You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Journey Through Spiritual Dimensions

The talk explores the concept of life through the lens of religious, spiritual, and philosophical traditions. It discusses how life is defined and understood in various disciplines and emphasizes the spiritual significance and ambiguity of progress. The talk also explores spiritual growth stages modeled by Origen, highlighting the dynamic and non-linear nature of spiritual maturity. Life is linked to spiritual practice and transformation, drawing heavily from biblical texts, the teachings of St. Benedict, Origen, and others to illustrate the continuous quest for deeper understanding in the spiritual journey.

Referenced Works and Their Relevance:

-

The Bible, New Testament (Prologue of St. John): Illustrates the intertwined concepts of life and spiritual light through the figure of the Logos.

-

Encyclopedia Botanica: Used to highlight the complexity and difficulty of defining life.

-

Psalm 63 and Old Testament Scriptures: Discuss the philosophical and spiritual dimensions of life emphasizing divine love and spiritual fulfillment over worldly life.

-

Gospel of Mark (Chapter 16): Provides the teaching that spiritual gain surpasses earthly life.

-

Ecclesiastes: Analyzed for its skepticism about human efforts in progress and wisdom, offering a critical view of material pursuits versus spiritual fulfillment.

-

St. Bernard of Clairvaux - Letter to Abbot Warren of Alp: Discusses spiritual perfection and the continuous pursuit of spiritual growth.

-

Origen and William of St. Thierry’s Works: Present foundational frameworks for spiritual progression, examining stages of life in relation to spirituality.

-

Thomas Merton's 'Love and Living': Offers insights on life from a spiritual perspective, emphasizing love as the perfection of life.

-

Karl Rahner’s Theology: Highlights the transformational view of life in the spiritual context, focusing on future creation with God.

-

Clement of Alexandria: Presents early classification of Christians into contemplatives and simple believers, forming a basis for future spiritual classification systems.

-

Rahner’s notion of God as the God of the Future: Underlines the importance of living life in openness to God, integrating past experiences into a creative future.

-

St. Teresa of Avila - The Interior Mansions: Referenced for its teachings on spiritual graces and humility.

-

McCabe’s Articles on Knowledge of God: Emphasized interaction with others as a means to enhance life and spiritual progression.

-

Mozart’s Artistic Example: Discussed in terms of maintaining traditional forms while focusing on content, illustrating the balance of continuity and creativity within spiritual and artistic life.

These references collectively illustrate the multidimensional nature of life from a spiritual perspective and provide an analytical framework for studying personal and spiritual growth within religious contexts.

AI Suggested Title: Journey Through Spiritual Dimensions

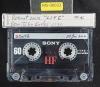

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

Speaker: Dom John Eudes, OCSO

Possible Title: Retreat 2002 LIFE #4

Additional text: 7:15 P.M.

@AI-Vision_v002

May the divine assistance remain with us always. Tonight we're going to talk about life. A major theme of the Bible that's present throughout the writings of scripture and all styles and times is life, in Greek, zoy. Hebrew and Aramaic call it chayim. In contrast with some of the other terms we've reflected on here, the word life is quite consciously studied these days and given a great deal of attention, but it's not proved easy to define. I looked it up in the Encyclopedia Botanica, and their approach is very interesting. They begin by saying that life is so complex that no one definition is satisfactory, so they're going to define and discuss life under seven different headings, and they proceed in that fashion.

[01:20]

Well, that's partly a result of the great interest in that question and also of the tremendous amount of research that has produced information that has not as yet been able to be all brought together so as to present a clear concept of just what life is at all levels. Of course, life is an analogous idea, scripture. The living God lives in a way that transcends any concept of living that we can form from our experience on earth. His life is so much more full of life, absolute, that we can't conceive it.

[02:27]

Repeatedly, we're appraised of new insights relative to this concept in various areas of research and reflection, from biology and embryology to medicine and law. What life is has become a very important legal question in our country. Our understanding of life is being enriched at the biological level with an abundance of fresh discoveries and theories that's difficult to master. It's interesting that since the discovery of the structure of DNA, it's been worked out that all forms of life, even moss, and trees and plants have the same basic structure and approach to reproduction that we do. But that wasn't known until after 1960.

[03:32]

DNA, the formula, was worked out in the 1950s. So that there's a whole new feeling about the way we relate to organic creation, to what lives, what is life. When you study chemistry, you begin with inorganic chemistry. It's the first course we took, and then quantitative analysis, and then only organic chemistry, and then biochemistry. So those are the levels, but from organic chemistry on you're dealing with life. To take a single example, the understanding of the structures and functioning of the cell, the basic unit of the human body and of life in general.

[04:37]

Animal and plant has itself become a specialty. It has become the frontier where a whole new science of life is being constructed. As data influence our understanding of ourselves and the various forms of life that are found in our world, and so our relation to them. These findings also have had a great influence on civil law in a variety of ways. Their implications for medical ethics and moral theology has been vast already and promises to grow even more with further developments. We're all aware of that now. Thus it would seem worthwhile to take up this word in its turn, give it our attention in the hope that by turning to it with a fresh attentiveness to its significance for us as Christians, and specifically as monks, we might be able to profit from a greater sensitivity to some of its spiritual significance.

[05:49]

After all, St. John in his prologue made a point of redefining life In a brief and stirring phrase, which he associates closely with the divine Logos, and life was light. Life then has to do not only with such things as farm, structure and function, but also with the mystery of human understanding. The light he's talking about is not material light, it's spiritual light. I have a little crucifix that comes from Crete in the 600s of which may It's got five letters on it.

[06:49]

And reading down, it's Zoe and Foss. You can write them in five letters because the omega is in the middle of both. Life, light. It was a Christ who is life and light on the cross. It's a very strong symbol. The original is in the Museum in Washington DC, the Freer Museum. So that's straight out of the Gospel of Saint John and it's in the prologue because it's thematic that he's going to present the life of the Logos made flesh as the light of the world. So there's a very close relation between light and life. Martin pointed out to me this morning that there's just one place in the Old Testament where it's stated that there's something better than life.

[08:01]

So I looked it up and found it in the original Hebrew scripture. Your love is better than life, or your chesed, your firm love, or your merciful love, is better than life. We sing that in Psalm 63, verse 4. Life is movement. at least movement of chemicals. You can have life that doesn't move in space, but it's not to be alive within the cell, there has to be an exchange with the outside world.

[09:03]

Whether change is to be evaluated as progress or decline, Whether a quality that heightens life or a defect that tends to its dissolution will vary with the norms used for the appraisal. Jesus himself was decidedly interested in the question, though of course he worded it differently. We often hear the passage, for it occurs frequently in the liturgy, It's from the Gospel of Mark 16. The one who wants to save his life will lose it, but the one who loses his life for my sake will gain it. What advantage, in fact, will a man have to gain the whole world if the price he pays is his life? Or what will he give that has the value of his life? In this view of things, progress consists in learning how to lose everything held dear in this life, including life itself.

[10:12]

This presupposes a different norm than that customarily used in deciding if a man is progressing in his chosen field of endeavor. Actually, such a distinctive and different manner of conceiving the value of one's life is characteristic of the whole gospel. Once again it is Matthew who gives the most eloquent expression. His words tend to haunt one with their spiritual beauty. Blessed are the meek, for they shall possess the land. Blessed are they who mourn, for they shall be consoled. Blessed are they who hunger and thirst after justice, for they shall be filled. Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy. Blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God. Progress is the law of life. Though this principle is true in one respect, it needs to be qualified by a closer analysis of what is involved in the concrete instance to which it is applied.

[11:19]

This law can be accepted as valid, but only if one is very careful to establish the norms by which progress itself is to be judged. As has been pointed out, our current generation has made the disconcerting discovery that certain forms of progress are disastrous in their effect on the long-term good of our human society, and so on life. Our century has experienced tremendous assaults on the concept of progress as inevitable, beginning especially with the First World War. Progress in technology, among other things, meant that the Second World War resulted in even greater casualties and destruction than the first, terminating in the atom bomb. The same kind of ambiguity attaches to all technological advances and improvements. The astonishing inventions in the area of communications in the last 50 years has resulted in many improved services to the sick, for example.

[12:26]

This occurred recently in Rochester, when the local physicians were confronted with a rare and dangerous disease. They handled it by communicating with specialists in Germany, who had success in treating such cases. They knew that from the literature, so they could go back and forth on the internet. They did that quite successfully. The experience shows that these same media at the same time have facilitated the dissemination of corrupting images and views of life, which contributes substantially to the weakening and destruction of countless families. True wisdom has always been aware of the limits of material progress in all its forms. Already in the book of Ecclesiastes, such awareness is so keen that it can be said to be the theme of his work, as its opening words indicate.

[13:35]

Vanity of vanities, says Kohelet. Vanity of vanities, all is vanity. What do people gain from the toil of which they labor under the sun? What has been? is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done. There's nothing new under the sun. Is there anything of which it is said, see, this is new? It has already been in the ages before us. This is not representative of the tradition, however, being the extreme expression of this insight into the limits of progress due to human effort and amounting to a radical skepticism concerning the very search for betterment, a skepticism that approaches cynicism as she sighs sadly in profound disillusionment upon reviewing his own life and his professional activity as a student and teacher of wisdom. He puts it this way, I applied my mind to know wisdom and to know madness and folly.

[14:40]

I perceive that this also is but a chasing after wind, for in much wisdom is much vexation, and those who increase knowledge increase sorrow." For all his pessimistic conclusions, Gohelis continued to seek and teach wisdom all his life. He was good at it. We're told at the end of his book, he applied himself to the art of writing writing out his observations and reflections with clarity, wit, and a pleasing style, a fact which has not made it easier to decide the sum of his message. What is certain is that he gives us a great deal to think about and forces us not to overlook the limits of life, of the human condition, even at its best expression. Gregory, and this is, I pointed out yesterday, Also, in his commentary on Kohelet, makes the very same point.

[15:50]

He was impressed by that too in his first homily. More typical, though, of the Old Testament wisdom are these verses from a psalm that Saint Benedict cites. Come, children, listen to me. I shall teach you the fear of the Lord. Who is the man who desires life? loves to see happy days. Keep your tongue from evil and your lips from speaking deceit. Turn from evil and do good. Seek and pursue it. And so Saint Benedict says before the novice who is entering the monastic life, the enhancement of life. While many such texts seem to overlook the limits of human striving and to readily accept the happiness that we, in light of the New Testament, realize is unacceptably limited and oversimplified, yet others saw more deeply into the problem and explored the far frontiers of human anguish in the process.

[16:58]

Not only the book of Job, but also the author of Psalm 72 expressed himself to that effect. See, these men are sinners, he writes, and yet they abound in this world's good, having laid up riches. And I thought, so it has been in vain that I have justified my heart and washed my hands among the innocent, that I was liced a day long and chastised in the morning. But then I entered God's sanctuary and understood what end was in store for them. Clearly then, the concept of progress and of its ambiguity and limits was already well embedded in the Hebrew mentality and the Hebrew worldview from early times, and insight into these realities was considered basic to the good and happy and devout life. You have more chances of a truly happy life if you see clearly its limits.

[18:06]

and see that early. The holy man is also a person wise in his appreciation of how to pursue true wisdom as a process of growth throughout life, but is also sensitive to the pitfalls and many obstacles to success, which even at its best is limited by the decay of age and other threats to life. I just got an email just shortly before I came here from a very close friend of mine who is the head of a convent, and they have a school, a convent, and a young high school girl was just killed in an auto accident. She had to go home. to the girl's home and console the parents as best she could.

[19:09]

She was asking prayers for that, but that kind of thing is going on regularly. You probably get similar requests for prayers every week, if not every day. Not to mention what we heard in the refectory this evening at supper, that terrible thing in Africa where You know, kidnapping children and then making the best deal. In the period following the New Testament, as time went on and the Church gained experience of living out the Gospel in the world, waiting for the Lord whose coming was deferred, more reflection was devoted to the question of spiritual life and growth. Origen proved to be quite imaginative in devising descriptions of various stages in the spiritual life.

[20:09]

He was not the first to classify Christian experience. His predecessor at the Alexandrian school, the catechetical school, Clement of Alexandria, had already divided believers into two groups. The Gnostics, as he called them, the contemplatives would say today, were those whom we would also refer to as mystics, possessed a more elevated spiritual knowledge. He thought of them as more perfect, which means that they were more alive. The others were simple believers who could be saved, but who lived on a lower plane of spiritual consciousness. Origin System, on the other hand, proved more useful and became the basis for subsequent classifications. He considered there were essentially two major stages in the spiritual life, following in the steps of Plato, the active and the contemplative.

[21:18]

Though described quite distinctly, yet they are rather complementary than sequential phases of life, so that both kinds of operation are present at each stage. The contemplative life, on the other hand, is subdivided into physical or natural contemplation, and what he called an optica, that has the divinity itself as its object. He also calls this theology. Another division Arjun utilizes is mystical, physical, and ethical. Interestingly, he associates three books of the Bible with these three stages, the Canticle with the Mystical, Ecclesiastes with the Physical, and Proverbs with the Ethical. The characterization of these biblical works was to have a long-lasting history. Saint Bernard, an example in the 12th century, does the same thing.

[22:21]

He associates those three books with the three stages of life, which can be viewed also as not only stages of the spiritual life, but of life itself, of being more fully alive, the closer we are to union with God. But it's the fundamental divisions into three effective stages of growth that was to exert a vast influence upon the subsequent ages. After Origen, nearly all those who wrote on the spiritual life, considered as a lifelong project, adopted his threefold schema, even while modifying it in some cases quite appreciably. He determined the fundamental division, though, into three stages, although in one of his works he talks about 42 stages.

[23:24]

In his commentary on the Book of Numbers, he sees each of the 42 stages of the Israelites in the desert as symbolic of stages or aspects, you might say, of the spiritual life. All too readily, it seems, the impression is given that these represent distinct temporal divisions of the spiritual life and need some schema to state as much by their choice of categories, for example, beginners, proficient, and the perfect. Rightly to interpret origin, however, and in varying degree other spiritual writers, it's fundamental to recognize that these stages represent not so much temporal divisions as they describe three spiritual and mystical processes of transformation of the human person in the totality of his human being three differentiated dimensions that are only partially successive and that's an important aspect of life from my dealings with people in my own personal experience to be aware that

[24:42]

that we're always living on several planes at the same time. And to be conscious of that is very important. It can seem to people, and they can be discouraged by it, that they're falling back when they are attacked by some of the same problems they had when they were much younger. in the monastic life or in marriage. And in fact what's happened is that they're just dealing with a dimension of their life that has always been there but which has been submerged as other levels come into action and become increasingly important for them. So that what can strike them at first and is misinterpreted as a sign of regression, can in fact be a sign of progress.

[25:48]

If you progress to a certain extent on a more spiritual level, a level of greater understanding, greater confidence, you have less need to suppress conflicts that are threatening to you. And so as you repress them less, you become more aware of them and can be tempted by them, against faith and so on. But as the lives of many saints show, that can be the final purification or other stages in purification. You see that in the life of the little flower, for example, where her strongest temptations were the last three years of her life. also in St. Alphonsus Liguori. So significantly, in the article treating of this question of progress in the spiritual life in the Dictionnaire de Spiritualité, the two authors studied as demonstrating the most creative approaches to this complex questioner, Origen and William of St.

[27:03]

Thierry. And William is given by a far more detailed, lengthy study. I think the reason is that he's more concrete and more elaborate in going into it, especially in his Golden Epistle, which is analyzed in extensive detail. And some helpful observations are made concerning its insights and usefulness. William is very conscious of the issue of progress, to be sure. It seems very likely he had discussed it with his friend St. Bernard, who himself wrote on it at greater length than does William, and more eloquently. In a letter he wrote to Abbot Warren of Alp, 1136, shortly after he visited the community of that monastery, Bernard takes up this theme at the very beginning of this letter, which is full of charm and depth of human and divine experiences. He addresses the aged Abbott, who he says reminds him of the text from Ecclesiasticus, when a man will have been made perfect, then he begins.

[28:13]

Something like Abbott Pambo, remember I quoted him the other day on the first talk, because as he was dying, he said that I go to meet God as if I begin my spiritual life, my monastic life today. And that's what this sabbath did. For though he's due to receive the rest and crown of his years, yet he has the attitudes of a novice ready for the struggle involved in reforming his community's observance, this monasteria. ended by coming into this astution order. Why should he fear anything who, while seeing his physical house destroyed by age, is building one for eternity, Bernadasse? But is there not reason to fear that he might die before he has completed the spiritual edifice? These matters then naturally raise the question of the nature of perfection for a mortal person subject to a premature death.

[29:21]

Brenner's answer is both profound and ingenious. It's also persuasive, I believe. He writes, therefore the tireless eagerness for advancing and the constant striving for perfection is considered to be itself perfection. But if to devote oneself seriously to perfection is perfection, it's also true that not to desire to advance is to fall back. This whole letter pays reading and rereading. It's justly quoted precisely because of the words just cited, but the skill of the composition can be appreciated only in its full context. In any case, it's clear that William himself gave considerable thought to this subject of advancing in life, and had incorporated his conclusions in this treatise, which was written to Carthusian novices, that is to say, for men in a formation program for whom the question of progress was a keen one.

[30:29]

In the course of his lengthy introduction to the body of this document, William touches explicitly on this topic. Very interesting context, I think. If you are converted Israel, be converted, is a quote from Jeremiah. That is to say, attain to the summit of perfect conversion, for no one is allowed to remain long in the same condition. The servant of God must always either make progress or go back. Either he struggles upwards, or he is driven down into the depths. But from all of you, perfection is demanded, although not the same kind from each. If you are beginning, begin perfectly. If you are already making progress, be perfect also in doing that. If you have already achieved some measure of perfection, measure yourself by yourself. William makes a very interesting comment on this passage by way of citing some lines from Philippians.

[31:36]

Forgetting those things that are behind, I stretch out to those things which lie ahead, that all of us who are perfect think in this same way. His conclusion here is that perfection in this life consists not in arriving at some predetermined state of purity, but rather in moving ahead with ardor to what lies in front of us. One of the important insights that Rahner had is that God is the God of the future, and He's also the God of the past and the present, but that with God we are creating a future is an important perspective to maintain throughout life. William is akin to the Spirit, not only to Bernard, but to St.

[32:40]

Gregory of Nyssa, who taught this doctrine in the 4th century and elaborated it at some length, giving it great significance in his concept of the spiritual life as continual progress. Thus we see that William not only treated the question of progress in life, but by his dynamic manner of conceiving of perfection, gave it a central position in his conception of spirituality. I think one of the important insights relative to the fact that as you progress in the spiritual life, you live more life, that you are more alive. For people who later in life are converted to God, I don't know how many tell me how they feel they've wasted their earlier years.

[33:45]

I'm sure that many of you have heard this, but the fact is that nothing is lost. if we take our whole life and turn it over to God, because it all is soon taken up into the experience of God, into his mercy, and it is transformed there into a new form of life. It's not lost or forgotten, but it's transformed. That's a characteristic of our human life, that somehow we can put the whole of our past into a present decision and choice and surrender of self, so that life is open-ended, it's open to a future that is in God.

[34:48]

William repeatedly goes back to earlier stages, which had seemed to be put behind as he advances in this document, this golden epistle, to treat of the higher phases of development. In other words, the style in which he writes, which seems untidy. It's not the modern style. He'll go back to a stage he already talked about much earlier, and that's the way life works. I think that's probably why he did it. He was following the movement of life. This is the case even in the very last chapter of this treatise, when you expect him to be talking about the highest stages of the mystical life, since he had done that already to some extent. As we would expect, the subject of this section is the spiritual man. Earlier we talked about the animal man.

[35:57]

And there he discusses the most elevated of themes, the very nature of God himself and a man's vision of God. But then he describes the reaction of the one who has some glimpse of this pure being. This makes him aware of his own lack of purity and causes him to groan and weep over himself as any beginner. recently converted is led to do. In his final paragraph, William reminds his readers of the more basic attitudes inculcated from the very threshold of the monastery, the need for humility of being subject to everyone, of self-abasement, and living the hidden life of faith. basics goes back to at the very summit of the spiritual life. And it's interesting to me that St. Teresa of Avila does the same thing in her book on the interior mansions.

[36:59]

At the end, she addresses herself to those who may not have experienced the kinds of mystical graces that she describes in that work. But she points out there that humility can substitute for that kind of experience. Rahner then, later in this past century, develops that theme very extensively and convincingly, I think. William has firmly held conviction that life is too complex to be contained in a rigid and simple threefold scheme of growth from one stage to another. Rather, throughout our lives we must remain in touch with basics learned in the novitiate. Hopefully, obedience following the prescriptions of the rule Practicing self-denial and fasting and accepting correction, these are never put behind us, at least not for long.

[38:05]

On the contrary, progress entails a greater capacity for such practices, greater willingness and freedom in our exercise as we advance. To grow in perfection is to become more willing to accept and acknowledge one's sins and limitations and to assume responsibility for their consequences. The truly advanced monk is one who can be readily approached, easily corrected, and readily yields the better jobs and material things to others, whether tools, food, or clothing. To be perfect is to know oneself as insignificant. and to be willing to accept the consequences. Perfection at its deepest level, then, is renunciation of honors and success in the eyes of others. Progress in the spirit, to be sure, is paradoxical. It means entering true life by accepting to pass through death to all that is not God and those who are united with God.

[39:14]

William's view of life in the spirit as a superior existence, as the true life experienced already in this world, is summed up and echoed by Thomas Merton in one of the most insightful, I think, and one of the most eloquent passages in all of his writings. These lines which define life in terms of love give us a fresh view on the true nature and meaning of life and refurbish this word life with the radiance that reflects the beauty of the new creation. He writes, love then has a transforming power of almost mystical intensity which endows the lovers with qualities and capacities they never dreamed they could possess. Where do these qualities come from? from the enhancement of life itself, deepened, intensified, elevated, strengthened and spiritualized by love.

[40:31]

Love is not only a special way of being alive, love is the perfection of life. He who loves is more alive and more real than he was when he did not love. We will not know life in its fullness until we see God. Señor Inez has said that the life of man is the vision of God. It's like a Peter Botanica doesn't include that. It's one of the seven aspects of life. So Irenaeus says, the life of man is the vision of God. And he added, man fully alive is the glory of God. May we all experience already something of that vision so that we might even now witness to the glory that is our hope and our life.

[41:43]

Amen. That is from Love and Living in that book. And in there, that's a collection of essays and the one entitled Love and Need is love a package or a message. It's a very witty essay, I think it's on page 35. No, it's a series of essays. Love and Living. Yeah, all that he himself wrote, and it has a number of quite interesting things in it. I think another very significant writing of Merton, some of his best writing is in his collection of prefaces to translations of his work.

[42:52]

Yeah, those two books are quite striking, I think, in their statement of really deep insights into human relations and our relationships with God. But I personally think that's one of his most beautiful passages. The thing about Al Pacwa, I don't know that much about him, but I just remember the extreme blindness he had for years. This is what? Is faith coming to a life that was overshadowed by ambition and good sense or zeal or work or what? I was thinking of a different temptation. St. Alphonsus had his worst sexual temptations when he was 90.

[43:55]

Something to look forward to. It is, yes. He lived in great distress that way, and I don't think that's all that rare for the reason I gave, that I think when you're younger, you don't have to repress your sexuality very much. And when you get more confident, more involved with God, you have less fear of it, and a lot of it comes back. Also, I think another feature of it is the fact that sexuality becomes more personal and less biologically oriented, that's merely physically oriented. And so in some way, as you become more personal, it expresses more. And so it has more meaning.

[44:58]

Although I don't know enough about his detailed experience, whether that's been recorded, but that he was in great distress over that when he was 91, I think, actually. It's a fact, but the other type of trauma about faith, the little flower had so bad that she was afraid she might commit suicide. She told the infirmary not to keep any sharp instruments in her room, for example. She feared that she might, in a moment of distress, do something. I believe that that's a result of a kind of progress in the spirit in which God becomes so important that nothing else seems substantial and so as a result

[46:06]

You want more assurance than you can get from your senses, from your imagination, even from reason, because you can't prove anything. Her trial was feeling that the whole concept of God and of heaven was an illusion. And so she dealt with that simply by trusting more, surrendering. But it was a source of immense suffering to her because when she would think of heaven, instead of finding consolation, she would sort of feel that it's a mockery. And I think that's what it's from myself. Those kinds of temptations, John the Cross had it also. Speaks of the dark night of the spirit. And I think that's what is associated with the fact that they no longer have much invested in human emotion and so on.

[47:17]

It just doesn't have the same significance. And so there's no felt experience of reality that knowing God doesn't overflow. It transcends too much. One of the important things that I think is helpful in thinking about life is that we can give life to others by the quality of our relation with them, by putting our life in our words and our relations with others, we can enhance their life.

[48:19]

And in fact, in some way, life can't be enhanced except in relation to other people. McCabe says that type of thing in an article that I read today. The English Dominican wrote, I think, a rather powerful article on the knowledge of God. And one of the points he makes there is that we can give self to others. by affirming their self, and parents do that for children. We can do it for one another in varying degrees, but by seeing who another is and recognizing that person in a way perhaps that no one ever has, and affirming that person by our attitude, by the respect,

[49:32]

and affection that we show, we can give life and a sense of fuller being, of being more alive. What makes us more alive? It's a good question to come back to frequently. And I think that I was talking about this growth in the spirit It's not the one who's the healthiest, it's the one who has the greatest responsiveness, I think, to the presence of God in our being, who is most alive. But to think that we can communicate some of that to others, or God can through us, is I think a very most sobering and encouraging insight.

[50:42]

But once I was asking my kid, do you miss life in the monastery? Sure, you can't play pool or baseball. I know, yeah. No TV. I said, well, for me life is growth and there's a lot of room for it in the monastery. It's a good question, you know, what is your life? St. Augustine would say your life is your love. Bondus tuus, your weight is your love. Bondus tuus, amor tuus. Your weight is measured by your love. Look, as you said earlier, It's more difficult for the male of the species.

[52:11]

It is. It's actually one of our own. Yes. Well, I feel we can behave our true self. Definitely. We tend to work in... We tend to live in external... That's right. ...judge ourselves by... Well, I think redefining for ourselves just what love is and how we really experience it and see it is an important thing to go back to from time to time and to recognize in practice how we express our love where it is, that it is. And gradually, I think we can get more comfortable about learning to express that.

[53:21]

Some people in every community, I think, have to be able to express that. That was one of my discoveries when I worked for the Ardor as a whole. Some years back I was charged with working with all the houses of the Ardor throughout the world. One of the things that struck me is that in a community where there was no one who really had assimilated the tradition, by study and reflection and meditation and so on. In those communities, there was a tendency to think there's just one way of doing things, because that's all they knew. And that any change in that was an infidelity. And that restricts the possibilities of life.

[54:23]

Because life, as I mentioned there, life is change. There's also continuity in life, and that's what the tradition is. The tradition is the realities as they assume form in each generation. and have to be passed on. But somebody in the community has to be able to talk about the important elements in our traditions, or they can get lost. They seem not to exist if they're never talked about, or they don't take on a human enough form to be assimilated. But we all do that imperfectly, of course, but And the most creative people, I think, in the Western world have been those who have assimilated most the tradition.

[55:28]

Mozart's a good example. Mozart didn't create any new musical forms. He respected the ones he inherited. But that left him free to focus on the content. And so, in some way, he was certainly The artist who created most easily, when Beethoven began changing the contents and the forms, Mozart didn't need to do that. He also didn't need to hear his music as he wrote it. He could walk up and down and compose in his head. His wife says, and then he would sit down and talk to her while he's writing out what he composed. What did you do in the market today? And so on. He's writing out the 38th Symphony or something.

[56:29]

But learning to speak about it, I think, requires that we ourselves try to repeatedly live close to the point where we experience God, life, love, and meaning, you know, the basic ideas that sound so general and abstract, but which we're living every day. They form some of the same function, I think, that the koan does in the Zen people, because there's no one answer to these kinds of themes. But there are any number of answers that are legitimate and that approach them and help us to gradually be formed by them.

[57:41]

Oh, so there we are. Right. So tomorrow is a quarter of eight that we meet here.

[57:53]

@Transcribed_v004

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ