Living Wisely Through Daily Choices

Welcome! You can log in or create an account to save favorites, edit keywords, transcripts, and more.

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk focuses on the manifestation of wisdom in daily life, particularly through moderate living and the management of relationships. The discussion draws heavily on teachings from Sirach and other biblical wisdom literature, highlighting practical daily choices involving eating, drinking, and possessions, emphasizing discernment, moderation, and generosity as key to living well. It further explores the implications of murmuring and grumbling within monastic and community life as obstacles to contentment and spiritual growth.

Referenced Works:

- Proverbs 8: Discussed as a source of wisdom, highlighting the importance of daily vigilance in seeking a life favored by God.

- Sirach (Ecclesiasticus): Cited extensively, offering practical advice on daily life, moderation, and the importance of generosity; particularly chapter 29 on life's essentials and chapter 31 on table manners.

- Book of Tobit: Mentioned in connection with the theology of almsgiving, reinforcing the wisdom found in generosity.

- Rule of Benedict: Referenced as a wisdom text that emphasizes moderation and the daily needs of monastic life, underlining the importance of community and the avoidance of grumbling.

- Proverbs 30, Wisdom of Agur: Invoked to illustrate the wisdom of seeking neither poverty nor excess, but a balanced life.

- John Cassian and the Desert Fathers: Alluded to in discussions of asceticism as the practice of taking only what is needed.

- Kohelet (Ecclesiastes): Its message of enjoying present blessings while maintaining gratitude to God is noted.

- Columba Stewart's article on asceticism: Cited to underscore the idea of taking only what is necessary as true asceticism.

- Diane Burgant's article in Bible Today: Titled "Sirach, Blessed are the Not So Poor," it presents Sirach as a guide for middle-class wisdom, exploring daily decision-making and moderation.

AI Suggested Title: Living Wisely Through Daily Choices

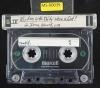

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

Speaker: Sr. Irene Nowell, OSB

Possible Title: Wisdom in the Daily: Where is God?

Additional text:

@AI-Vision_v002

Mar. 25-28, 1995

God of our ancestors, Lord of mercy, you who have made all things by your word, with you is wisdom who knows your works and was present when you made the world, who understands what is pleasing in your eyes and what is conformable with your commands. Send her forth from your holy heavens and from your glorious throne dispatch her, that she may be with us and work with us, that we may know what is your pleasure. Well, we've looked at wisdom. We've looked at wisdom as the tree of life and wisdom as the word of God, but it's Monday. And so today we're going to come down to reality. We've looked at some pretty high-powered concepts, and today we're going to look at wisdom in the daily.

[01:02]

Where do we really have to deal with these choices? Where do we get to find wisdom? Where do we find this tree of life, this tree of the knowledge of good and bad in our lives? And it's in the daily. In Proverbs 8, wisdom says, happy the one watching daily at my gates, waiting at my doorposts. The one who finds me finds life and wins favor from the Lord. So where do we find wisdom and where do we find God? It's in the story of our daily lives. Every day we choose. And that's really our daily vow of conversatio. I think, at least for my money, the central monastic vow is conversatio.

[02:04]

That's the one that daily comes back to us. So what is daily? What's daily in our lives? Sirach says in chapter 29, life's prime needs are water, bread, and clothing, a house too, for decent privacy. So he kind of lays out the essentials. Water, bread, and clothing, and a house too. eating, drinking, clothing, shelter. And then he goes on to say, better a poor person's fare under the shadow of one's own roof than sumptuous banquets among strangers. And so, the freedom and independence of at least having something of our own space. Our own daily choices are in these things. Where is wisdom?

[03:05]

Where is God? It's in eating, drinking, clothing, shelter, freedom, independence. And how do we find wisdom? In these things. In these things that we do every day. Ben Sira gives us a whole collection of advice on these things. Diane Burgant, in an article on Sirach years ago in Bible Today, called Sirach, Blessed are the not so poor. And she said, it's a wisdom of the middle class. Obviously, Ben Sira is addressing his advice to people who have something. And so he gives advice about all these things that we have in our daily life and all these things that present choices to us. In chapter 31, he has that wonderful section on table manners, and it certainly tells us that the wisdom writers are interested in common human experience, that the basis of this is common human experience.

[04:21]

I think we don't often think that God is a lot worried about our table manners or whatever like that. Although I confess that my novice director was very worried. She told us when I was a novice that we had the worst table manners of any class she'd ever gotten. But I've learned later she told every class that. And I hear from the current novice director it's getting worse. But somehow it's in those daily choices, and that's a good example because we eat every day. Now, I don't know if you had a chance to look at Sirach 31, but it's wonderful. He says, if you're dining with somebody, great. Don't go hungry. Well, Scarlett O'Hara got that same advice. You know, she had to eat before she went out to this party so she wouldn't look greedy. Don't cry out. How much food there is here. Remember that gluttony is evil.

[05:25]

No creature is greedier than the eye. Now there already in the second century is our eyes are bigger than our stomachs. He gives lots of advice about don't eat too much because you won't be able to sleep well. Now again, notice this is based on common human experience. It's not that God says, you know, be moderate. It's that you're not gonna feel good if you eat too much. And he also says, don't drink too much. Because if you drink too much, let not wine drinking be the proof of your strength, for wine has been the ruin of many. Wine is very life to persons if taken in moderation. Joy, good cheer, merriment are wine drunk freely at the proper time. Headache, bitterness, and disgrace is wine drunk amid anger and strife. Isn't it the truth?

[06:29]

As one of our older sisters says, isn't it? There's wisdom in our daily lives. Now I confess that only Only once in my life have I drunk so much that the next morning I really was sick. We had a Semitics party, Brother Aloysius, your good friend, and the cook, who was from Iraq actually, we were in a new place and he wasn't used to the Kitchen and so dinner was later well we started with the good scotch and then we ended with the bad scotch and then we switched to sangria and My sister's with whom I lived that year said when I got home all I could say was it was such a nice party But the next morning I felt pretty awful and I Learned Headache, bitterness, and disgrace are how you feel.

[07:31]

It's just plain good advice. Where is wisdom? It's in the daily. You have to make those choices. I also confess that more often than that I've been in a situation where it was hard to sleep because of what I had eaten. But notice what Ben Sire is saying. Enjoy the good life. The goal of wisdom is the good life. And to live well means to be healthy. And to be healthy means that we have to eat and drink in moderation. He's not saying, don't eat, don't drink. He's saying, be careful, otherwise you can feel awful. Back in chapter 29, he talks about, now this is talking about people who have something. He's talking about loans. What do you do with your money? Well, he says it's a good idea to loan to your neighbor, but a few verses later he says, you know, it might not be a good idea because when you loan to somebody, if the lender is able to recover barely half, he considers this an achievement.

[08:46]

If not, he is cheated of his wealth and acquires an enemy at no extra charge. Again, there you are. It's the truth. This convinces by its very truth. But then he goes on to say, to the poor, however, be generous. So if you're dealing with somebody on a regular business level, be careful. But to the poor, be generous. Do not keep them waiting for your alms. And then he says, spend your money for your brother and friend and hide it not under a stone to perish. Dispose of your treasure as the most high commands for that will profit you more than gold. So he's not recommending miserliness. In another place he says there is no one stingier than the person who is stingy with herself or with himself. So use what you have for the good life and use what you have

[09:52]

to give to the poor and spend your money for your brother and friend. So again, it's good advice. Store up almsgiving in your treasure house and it will save you from every evil. better than a stout shield and a sturdy spear, it will fight for you against the foe." Actually, the whole theology of almsgiving in the Old Testament is in the book of Sirach and the book of Tobit. Apparently, right in that period, just around 200 to 180 BCE, this theology of giving alms and that alms were worth more than sacrifice developed. And if you're looking for almsgiving texts, Sirach is your spot. Now, possessions or the lack of possessions can be a burden and can be a detriment to the good life. Having too much is a detriment to the good life.

[10:54]

Not having enough is a detriment to the good life. you all probably don't move as often as some of us do. You know, we move at least from one place to another in the monastery or from Antis into Kansas City or wherever. Moving is a real test of how much we acquire. Moving, suddenly all those books that fit on the shelf fit in a lot of boxes when one moves. Moving, dusting, finding, Dan Ward says that the whole reason for simplicity of life in monastic life is so that we can listen. He says that the first word of the rule, listen, is the key, and that when we have too many things, they distract us and we can't listen. He also says that the younger folks in monastery need more possibility for acquiring things because they haven't acquired as much as the older among us have.

[12:06]

But anyway, the whole idea of the simplicity is not to deprive ourselves, but so that we can listen. And Ben Cyrus says we need to be content with what we have and that we need to be able to give to others and that all of it we recognize is a gift from God. So where is the wisdom? The wisdom is in the knowledge of good and bad. And there's an ambiguity there. Because too much good is bad. Too little good is bad. So the discernment, the evaluation, is in the moderation. And of course we know that that's a primary value in the rule of Benedict. Columbus Stewart from St.

[13:10]

John's, you may know him, he's a It does a lot with the Desert Fathers and John Cashin. But Columba, in an article on asceticism, says that asceticism, the true asceticism, is taking only what we need. Now that's a real challenge. Taking only what we need. It's so much easier to say, I won't take any. or to say, it doesn't matter, than to simply, day after day, take only what we need. There's no drama. There's no glory. It's simply taking what we need. That is genuine asceticism. It's certainly counter-cultural. Our whole culture is built on a notion of consumerism that more is better and if you have the right one it will make you wonderful and happy and so on.

[14:22]

But the notion of simply taking what you need and no more is a genuine counter-cultural witness And it certainly is part of what wisdom is teaching us. In Proverbs, Proverbs chapter 30, it's in the wisdom of Agur. There's a phrase that says, give me neither poverty nor riches. Provide me only with the food I need. Lest, being full, I deny you, saying, Who is the Lord? Or, being in want, I steal and profane the name of the Lord my God. Give me neither poverty nor riches." Now, that's a real monastic sentence. In my house, in the

[15:25]

late 60s, early 70s, we were, you know, that was kind of the peak for a lot of us, and we were doing pretty well in the late 60s, early 70s. And so we, in our fervor, some of those of us who were among the younger sisters then were saying, well, you know, we ought to do what the Tay-Zay community does, that whatever we have left over at the end of the year, we should give away. which is certainly a noble idea. Well, we've laughed a lot since then because now with fewer numbers, older sisters, buildings, etc. The surplus got taken care of. We didn't have to worry about it. We don't have that extra anymore. We didn't have to give it to anybody. It just went. But I remember when we were talking about that, one of our really wise middle-aged sisters said, we're not Franciscans. The notion of poverty is not the point. It's the notion of moderation that is important for monastics.

[16:27]

We have what we need. for the good life. Give me neither poverty nor riches. Provide me only with the food I need. Lest being full I deny you, or being in want I steal." So asceticism is taking only what we need. Now, We know one of the real glories of the Rule of Benedict actually is this attention, this is part of why it's a wisdom book, is this attention to the daily, to daily needs, and the attention to moderation. Benedict spends several chapters talking about eating and drinking. We're supposed to have the proper amount of food. We're supposed to have a couple of dishes in case somebody can eat.

[17:31]

If they can't eat one, they can eat the other one. If there's more available, you could have a third dish. You know, Benedict is not saying, don't take it, but take only what you need. If the work is heavier, eat more. However, Above all, overindulgence is avoided. And why? Lest a monk experience indigestion." Now there he's coming right out of Sirac. Don't eat too much, you're not going to feel good. And then he even takes care of the young and the old and the sick. And then I think one of our favorite chapters is the chapter about the proper amount of drink. And he says, you know, it's hard to specify this for other people. And he really thinks monks shouldn't drink.

[18:32]

But since we can't be convinced of this, at least we shouldn't drink too much. Now there's the moderation again. And the superior determines when we need less and when we need more. However, the superior must in any case take great care lest excess or drunkenness creep in. And the chapter ends with, above all else we admonish them to refrain from grumbling. In the old translation it was murmuring. And even the chapter on the times for our meals takes into account, remember wisdom is in that intersection between the wisdom principles and the reality of our daily life. And so when it's hotter, we eat at different times.

[19:33]

When it's lighter, we have a different schedule. However, All of this should be arranged so that we may go about our activities without justifiable grumbling. The refrain that comes back over and over in these chapters is not to grumble, to be satisfied with what we have, but the refrain also that comes back is that it should be arranged so that we have what we need. And in relationship to possessions, first of all, the tools of the monastery are entrusted to whoever needs them. But we're to treat all these things as vessels of the altar. And so the real respect for things or not to own anything.

[20:35]

Everything is to be in the common possession of all. No one presumes to call anything his own. However, that has to be read in connection, then, with the next chapter. Distribution is made according to need. So it's not that we have nothing. It's that we have what we need. It's the wisdom principle, take only what you need. And whoever needs less should thank God, and whoever needs more should be humbled because of weakness. And guess what? First and foremost, there must be no sign or word of the evil of grumbling. If anybody is caught grumbling, then let that person undergo more severe discipline. It doesn't end up if anybody is caught taking more than they need, if anybody is noticed to be grumbling. It's the grumbling that's destructive.

[21:37]

Now, murmuring has a long biblical history. I used to tell my college students that if they remembered anything at all about the desert period, the period between the exodus and the entrance into the land, they should remember murmuring. That the community of Israel is dragged kicking and screaming all the way across the desert into the promised land. They start out at the very beginning before they ever cross the sea and say, you know, we wish, we were happy being slaves. Why did you deliver us? And weren't there enough graves in Egypt? Couldn't you let us die there?" And God says to Moses, you know, stretch out your hand across the sea and ask for the people they have only to keep still. Now, big challenge, no murmuring. Now, of course, they're barely across the sea, they sing the song, and the next thing they're grumbling because they don't have any water. And then they're grumbling because they don't have any food.

[22:44]

My image of the desert period is like driving across the country in a station wagon with too many kids. It's the best image I have. You know, I'm hungry. I'm thirsty. Are we on the right road? Are we lost? Why did we leave home? All the way in the desert, the murmuring continues. And if you really look at it, it's really a crisis in leadership. Where there's murmuring, it's a crisis in leadership. First, they murmur against Moses, but they're really murmuring against God. You know, we remember the leeks and the onions and the garlic and everything else we had in Egypt. Why did you deliver us? Why were we redeemed? We were happy eating in Egypt. So it's almost the same kind of grumbling that you find in Genesis 3, when God says to the human being, what have you done?

[23:47]

And he says, this woman that you put here, It's the initial passing the buck, but it's passing the buck not only to the woman, but to God. You know, I was happy in this garden until she came. And it's your fault. You put her there. So the crisis really is a murmuring against God. Why did you bring us out into this desert? Now, there's a lot of connection between monastic life and the desert. And that's why Benedict spends a lot of time talking about the evil of grumbling. One of the things that recurs again and again and again in the wisdom literature is that everything we have is a gift from God. Above all, and this is after all of these things about how nice it is to have a good dinner with music and wine, Above all, give praise to your Creator, who showers favors upon you."

[24:49]

It's all a gift from God. That's Kohelet's main message in the Eat, Drink, and Be Merry. He says, all we have is the present moment, and that's a gift from God, and we should enjoy whatever it is that God gave us in that present moment. Eat, drink, and be merry, and give thanks to God. But above all, don't murmur. Now there's one more chapter in, and there are a lot of chapters, in the rule that talks about the daily. But a chapter that takes a little bit of a different turn is chapter four, the tools for good works. Now, the Tools for Good Works is kind of Benedict's Book of Proverbs. It's a whole collection, you know, of little sayings, and they have to do with daily life. They begin with, love the Lord your God and love your neighbor, and then they go through the commandments, but then it's your attitude throughout life, and lots of little

[26:00]

little advice, and I don't know if I told all of you, but the saying that's been stuck to me ever since I was a novice was, never despair of God's mercy. Once you get to the end, that's the real clue. But at the end of that chapter, it says, these are the tools of the spiritual craft. When we've used them without ceasing day and night, and have returned them on Judgment Day, our wages will be the reward the Lord has promised. The workshop where we are to toil faithfully at all these tasks is the enclosure of the monastery and stability in the community." Now, Pearl Bailey says, the trouble with life is it's so daily. And sometimes that's the trouble with monastic life, is it's so daily. But that's where God is, that's where the wisdom is, that's where the moderation is.

[27:02]

That's why the murmuring is such a problem, because it drags down the daily. Chapter 4 has A lot in it about relationships, beginning with loving God and loving neighbor, and then our attitudes toward each other. Never do to another what you do not want done to yourself, and so on. One of the other things in our lives, besides eating, drinking, clothing, shelter, material goods, one of the other daily things is our relationship with each other. It's the gift of community, and community is a gift, even though in the daily some days it doesn't seem like it. I don't know about you all, one of our younger sisters says I saved her vocation the day I came to breakfast and said, I looked across the chapel and thought, I don't even like any of these people.

[28:09]

Now, most days I love my sisters, but there are days I think, why am I here with all these people? And yet, I cannot imagine my life now separated from them. My life has become so woven with their lives that I don't know what it looks like if I'm not a part of that community. Sirach has some things to say about that dailiness. He has, again, probably more texts about friendship than any other biblical writer. Now, Sirach is a cautious man, and so he's very careful about testing friends. But he says, for instance, in Chapter 6, he tells us how to acquire friends.

[29:12]

A kind mouth multiplies friends, and gracious lips prompt friendly greetings. But then he says, let your acquaintances be many, but one in a thousand your confidant. And so friendship is a real treasure. A faithful friend is a sturdy shelter. The one who finds one finds a treasure. A faithful friend is beyond price. No sum can balance his worth. A faithful friend is a life-saving remedy, such as the one who fears God finds. For the one who fears God behaves accordingly, and his friend or her friend will be like himself. So how do we manage this dailiness? It's because of the friendship and the relationship and the support of the community.

[30:13]

In chapter 9, he tells us to treasure our old friends. Discard not an old friend, for the new one cannot equal him. A new friend is like new wine, which you drink with pleasure only when it has aged. And so the gift of stability and community is that we become old friends. And in chapter 37, he gives us some advice in verses 12 to 15 of that chapter. And this, I think, really is the rule of thumb of how to live a daily life, how to have the strength to live a daily life. He says three things for us. associate with religious persons who you are sure keep the commandments, who are like-minded with yourself and will feel with you if you fall, or feel for you if you fall.

[31:24]

Back at the beginning, you were talking about compassion. Now, he says in several other places, the thing that we all learn from our mothers, you know, birds of a feather flock together and so on, that if we associate with believing and who have compassion if you fall. Now that's a wonderful description of what community life can be. Secondly, then too, heed your own heart's counsel. For what have you that you can depend on more? A person's conscience can tell him his situation better than seven sentinels in a lofty tower. So first, associate with faithful people. Secondly, listen to your own heart's counsel, your own conscience. This is the daily life. And thirdly, most important of all, pray to God to set your feet in the path of truth.

[32:30]

Now, wisdom is in the relationships. The relationships with each other, our relationship with ourselves, and our relationship with God. And that's our daily life. Our daily life is woven out of those three relationships. This really is what wisdom is, and if you go back and think about those folks we talked about as wise on Saturday night, it's the folks who know how to live well in their daily lives. So, Well, I think about that a minute and then we'll see if there's anything anybody wants to say about either what we've talked about this morning or if you've got something left over from last night. I didn't give you a chance last night, so...

[33:33]

Any daily thoughts? I really can't believe, so in other words, so my religion, my taking responsibility I think so. That's a good way to put it. I think so. Because it really is kind of abdicating that responsibility. It's always somebody else's fault if we murmur. Joan Chidester tells a story about the beginning of renewal, the beginning of those years. And Joan said she went home to her mother for a visit. And she said, well, Mom, religious life has fallen apart.

[35:12]

The whole thing is just collapsing, and people are leaving, and all of that. And she said, it's just not going to last, and so you might as well get ready for me to come home. And her mother, you know, her mother said, well, what are you doing about it? And Joan really credits her mother saying that with the whole kind of energy that she's devoted to what religious life is in the last 20 years. So it has to do with that taking responsibility, I think. That's right. It is very difficult. You're right. Yeah, it's much easier to think about something else or look at somebody else. Yeah, I think that's part of the asceticism too, is to do what we're doing. I'm terrible at learning, and I'm still struggling with this, at learning how to be in the present.

[36:22]

You know, I spend a lot of time a week from now kind of planning what's going to happen next, and it's a real struggle for me to stay in the present moment. It's an explanation really of taking what we need. I was robbed three years ago in my apartment at gunpoint by this young man, two young men, and a very frightening situation. And at some point... I'd have been out on the floor. No, I was there. Why don't you just take what you need and go? I'm not going to do anything. And I don't think I understood what I meant. So I was wondering, I'm wondering about this take what you need. How do you tell this to people who need everything in a situation like that?

[37:28]

I mean, I'm thinking of the wisdom that you taught. And I don't know that we can tell anybody, in a sense. I think that is such a radical sign of trusting in God, to take only what we need. that I think somehow we have to, I think it's connected to the, you know, not in your situation with being robbed at gunpoint, I think all you do is thank God that you didn't get shot, but it's only when people begin to learn that God and we, through us, provides for their needs, that that kind of faith can happen. Because we are also insecure, you know, we want to protect ourselves.

[38:34]

And of course, if they're in whatever situation leads them to do that, they need everything. This is not a help, but this is kind of throwing something at that question. There's the story in the desert, one of the manna stories, where, it's a priestly story, you can tell because of the emphasis on the Sabbath, but they're supposed to gather the manna, you know, just enough for one day every day, except on the sixth day, and they're supposed to gather enough for two because of the Sabbath. Well, when they're just supposed to gather enough for one day, you know, somebody, of course, Figures, you know, as my grandmother would say, if one's good, two's better. They gather enough for two days. They won't have to go out for the second day, and it rots. And we say in the Our Father, give us today our daily bread. And that's not to say we don't figure out how prudently to take care of ourselves.

[39:43]

I mean, I think that's wisdom, too. But there's something about hoarding, too, that is the fear that we won't be taken care of. I think it really is fear. I don't know. What do you think? My feelings right there is that the two guys, they needed everything. They didn't even know what they needed. They needed including to take my wife away, take my wife because they're ready. They're just about to do it. Then I got what I needed at that point. California Brangham was my mother. God bless her. Oh no. That's a wonderful... And then she was trying to call, and they had to pick up the telephone. And for a moment they put it back, and then she said, what's happening? The party's so exciting that nobody can answer the phone. He told one of them, and because Shabbat was near, so, well, it's his birthday, we've got to get out of here, because there might be people coming.

[40:52]

So they left. Shortly before, one had told the other, the night is there, you know how to do it, you know how to kill someone. One told to the other. So I got what I needed, but I knew that these people, I never found myself in a situation where dealing with this kind of, with need, and you can barely understand what is it you need. I was ready there in order to protect my life, to give whatever was asked, but I couldn't I'm not talking about immigrants that came from Cuba or Puerto Rico and faced a difficult situation. I'm talking about people who are always poor. They don't know anything else but poverty. So, I mean, this is what I was thinking. How do I tell this kind of person? Take what you need. If they don't know. If they don't. And they don't know.

[41:53]

They don't know. Yeah. And that's, I mean, that's why it's such a countercultural witness if we can somehow try to live that way. To say, you know, you could live without some of these things. But our whole culture is set up to tell people they need everything. Because people will, well, like the looting, you know, after the, in Los Angeles, well, in Los Angeles, anywhere, you know, when there's a disaster, people loot. And the, people getting killed for starter jackets, you know, because somehow they need them. It's, yeah, our whole culture is set up to create needs. My mother used to write advertising, and she said one of the basic principles they teach you is to create need. So it's a really, it's a hard situation.

[42:54]

And on the other side of it is how do we... I think we can only do it by the way we live ourselves, but shalom in Hebrew really means the situation in which everyone has what is needed for a full life. So it's not just the absence of conflict, it's that everyone has what is needed. Now obviously it means then that the moderation in the, somehow in the trust. But I, yeah, I don't know. Oh, what you say about the contrast between the poverty of the Franciscans and the Catholics of Saint-Laurent. Our founding father was superior, what you perceive your father. was one of the dynamists of the German regime about Maria Lack in Germany, and I guess he was a disciple of the Atlantic Air League, and Rahid's emphasis was on Parshitas.

[44:07]

But of course, it was a term that just raided the whole community at one time. But again, it got to be abused, because somebody would put a little more hool on your plate than somebody else. And he would, and your neighbor next to you might say, Posse cops. There you got the grumbling. Yeah. Too much Posse cops. Turnips go all the way down the table And our toothbrush Aren't we human? That's true. And it's, you know, it's the daily.

[45:13]

I think this has to do with the grumbling too. It's in the daily where we fall into that problem of judging each other, you know, that we were reading about. I was starting to read the gospel for next Sunday. And it's the story of the woman taken in adultery and Jesus says, you know, if whoever is without sin cast the first stone. And I thought, you know, It's the things that are my own faults that I judge in others. You know, things that are not my faults, but that I see in others, it's easy to forgive. But if it's something that I struggle with, you know, it's much harder. But that judge, it's the grumbling and the judging one another in that. That's a wonderful story about the Rossi dogs. Yeah. Well, the next item on the agenda is the mystery of suffering, and I think perhaps the daily life leads us to that as much as anything.

[46:27]

So, we'll end with this little prayer to wisdom. O wisdom proceeding from the mouth of the Most High, announced by the prophets, come, teach us the way of salvation. Come, Lord, come to save us.

[46:48]

@Transcribed_v004

@Text_v004

@Score_JJ