian, who later became the emperor, of that more in a moment. But Basil and Gregory

[30:33]

lived together in Athens, and got involved both in cultural things and in religious studies there. And about 357, Basil goes back home to his native city, Caesarea, the capital of Cappadocia. His father is an important teacher of rhetoric there, and he's one of a large family. When he gets home, he's baptized about the age of 30, and takes this as the invitation to lead a more focused Christian life. As we know from the example of St. Augustine, from the Confession, it was customary in the late 4th century for Christian families not to baptize male children until they were married and settled down. Girls, you can baptize a teenager, but guys, you didn't. And the reason, apparently, was that it was assumed that you would sow your wild oats before you got married. And because the church was thought to be very strict in its moral expectation, a baptized person who commits serious sin has to become a penitent and spend years, if not the rest of their life, in public penance, although they can be received in communion.

[31:49]

And so to avoid that, it was thought that you would commit whatever sins you're going to commit before you get baptized, and then get baptized as an adult with a spouse and a family and an occupation, or even on your deathbed. Augustine and others realized that's a dangerous game, because you could die before you get baptized, and what happened then? So both the Cappadocians and Augustine urged people to be baptized earlier, and even as infants. But they were baptized themselves in there about the age of 30. So Basil goes back and is baptized, begins to devote his life more seriously to studying the Christian scriptures and reading Origen, the great commentator, preacher. Gregory returns probably a year later, 358, sometime like that, and goes back to his father's house in Nazianzus, but Basil and he are still in touch. Basil invites them up to their country estate up in northern Asia Minor in Pontus, where they have a large property.

[32:58]

His sister Macrina had a kind of monastic establishment there, not formally monastic, but she and the local peasants and the people who work for the farm would say the psalms every day and lead a very simple life of prayer. So Gregory and Basil together spent many months up there praying together, studying Origen, making excerpts of things from Origen on how to interpret the scripture. This is kind of the middle time of their lives. Gregory and Basil apparently both taught rhetoric, taught young men how to be good Greek speakers. In 361, Gregory's father, who's getting old and is a bishop, pressured him to be ordained a presbyter, to help him, to be his right-hand man and preacher in the church in Mattheander. And Gregory said that he really didn't want to do this, he didn't want to get tied up in affairs and politics of the church, but his father kind of forced him into it.

[34:01]

And as soon as he was ordained at Christmas 361, he reacted the way he's going to react a number of times afterward. He fled. He's a very complicated person. So he fled up to stay with Basil and his sister and brother in the northern part of Asia Minor. And spent most of that winter and spring up there, kind of letting this settle down. But by Easter of 362, he's back in Nazianz. and gave a couple of his earliest sermons explaining why he had fled and saying that the reason is his high sense of the priestly calling. He was terrified by this and needed time to sort of settle down and pray about it. But he remains there working with his father, helping in the church for a few years, and probably doing some teaching as well. In 370, Basil has by this time come back to Caesarea and decides to put his name in for bishop when the previous bishop died.

[35:04]

And so Basil, who's a much more political and enterprising person, manages to build up a backing, push for others to vote for him, including Gregory's father, and is elected bishop of Caesarea in 370. This is a major position. It's the senior bishop, the archbishop, we would say, the metropolitan bishop of the whole province. And Basil is committed to the Council of Nicaea, he knows his oaths, and he also is a follower of Athanasius. But the Emperor is not. The Emperor is still pushing for a somewhat more vague compromise. But the Emperor and Basil are on a collision course, and there are several letters where Basil tells off the Emperor and confronts him to his face. He's afraid of nobody, and a very forceful figure, and a great preacher. Basel, as you know, is also organizing now the beginnings of ascetical life in Asia Minor, a different kind of monastic or ascetical life from what you have in Egypt, but one that's to be very influential on Benedictine, on the Western tradition, a more urban kind of monasticism.

[36:11]

And his rule, or his really kind of little conference that he did, gets translated into Latin fairly early. But I think he was just thought of as one of the safe figures, you know, like Cashin, who of course is interpreting the Manassas desert tradition. But Basil's approach to monasticism is really a more urban kind. I mean, it seems that his conferences are written also for lay people, for anybody who wanted to follow the Christian life seriously, but he had organized groups of men and women. who would work and then sell their products to support themselves, and they also ran guest houses and hospitals for the indigent, the sick, and did kind of charitable work that the Egyptian monks were not doing, and even would wander around to various cities witnessing to their gospel in a simple sort of way.

[37:19]

So it's a very influential and different style of monasticism. Basil, then, is a powerful central figure and is very concerned to populate the little cities of Asia Minor, of Cappadocia especially, with bishops who were favorable to his cause and his vision of the church. And so he kind of twists the arm again of his brother, Gregory of Myssa, and his friend, Gregory of Nazianzus, to become bishops themselves. Gregory of Nyssa was married, it seems, and was persuaded to become a bishop of Nyssa, which is a small town to the west of Caesarea. And he persuaded Gregory of Nazianzus to be ordained a bishop also, and puts him in a tiny little hamlet up on a crossroads in the mountain, a place called Sassima. And we know from Gregory's own writings that he felt very ambivalent about this.

[38:20]

He really, what his desire was, was to spend his time pretty much in solitude, writing letters, writing Greek poetry, being a kind of a learned, cultured Greek who was devoted to Christ. And ecclesiastical politics was apparently not his taste. This was getting involved in the big battles of the 370s. But his attitude also seems to have been, if you're going to make me a bishop, at least put me in a place where I can be seen in public. He thought perhaps he might be an auxiliary bishop, an assisted bishop in Caesarea. Instead, he's given this little one-horse town, it's basically a post office and a bar up in the crossroads, and it's also furious about that, it complains about it all the time in his letters and his poems. So he's hard to plead. And it seemed that he never lived there. He probably never even visited there, or maybe had just passed through. But continued to live with his father, and to do some kind of helping in the church in Asianda.

[39:24]

And then when his parents die in 374 or 375, or 374 actually, he withdraws again. He goes away and stays with a monastery of women in southern Asia Minor down near Antioch in Cilicia. And apparently there begins a lot of his writing and studying. While he's there, he gets more involved in the discussions of the Church of Antioch, which is a major center in the Greek Church, and also was split. There was an Arian bishop there, there was a very strongly Nicene bishop there, who was favored by the West, and there was kind of the middle of the rotor named Miletus, who was a friend of Gregory and his friend, and then there were also other people. So the church there was divided into a number of factions, each with its own bishop and its own clergy. The main, largest group under Bishop Meletius seems to have persuaded him to accept position in Constantinople of being kind of unofficial chaplain or pastor for the followers of Nicaea.

[40:34]

Constantinople is the capital of the Eastern Empire, the emperor and therefore the official version of Christianity is non-Nicene at this point, kind of half-Aryan, budging issues, but not affirming the Council of Nicaea. But there's a small and yet fairly influential group who meet separately and who do affirm the Nicene theology, the Son being of the same substance with the Father. Gregory had thought a lot about the Trinity, about Father and Son and Holy Spirit, and was a Nicene, and so he's persuaded to go there and become kind of a chaplain of this group. And conveniently, his cousin, a woman named Theodosia is married to a senator and she has a large palazzo in Constantinople, so he settles there with her. They use her front room as their church. It's called the Church of the Resurrection, the Anastasia, and the Nicene community begins meeting there. Gregory begins giving lectures and sermons there and becomes kind of the focal point of a new renewal of life for Nicene Christianity in the capital.

[41:42]

He goes there probably in the fall of 379, and right around that time, just before that, the old emperor had been killed in battle, Emperor Bawen. And Theodosius is elected emperor, and he's a westerner, a Spaniard, a Latin speaker, who is also committed to Nicaea. So everything changes when the emperor changes. And Theodosius eventually enters the city late in 379, and begins immediately to change the pastors and to line people up with the Nicene consensus which is forming. He seems to have invited Gregory, unofficially, to be the bishop of Count Van Rompel until this should be settled by a senate of bishops. And so he's acting as the bishop of Count Van Rompel through 380 and 381. And at this time, he gives some of his most famous speeches, which he later edits, really theological treatises, which are very important.

[42:45]

I mean, he's a writer, most of whose theology comes down to us in speeches, and also in poetry, long poems, short ones, and also letters that he writes. Basil died in 379. He just died right before Gregory got started. And so they're left kind of carrying the flame after Basil's death. So he's a very fascinating figure, I think, and reading his life kind of opens us to all the things that were going on in the church. He was trained as a Greek writer and poet, student of the classics, and so he likes to write narrative poetry. And we have two very long poems about his own life, autobiographical poems, written in Homeric, or in tragic verse, in sort of the same meter as the tragedy, that tell us about his life. And in some ways they're like the Confessions of St.

[43:48]

Augustine, different in the way they're set up, but both of them are very interested in autobiography and feel that in telling us about their lives and talking to God and these things, it becomes a way of involving us in their growth of faith. So he's a fascinating figure to read. But just something about his theology, and we can go on a little bit more this afternoon, As I mentioned, the Cappadocian, including the two Gregories in Basel, really are the people who develop for the Church a way of talking and thinking about the Trinity, about God as being both three and one without any obliteration of either side. By this time, by the 360, the discussion about the Holy Spirit becomes central too. Before this, the Holy Spirit was just kind of on the margins. Oh yes, the Holy Spirit. But now, suddenly, The relationship of son to father being more or less worked out and being of the same substance as the father, people began to wonder, well, what do we do with the Holy Spirit?

[44:55]

Is he also homoousios? Is he the same substance as father and son? Is he a creature? Is the Holy Spirit a way of talking about what God does in us? grace, transformation. Is the Holy Spirit really yet another figure in the divine mystery? And doesn't that complicate things, if you? And the Cappadocians really are the ones who work out vocabulary for thinking of this. They're saying that Father and Son and Holy Spirit are a single divine mystery, which we can call a single substance, single thing, a single reality. beyond any created notion of substance, but a way of talking about what's real. And yet within that divine substance we can distinguish Father and Son and Spirit as not reducible to each other, as being different from each other permanently, eternally, and being different essentially in the way they relate to each other.

[45:57]

As Gregory of Nyssa will say, the Father simply is, the Son receives the being of God from the Father by being produced or generated eternally, and the Spirit is sort of breathed forth by the Father and by the Son in a different way as a third aspect of the divine mystery. And so we have three kind of concrete individuals, three hypostases, or what in the West we call person, personas, which are all constitutive elements in the one substance of God, one reality we call God. This doesn't explain things, but it gives at least a way of thinking, well, what's one and what's three? A single what and three different who's, if you want. And Gregory tries to expound this in ways that left a big impression on the Church, especially the Eastern Church.

[46:58]

and which win him, I think, the title of Gregory the Theologian. His most famous work on this, probably, is a series of five lectures, or five sermons, in the summer of 380, which are called, usually, the five theological orations, and they're really a connected set of lectures about the scriptures, about the language of Father and Son and Holy Spirit, and about what you need to do to be in a position to think about this, and argue about this. Gregory is a great believer that people shouldn't get involved in these complex debates until they're spiritually mature. Otherwise, it simply becomes a way of showing off. So the first theological oration, which is a wonderful thing, is about the way you prepare yourself to talk about the reality of God. Because this is not just any old thing, this is God. And we're saved by our understanding of God. and by relationship to God. So the people shouldn't do this until they're in control of their lives, until they are living some sort of ascetical regime, until they have an attitude of reverence.

[48:10]

Otherwise it just becomes a lot of headstands. He compares them, in fact, to professional wrestlers, which I gather in those days were as and much actors as they are today, that the Aryans at this point are doing all these showy arguments, not because they really care in the conclusion, but that they want to be applauded and they want to look smart. Maybe that's unfair, but that's what he seems to be arguing. But just, I can read you a few excerpts from some of his He has many different lectures and sermons where he talks about the Trinity. Because to him, this is almost the theme he keeps returning to. The most important thing for Christians to get is some sort of a healthy way of speaking about God. And this means the Trinity, Father, Son, and Spirit, because this is what our faith is about. And it's something that we have to talk about. He says in one of his orations, an early one, which is called On Theology and the Appointment of Bishops, he says, one can scarcely achieve this, one can scarcely talk about God, except by training oneself in the discipline of philosophy for a long time.

[49:30]

By philosophy, he means not the modern notion of philosophy, but living the philosophic life, living the ascetical life. on channeling one's needs and one's desires. And so breaking off the noble and luminous elements of the soul little by little from what is base and mingled with darkness. But before one has elevated this materiality as far as possible and sufficiently purified one's ears and one's intelligence I do not think it is safe either to accept a position of spiritual leadership in a church or to devote oneself to theology. Before you've kind of got your act together, you shouldn't become a pastor or a bishop or study and talk about theology, which is partly what a bishop does. You need to grow and to be more controlled. And then he goes on to talk about, well, how do you go about this? What's the position we aim at? And he says, our argument should not lump the three together, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, into one individual for fear of polytheism, and so leave us with mere names, as we suppose Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are the same, as if we were just as ready to define all of them as one as we are to think each of them as nothing.

[50:50]

Nor should our argument divide them into three substances, three different things, either substances foreign to each other and wholly dissimilar, as that doctrine called Aryan madness would have it, or substances without origin or order, which are, so to speak, gods in rivalry. Christianity doesn't present us with three parallel gods, like the old Greek religions, nor does it speak about them as the creator and two creatures. And so that leaves us kind of in the middle ground. What do we want to say about Father and Son and Holy Spirit? And I'll read you from another oration of his, Oration 25, which tries to put this in plainer language. When he's giving advice to a younger Christian philosopher, he says, teach that the Father is truly a Father. Much more truly so than is the case with any of us, for he is so in a unique way, in his own way, and not as occurs with bodily beings.

[51:54]

As unique father of a unique son, uniquely. That's very Gregory and Isaac. He loves to play them. As a unique father of a unique son, uniquely, in a unique way. And he is holy father of one who is holy son. With us this is unclear, and from the beginning. where he did not beget later on so there's no time when the father begins to be father teach that the son is truly a son for he is unique of a unique father in a unique way and uniquely for he is not a father he always remains son teach that the Holy Spirit is truly holy for no other spirit is like him nor holy in such a way his sanctification does not come by way of addition but is holiness in itself becoming neither more nor less, neither having a beginning nor coming to an end. For common to Father and Son and Holy Spirit is both the fact of not coming to be and divinity.

[52:56]

Common to Son and Holy Spirit is being from the Father. Particular to the Father is being unbegotten. Particular to the Son is being begotten and to the Spirit is being sent forth. And if you seek for the manner, what will you leave for them who are attested by Scripture as alone, knowing each other, and known by each other? I read a few verses. Or even for those of us who will later be illumined in the light to come. So we can't even hope to know the way in which the Son comes forth or the Spirit is sent. But we have to think they're a distinctive relationship. And that's really important to our faith. There are a number of other passages where he talks about this. The one without beginning and the beginning and the one who is with the beginning are one God. That's kind of avoiding the technical language. Being without beginning is not the nature of the one who is without beginning, nor is being unbegotten.

[54:01]

Nature is never a designation for what something is not, but for what something is. The Father is the one who is without beginning. The Son is the beginning of all creatures, and the Spirit is the one who is with the beginning, who brings things that are created to perfection. He goes on in that line using non-technical languages to formulate what he's reaching out for. But he says, in another oration still, number 23, they are one in distinction and divided in unity, if I may utter a paradox, not less to be honored because of their relationship to each other than each one is when understood and taken on its own. A perfect triad are three perfect members, with a monad stirred into motion by its own richness and a dyad surpassed and the triad defined by its perfection.

[55:03]

It sounds very rhetorical, almost as if he's playing on words, but this comes up in almost every one of his orations. And I think the reason is, for him, pastoral ministry and living the life of the church means taking a stand on this, it means somehow being related to Christ through the gift of the Spirit and walking with Christ to the Father, being kind of caught up in this inner give and take which he sees as the life of the Trinity. And so for him the key to a faithful church is that they have a notion of the Trinity. and that's what makes and breaks the life of the Christian community. A right notion of the Trinity. And I think this is a notion which in some ways I think we've lost grip on in the West, but in the East you'll notice this being emphasized all the time in the Orthodox tradition, that really the Trinitarian dimension of God, which is not simply holding all three together, but also is not dividing them, is kind of the central paradox or mystery that generates the life of the community and comes into the sacraments.

[56:17]

So, just something to think about. We'll talk maybe more this afternoon or this evening about Gregory and his vision of Christ and of ministry at priesthood and some of the other things and whatever you'd like to talk about, but I've got to a work of his that you might, if you have time, you might look at. This is one of his other orations. It's a Christmas oration, and it's one of the most famous orations, I think, in the history of Christianity. You may know this already. Part of it is read in the office. I think it's one of the most beautiful pieces of preaching that we have in the Christian tradition. But, and there's a little introduction there to give you some kind of background, but it seems to be given as part of the Christmas festival in 381, toward the end of his time at Constantinople. And he's talking here about the feast and about the liturgy of Christmas, but then he eventually, after a certain amount of clearing his throat, gets to the mystery itself around Chapter 13.

[57:22]

and tries to characterize what is this mixture of the divine and the human that we recognize in Christ. So, if you have the time to look at that, it would give you a sense of how Gregory writes and works. Would you like another? We'll order one more. This evening. This evening, right. At 7. At 7 o'clock. Great. Thank you. You can stop by my library. Oh sure, that'd be fine. I'd love to, that'd be great. She was the one who seemed to have lived up there more permanently with her mother, and then her mother died. But they lived up in the mountains, this kind of territory. And there are a number of things.

[58:23]

Gregory of Nyssa has a life of McCriner, which is a famous poet. And if you read that, it's a wonderful thing. And I, in architectural, was going to try to discuss the Holy Spirit, the old robin spirit. Yeah. We don't know. Right. All the way up in the ceiling. It's an open book. Spirit. He's aware. Things. I don't know. Instead of the Holy Spirit. They're paying the bills and people. I think it might have been related to the Celtic languages, the Irish and the English. So I don't know if they were Irish, but they

[59:33]

They spoke those Arab Greeks to Dickie. I think they had land. They had property, you know, to rent it out. They wanted workers, and they kind of cultured people and took pupils, but they were basically living off the state. By the way, thank you very much for graduating at the end. I was kind of lame for it, so. Oh, well, well. From glory to glory. Oh, that's wonderful. Yeah. I never read. He just looked foreign to me. You make it very interesting. Well, I think you're kidding. I don't know. Well, it looks like I missed a whole collection of stuff that I've been doing. This is here. This is stuff that Ralph was in.

[60:53]

We translated that.

[60:55]

@Transcribed_v004

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ