You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Eternal Echoes of Zen Practice

The talk explores the lineage of Zen practice and the intricate, often ineffable nature of teachings passed down from one teacher to another. It emphasizes living each moment fully without conceptualizing time and the challenges of grasping enlightenment in practical terms. The idea of practice is closely examined, focusing on how mindfulness and understanding are intertwined with actions in everyday life. Key discussions include the importance of Zazen and Doksan, the role of the Bodhisattva vow, and concepts like emptiness and non-duality. The speaker reflects on the Surangama Sutra and a narrative illustrating the continuity of effort and awareness, and offers insights into ethical living amid worldly affairs like war.

Referenced Works:

- Surangama Sutra

-

The sutra is cited as a source of guidance, specifically referencing a story about leveling one's mind, which metaphorically equates to maintaining an unbiased perspective and non-discriminatory awareness.

-

The Teachings of Dogen

-

Dogen's association with the foundational practices of Zazen and Doksan are highlighted, as well as his philosophical insights into the nature of time and practice.

-

The Concept of the Bodhisattva Vow

-

Discussed as a commitment to not attaining personal enlightenment until all beings are enlightened, integrating selfless service and interconnectedness as central to Zen practice.

-

"Skillful Means" and the Ten Bhumis in Mahayana Buddhism

- These teachings are introduced to illustrate stages of bodhisattva development that emphasize the progressive and infinite nature of Zen practice.

Central Figures:

- Bodhidharma

-

Mentioned in the context of early lineage and as a figure embodying Chinese interpretations of Buddhist ideals.

-

Suzuki Roshi

- Referenced throughout as an influential teacher whose teachings and presence continue to guide practice despite his physical absence.

AI Suggested Title: Eternal Echoes of Zen Practice

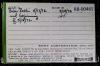

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

Speaker: Baker Roshi

Additional text: beginning of 5/18/72

Speaker: Baker Roshi

Additional text: cont.

@AI-Vision_v003

Our lineage, your lineage and my lineage, can you hear me in the back? Go back pretty far in history, maybe all the way to Buddha and before that even. But actually we know historically our lineage pretty accurately back to the 8th century or 700 something or other. By the time you get to the 6th patriarch, we don't know exactly. Before the 6th patriarch and particularly by the time of Bodhidharma, rather unclear exactly. Maybe Bodhidharma wasn't real. He's a perfect Buddhist from a Chinese point of view, who wants India to be a certain way. But from about the time of the Sixth Patriarch onward, there are fairly accurate historical records

[01:30]

of each teacher, all the way up through Dogon, through Tozan Ryokai, and then through Dogon's teacher, and Nyojo, and then Dogon, and then up through the Japanese lineage to Suzuki Roshi and to us. That's a lot farther than most of us can trace our blood parents. And even if you could, probably it's a much more real lineage for us than our actual blood lineage. But what that consists of, what this teaching consists of, that has been passed to us over and over again. Nobody knows exactly. Or, well, we know it, but we can't say what it is. There's almost no way to teach it.

[02:53]

There are so many tiny attitudes, ways of doing things that are what's actually past. There's no single insight or flash of wisdom that will convey to you this teaching. To think in that way is to have an idea of time. Now, at this time, such and such happens and I'll be enlightened. Each moment you have to be awakened, enlightened. There is no... Time, you know, the idea of time is just an idea. Actually, there's no time.

[04:32]

There's just events. Each moment you're an event. So you can't have time, or lose time, or waste time, or be on time, because you are time. Time itself, each moment. So our practice is each moment. And to practice our way, as I talked about last time I was here, about the story of the monk asking, why did Bodhidharma come from the West?

[05:50]

and the teacher saying, thank you for sitting long and growing tired, which is an expression meaning thank you for your practice or thank you for over and over again asking such a question. So questions are some help to us because, as I said, they're much bigger than answers. They don't have beginnings and ends. A question has some... A real question covers everything. You can't find an answer. So when we practice,

[06:58]

We start with as little as possible. There's no idea of time or space or self or anything. As much as possible, we start with no idea. But of course, you have ideas, so you need some antidote. But our practice is to have no idea, no nothing. not even nothing. So when we begin practice, we just sit with very little instruction. Dogen said that Buddhism is two things, zazen and doksan. But what is zazen?

[08:05]

When you do zazen, you're not any different than you were when you were sitting in a chair or eating. The only thing you're doing is you're doing as little as possible. But still, you can't say what zazen is. In doksan, it's the one relationship you have which you can't, although the way it's conducted is somewhat formal. Actually, there's no way you can say, oh, that's such and such, or that's my friend, or that's the person I go to the movies with, or that's somebody I'll do such and such. I have this kind of relationship. It's not clear what doksan is even. It's up to you to create what doksan or sansen is. In addition to doing zazen, we do take a kind of vow, and that vow, of course, is the bodhisattva vow to not achieve enlightenment until all beings achieve enlightenment, or maybe you could say to

[09:49]

recognize that enlightenment doesn't exist separate from everything. So what does that mean? You know, that's not clear what that means. And the vow, in another sense, is the vow that we take, the three refuges we take. Take refuge in Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Which is the important thing about that. One, you take refuge in Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. The other side, which isn't said, is there. You don't take refuge in anything else. So if we take refuge in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, what are Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha? I mean, it's nothing but... How can we take refuge when you're in trouble? What help is it when you're in trouble, some kind of crisis, to take refuge in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha? I don't think it's very reassuring.

[11:22]

But we take refuge in, actually, in nothing at all. But since you have some need to take refuge, some need to dream, the world is a dream, or we take refuge in Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. But the meaning of the vow is that if you find yourself taking refuge in something else, your practice is wandering off. It's not that what it's wandering off to may not be true. For instance, if you're interested in astrology, it may be that astrology is true, or a particular diet is better than another diet. And of course, you can eat any way you want if you have a bad stomach and you can't eat such and such, have a disease or no teeth, eat any way that's necessary. If you have a trip about it, a belief about it, if you're taking refuge in a diet, something that's going to help you, then that's not our practice.

[12:53]

We're not interested in ourself that way. The hardest thing to give up, probably, is the desire to be in conformity with the world. Whether you define that as IBM or the stars, it's still some desire to be in harmony with the world. Very difficult to give up. The other desire that's nearly impossible to give up, is the desire to have the world the way we want it to be. So it's very difficult to know how to practice. What practice is exactly? One student may say, well, I'm trying to be aware of everything I do, and when I eat chocolate, I think, ah, this is bad, I shouldn't eat chocolate. And then later, they, eating cherries, they think, well, cherries aren't so bad as chocolate, so it's all right, you know, to eat cherries.

[14:24]

But then they notice that the same kind of stuffing of their mouth is going on, whether it's cherries or chocolate or lettuce. So then they try to stop eating cherries and chocolate and lettuce. I don't know, maybe they have to eat lettuce sometimes. But this isn't what we mean by awareness at all, by mindfulness. It's just that maybe it's... if you eat too much chocolate, that's maybe stupid. But that's just practical. What we mean by mindfulness, you know, is when you're eating chocolate, you know you're eating chocolate. Not that you say it's bad. When you are taking a break from work and you feel you should work, Mindfulness isn't to get up and say, oh, I've noticed I'm taking a break, you know, when I should be working. It's just to notice now I'm taking a break. Acceptance doesn't just mean accepting what we don't like, too. It also means accepting what we like. So practice isn't so terrible that you have to go around accepting

[15:56]

you know, the Vietnam War or something terrible. Also, you can accept what you like, maybe eating chocolate. So if that's, you know, the case, how... just, you know, if you think about that at the first level, it doesn't make any sense because this world is pretty terrible shape, you know. If we just accept everything like that, without any idea of right or wrong, still we have this terrible problem of what's wrong. Vietnam War. Our own way we treat people. There's a thing I found, noticed the other day, in the Surangama Sutra, and it sounds a little bit like what we do here at Tassajara. It says,

[17:27]

Dharanimdhara Bodhisattva then rose from his seat, prostrated himself with his head at the feet of the Buddha and declared, I still remember that formerly when the Buddha of universal light appeared in the world, I was a bhikṣu who used to level all obstacles, build bridges and carry sand and earth to improve the main roads, ferries, rice fields and dangerous passes which were in bad condition or impassable to horses and carts. Then I continued to toil for a long time in which an uncountable number of Buddhas appeared in the world. If someone made a purchase at the supermarket, if someone made a purchase at the marketplace and required another to carry it home for him, I did it without charge. When Vishvābhū Buddha appeared in the world and famine was frequent, I became a carrier charging only one coin, no matter whether the distance was long or short. If an ox cart could not move in a bog, I used my supernatural power to push its wheels free. One day the king invited that Buddha to a feast. As the road was bad, I leveled it for him. The Tathagata Visvabhu placed his hand on my head and said, You should level your mind ground, then all things in the world will be on the same level.

[18:52]

Upon hearing this, my mind opened and I perceived that the molecules of my body did not differ from those of which the world is made. These molecules were such that they did not touch one another. So for those of us on a work trip, you can really get into that. I mean, you can, in the city, you can pick up every piece of broken glass you see. You can stand at the supermarket and carry people's groceries home endlessly. We can do, you know, whatever people ask us to do.

[19:54]

really being a servant. But that isn't what we mean by practice. Sometimes we do that. When you're trying to find out what it means, you know, say, to do whatever is asked of you, you maybe do that. When you try to be aware, maybe you're aware that now I'm eating chocolate and I shouldn't. How to practice so that those differences between carrying everybody's groceries home from the supermarket and doing your own work, whatever that is, writing poems or working as a carpenter or working to change something, like the war,

[21:45]

how you can practice so there aren't those dualisms is some mysterious thing, actually. Emptiness, we say emptiness or sunyata, doesn't mean nothing exactly or even everything exactly. Maybe it means that what you see with your eyes and hear with your ears and taste and touch

[22:49]

is not what you think you taste and touch and hear and see. But we have these desires to be in conformity with the world and to want the world to be a certain way, which are so powerful it's almost impossible to actually see. So we talk about a third eye in Buddhism. And many of these things you can understand, like many rock groups call them, talk about the here and now. But that's kind of a theological idea. Actually to live as if, not as if, but knowing you are time itself is quite different than kind of some theological idea.

[23:55]

to practice, and you can confront yourself with the idea, the awareness, even the intellectual understanding that you are time itself. Nothing exists separate from you. But it has no meaning unless you live as if that were true, live being that truth, which takes over, over, over again, bringing yourself back to that truth. So when we start sitting, we notice what we are, or what's here, something's here, some kind of activity seems to be here. But as much as possible, our practice doesn't have any idea about what's here. Some physical activity, maybe, some mental activity. So you can have a meditation, kind of meditation, based on what is seeing, what is hearing, what is feeling,

[25:21]

What is thinking? What is consciousness? When we use these words all the time, I see something, but do we actually know what we see, or what seeing is? We say, I'm conscious of something, but what do we mean by consciousness? Do you actually know your own mind, own consciousness. So we start with breathing. And in each breath, you know, there's a whole world. So there's no urgency in your breathing to be into the next breath. or doing something. Completely this breath. Completely the next breath. When you can breathe that way, your breathing changes in many subtle ways. There's no anxiety, just some deep relaxation. Then you can begin to notice what you hear, how you hear, if there's anything that you

[26:54]

Then when you're completely familiar with what hearing is, after maybe many years of noticing each moment what hearing is, what seeing is, then when we say, turn your ear inward, you know what that practice means, to turn your ear inward. So we sit without anything added, just what we find. We find we breathe. Then when we begin to take action in the world, it's an expression of our true mind. I think each of you can do it, actually. We're very lucky to have found ourselves somehow at the end, beginning, of this teaching. It's so old.

[28:25]

All you have to do is make an enormous effort, which is no effort, to make sense of the teaching and to give up making sense of the teaching. Does that make any sense? Suzuki Roshi says, when we give up seeing things the way we want to see them, when we understand that emptiness means that what we usually think we see is not there. All we see is holiness. So then what is holy about the Vietnam War? How do we deal with the problem of samsara and nirvana is same? Can you really solve that problem? We say samsara and nirvana are the same. Until you can solve that problem, you don't understand Buddhism.

[30:05]

First we have to end the war within ourselves. That doesn't mean we shouldn't take action in every way we can. To do anything that's actually effective take care of Tassajara, the kitchen, or some other person, or the situation in this country. Allah is the Greatest, Allah is the Greatest, Allah is the Greatest, Allah is the Greatest.

[31:43]

Last night I... Can you hear me in the back? You can also move up if you want. Last night I talked about how difficult it is to understand what we mean by practice. We say various things which It's pretty difficult to know exactly how to accept and to develop and practice and know, enter. Like, some people find that when they want to, when they try to be aware, mindful of their activity, it actually stops their activity. That's not what we mean. There's, as I said last night, we are a stream running from hundreds of years ago, 1,000, 1,000, 2,500 years ago and before. We even know the names of the people back to 8th century about, or earlier than that.

[34:31]

And each of those teachers, we could call this the way of the Buddhas and patriarchs, which means a way of practice, not just some teaching, but a way of practice. And each lineage has a rather, and each Mahayana lineage has nearly the same vows, but some slight difference. So, as the banks of a stream are, different streams are slightly different. And it's pretty difficult to know, to say exactly what those vows say, for Suzuki Roshi's lineage are. It's something that has been communicated by warm hand to warm hand, or person to person for many years, and each person spent usually 10 years or 20 years with their teacher, or longer.

[36:02]

So what we want to do is we want to enter the stream together of practice. How to get the hang of practice, get the feel for practice. Once you do that, then your practice begins. If you really have the feel of it, then everything becomes your teacher, and your teacher then can know, I-S-E, and he can make a prediction about you. But no prediction can be made until you enter the stream of our practice. So as I said, the three vows, the three refuges, take refuge in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha mean also not to take refuge in anything else. Maybe the three American refuges are juicing, doping, and sexing, is what most of people take refuge in. And there's nothing wrong with

[37:55]

inducing, doping, and sexing. But from our practice, it's not so good, because of many reasons. One is, of course, we violate the precepts, which are basically, the precepts are, do not change anything, do not add anything. But another difficulty is that it gives us a stronger sense of self, even though it may reveal something to us about our self, it still strengthens our self. Most of us have a... our secret desire is to finally have our special self acknowledged. We obtain the big E, enlightened. We think someday in the future someone's going to... He really is wonderful, he obtained the big E.

[39:29]

So if you practice with that idea, you know, you're actually just protecting that special sense of self that you don't want to give up. So how do you practice without the big E, without wanting some special acknowledgement? we say, accept everything as it is. And then, one side, we need that practice to accept everything in its literal sense, everything as it is. It's pretty difficult, and that's really difficult, to accept everything as it is. You know, if you're schizophrenic, you accept

[40:35]

I'm schizophrenic, completely, forever. But something may change, but still, if it keeps changing back into schizophrenia, well, okay. Or fear, or whatever it is. The Vietnam War, how do you accept it as it is? It's really a fantastic idea, actually, when you realize you can accept things as they are, not have to change them. Anyway, we need that openness to accept things. But it's so difficult to do, and, I mean, almost impossible to do if you live in the ordinary world, we have this kind of situation like Tassajara where it's not so dangerous and there aren't so many consequences to accept everything as it is. But the other side of to accept everything as it is means to work with everything, to be able to work with everything.

[41:58]

Why to accept everything as it is means to be able to work with everything is because to accept everything as it is means there's no you to interfere with anything. I've talked several times about the ten bhumis. And the tenth bhumi makes this very clear. The first... Anyway, the bhumis are very interesting. It's a funny word, I know. Anyway, I think the bhumis are wonderful. Anyway, they... At one end is... It's the same kind of idea as If you, as our vow to save all sentient beings, you know, it's impossible, we think, to save all sentient beings, but we should practice to save all sentient beings, not just to save ten or twenty. We should practice to save all sentient beings, or we should practice with all sentient beings, is maybe a better translation.

[43:30]

The same idea is that your practice, the infinite extension of your practice is Buddha, as the infinite extension of your practice is saving all sentient beings, or including all sentient beings. So the infinite extension of your practice is Buddha. So the tenth booming is when your You've done everything a bodhisattva can do, right? So each stage is a kind of stage of more all-inclusiveness. From the eighth stage, which is based on the steadfastness, which is based on vows, knowing when your birthday actually is, I think it's from the eighth stage. You don't just work through your own body. You work through everything. So we talk about dharma reflection, which means that there's no you left that teaches or acts or functions,

[45:03]

I don't know how to say. Anyway. So from the 10th Bhumi they say, at this stage the Bodhisattva can take all the world systems and reverse their order. Put the first one last, next to last one first, Then he can reduce them all, put them back in regular order, reduce them all to a mote of dust, all without changing the dust, changing the mountains or rivers or changing any person. Anyway, the meaning of this is that when you can accept

[46:11]

Everything as it is, actually. Meaning, not just that you accept everything outside you, the so-called outside you, as it is. It means inside. You can have skillful means. Skillful means, means you can work with everything. Because everything's changing. To accept everything as is doesn't mean it's some fixed pattern. because actually we're in participation with everything. Anyway, so first, to accept everything as it is means to... just what it sounds like, you know, accept it just as it is, good or bad. There's no thought, you know, there's no thinker behind the thought. Just whatever... whatever you...

[47:14]

I mean, you know, what Descartes said, I think therefore I am, something like that. Buddhism would say, thinking therefore thinking. The mix up there is he added, I think, so naturally he ends up with I am. But if you take away, all you actually have is thinking. So thinking, therefore thinking. So when you accept everything it is, it means thought, just thought. No thinker behind the thought. But how do you actually live that? Because actually we feel some fear or distress or we feel the world is some big problem, you know. So we fight with it, or we fight with our own feelings, rather than accepting them as us. So you have to recognize that any outer battle you have is an inner battle. The same thing you fight outside yourself is what you fight inside. And if you don't know that yet, then we say you live in a non-human realm.

[48:43]

consumed by your karma rather than able to work with your karma. For Buddhism, human means to be able to work with your karma. To be caught completely by your karma or consumed by your karma is like animal world or some non-human world. So if you only are fighting some battle out there, to stop pollution or end the war or leave your wife, you know, what. And don't recognize that as a battle within yourself for rejecting the same things in yourself. Then you are caught, you're caught really by your karma completely. Likewise, you can't recognize it as just in yourself, you know. We have to take some action in the world. We have so many ideas that interfere with our direct perception of the world. When we think, we have this strong idea that there's something thinking, but it's just an idea. And when we do a sasheen, we think there's one week

[51:02]

Now, for one week I'll sit." And Tsukiyoshi called this idea of time, he said in a lecture, don't do a sashin the way a horse does. And what that means in Japan is you don't do a... Your idea of time shouldn't be like the way a horse pisses. Because a horse just stands there and pisses a steady stream, you know? And it lasts for... then it stops. So if you have that idea of doing a sashim, you know? No, I'll do that sashim for one week. If you... your idea of time is like that. Anyway, Suzuki Roshi explained it that way, I don't know. But our idea of time is just that there's some event. We are some event this moment, and some event the next moment. And there's some, maybe some railroad tracks,

[52:35]

bring us to this point, our karma, but actually time is next breath, next breath. So you should be able to be relaxed and completely comfortable on each breath, as if it was and is the whole world, world systems even. no place to go or nothing to do, just this breath. It's so comfortable. There's no you there at all, just breathing. To actually sit still so that

[54:23]

your mind can be still, so that we can find out what our... Well, you know this, Buddhism says, some famous story about consciousness being like fire. So we think consciousness exists, but actually we don't, there's no wood fire apart from wood. The wood is burned up, there's no fire anymore. So to use up our wood, actually our conditions produce some activity. So to find out what you are, if you have no wood, you have to be able to sit quite still. Actually, I think the eighth Bhumi talks about the samadhi of cessation.

[55:35]

then thoughts and activities cease. But to have that kind of experience, which is certainly not necessary, but is a kind of shortcut, Buddhist shortcut maybe, you need to be able to sit still and straight. So at first, it's rather difficult. It's not actually so natural. Maybe another kind of naturalness. So you need to develop muscles which hold your back straight and which have some strength here. And then you have to explore. Notice what your breathing is. You have many kinds of breathing, depending on the conditions of your body and mind. many kinds of breathings, breathing you don't have access to because you don't have access to the kind of conditions which go with it.

[56:52]

Anyway, we start with our breathing as if it were the beginning of practice. And you let it settle deeper and deeper. So that eventually you can sit very still. The more we can sit still, the more we can be without would, the more you can see things as they are. First accepting things as they are, then seeing things as they are. And then when there's no you to interfere,

[58:14]

your actual participation with things as they are begins. So when we say everything is ordinary, or you just do things like everybody else, or you enter the forest of desires and passions, Seventh Booming. It doesn't mean what it sounds like to somebody who doesn't practice. Not exactly the same as just going out and trying to save the world. We talk about, we say, the secret body and mind.

[59:47]

and speech or words. It looks just like ordinary body-mind speech, but first you learn it with your teacher. The question is here, how do we actually hear each other? How do we actually speak to each other, know each other? You know, sometimes you meet some little kid and you can talk with him and you can know immediately he hears you. But some other little kid doesn't hear you. And he can go away and come back or you can say something to him and he'll do it or not do it or hear you. But what difference is there between you just meet some kid and he hears you, and someone else, some other little kid doesn't hear you? How can we hear each other? So when you have this kind of relationship with your teacher,

[61:16]

You're hearing him all the time, even after he's dead you can hear him. You begin to hear some kind of secret voice. You know exactly what he says, means. So if we practice together with the same vows, maybe we don't know what they are but actually we live them, we begin to hear each other. Maybe it begins with trying to please each other and also trying to let other people know you, not hide anything from them. whether it's, you know, anger or something you're ashamed of, or whatever. Actually, you should be relieved when other people know you. A sense of, actually, when you do have a sense of the way, when people find out you're dumb, it's finally a relief. At last they know I'm dumb.

[62:47]

All these years I wanted them to think I was smart. Now they know I'm dumb. So then you don't have to worry about it anymore. It's quite thrilling actually when people know you. But we're always trying to hide. And for us practicing together doesn't make any difference whether you're dumb or smart what your intelligence is. Your real intelligence is the ability to enter the stream of practice. All other intelligences are superficial. Is there anything we should talk about? Yeah?

[64:36]

Try to understand better what we mean by being aware. It's not... you know, aware is just a word, aware. What awareness is, is some wide range. So I can say aware, you know, A-W-A-R-E, but it doesn't communicate anything. The best way is to be someone's anja or jisha, actually. then you can begin to participate with somebody else, so you... No. Anyway, it doesn't mean judging.

[65:47]

It doesn't mean thinking or stopping it, or putting it in some idea, you know? As long as your mind sort of shapes things into little shapes, it goes ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch- So there isn't some you interfering, trying to see what it's doing, you know? As if you could. It's pretty difficult, I know that, it's pretty difficult. So easy to think we're doing it, you know? Not do it. But it's very visible in your actions. If your actions have a sense of being caught by being a particular person, it's clear you're not doing it. But anyway, don't worry about it. It takes quite a long time. If you persist over time... That's the third boon, patience.

[67:16]

I'm terrible about lists, I get them all mixed up. But I think it's third. Yeah. Can you hear what people ask? No? She said, what does our practice have to do with the war in Vietnam? What do you think? I don't know. I don't know. Meg said that if she is going to live in a world, I think I named, mixed up with, she said, if I'm going to

[68:42]

if she's going to live in a world where there's peace, she has to at least know what peace is for herself. That's true. Somebody at least has to know that. That's, anyway, each of your problems, and seemingly an insoluble problem. I know many of you know John Steiner. He... Let's see. I just talked about this the other day and I can't get it straight yet, but anyway. Tsukiroshi was talking about something or other. Rev, do you remember what Tsukiroshi was talking about before John said that? Well, during the questions. Earlier, Suzuki Roshi said it's not necessary to take part in demonstrations. Suzuki Roshi, of course, has marched in demonstrations in Japan and also in America with me in various peace marches.

[70:08]

So in this lecture, though, he said it's not necessary to participate in demonstrations. So John Steiner said, then what should we do about the war? Then what should we do? Then what should we do? John rephrased it. So anyway, Suzuki Yoshii came down and began beating him up. John, I don't know, at that point, John knew exactly what happened, you know. But all you can do in a situation like that is just, okay. But the problem there is, John, one, you should know what you should do. You should now be doing something with some confidence. Just be sitting, you know, thinking, what should we do or I ought to do. If you're practicing, you're doing, not ought to doing. Anyway, we're great. It's hard to see Zen Center from outside, since we're inside, but for a lot of people,

[71:35]

Sincere is something wonderful. I don't know. Lucky they don't come too often. But I know when I was in the East a few years ago, the director of Sane, you know what Sane is. I think it was Sane. said he'd given up trying to stop the war and the main thing that gave him hope for the future was the existence of Zen Center in Tassajar. Smile. Actually, I don't know if I believe that, but anyway. In some ways we do give people some confidence in that way, but that doesn't help your individual practice. or should you be, what can we do, you know? Actually, I think you can do anything. You can think of anything that's effective. I don't mean effective in, you know, that it's ending the war, but it's not just some idea or, you know, stewing in your own thoughts.

[72:55]

If you can think of anything that you can do or communicate, you should do it. But you should also practice. But our practice isn't... The more you practice, the more you realize our practice isn't our practice. but is shared by everybody. But you can't practice without that. So our practice extends to many people who do other things, whose job is to protest the war or to stop the war or to fight in the war even. Anyway, at least somebody should be doing what we're doing. What type of...

[74:34]

You know, this whole stupid history of dinosaurs and all that stupid, right? I just don't think so. And I'm saying we're part, living a part of a real trend. You know, we're just getting smaller, and, you know, it is part of ourselves, of anything. Especially in this country, which is changing. It's a small part of change. Why do we do this? Why do we have this sort of ailment? That's true. You know, why I'm up here is wrong. It's because there's a big fireplace under here. And it was too much work when we... This used to be the bar. It was down there, it was the bar. In fact, you may know the story. Just one year or two years before we got this place, a bunch of people were in here on horses, not in this room, but they came in on horses and they'd been drinking a lot. And they were literally, believe it or not, shooting the place up and making people dance.

[76:11]

You know, just like, pow, pow. And Bob Beck, who owned the place, got kind of upset. And so he phoned Bill Lambert, you know, Lambert's ranch. Bill Lambert is a deputy sheriff. So Bill Lambert immediately got in his Jeep and he raced in here. He walked in the door, which was down there, with a gun on each hip. He didn't draw them or anything, just a gun on each hip. And he said, OK, boys, put up the hardware. And everyone did, and he made an arrest and parted everybody off. Bill Lambert. I'll tell you one other story. No appropriateness, except it's about Bill Lambert. I just heard last week. I told that story, so this guy who was in here last week, I don't think he's still here. I think he went. Anyway, he'd just moved to Carmel Valley, and he'd only been here in Carmel Valley a couple days.

[77:43]

Justin moved in, he went into the... the stirrup? What is that bar and... the stirrup, something? I think it's called the... something, it's two words, but anyway, one of the words is the stirrup. He went in and the friend introduced him to Bill Lambert and said, this is my friend, this is... and Bill Lambert put his hand out and at the same time spit right in his shoe and said, and what are you going to do about that? This is a rather big young guy. Bill Lambert was a pretty old man at the time, 60 or something. So he said right away, I'll buy you a drink. Anyway, rather interesting man. He's been a very good friend of Zen Center's. Anyway, there's this big stone fireplace here. And we should take it down and tear it up and lower this, you know, but ideally we would lower this somewhat and raise all of these so we're all on the same level. I know what your question is.

[79:08]

what Buddhist music is and mokugyo, etc. I don't know, that's too long to talk about. But why we have... If you don't know what your history is, you just are caught by it. You think you can just participate in the present. So our actual backbone is, you know, our lineage. all those Dayasuras. There's nothing special about it. So there's two things we look at. What happens simultaneous with us? And our lineage and what that means is very important. I mean, I don't know, it's not easy to explain.

[80:39]

Buddhism actually doesn't exist. You all know that. But there's nothing we can say about Buddhism, actually, particularly if I try to say in my own words, that won't confuse you. You can't talk about it. What Buddhism is, nobody can say. You can't name it. But the way of the Buddhism patriarchs, The patriarchs left us, you know, this lineage, left us many ways to teach. So, to use what they left us to help teach about Buddhism is not to mean that what they taught is Buddhism.

[82:12]

Anyway, it's just some help. Those people, we shouldn't have the idea that they are less real than the person sitting next to you. Actually, Suzuki Roshi isn't here anymore, but he's more real than the person next to you in many ways. If you have some idea of reality being, you know, that actual physical thing only next to you, that's not what we mean. Anyway, the kind of questions you ask are excellent, if you can really ask them to yourself. Thank you.

[83:51]

@Transcribed_v004L

@Text_v005

@Score_49.5