You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Zen's Cross-Cultural Wisdom Journey

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk discusses the relationship between East Coast intellectuals and Zen practice, noting a sociological contrast with West Coast practitioners drawn to Zen through direct engagement with Zazen. It emphasizes the importance of cultural practice and introspection, drawing lessons from historical Zen stories to highlight the necessity of strict personal discipline and community self-sufficiency in addressing contemporary cultural challenges.

- Seppo and Ganto Story: This tale from the Tang Dynasty exemplifies Zen's resilient practice during periods of persecution, focusing on creating personal understanding internally rather than relying on external conditions. It illustrates the importance of personal insight and self-reliance in Zen practice.

- Avalokiteśvara Metaphor: Used to demonstrate adaptable practice, suggesting that Zen teachers must meet students where they are, reflecting their needs and backgrounds in teaching methods.

- Dogen Zenji's Teaching: Stresses integrating cultural and individual practice, with Zen evolving from cultural context while returning to early Buddhism's core ethos.

- Bodhicitta and Vows: Explored as foundational elements in a bodhisattva's journey, emphasizing the interplay of personal enlightenment with cultural predispositions and thorough preparation.

- Ecological Thinking and Buddhism: Integrates contemporary ecological awareness with Zen philosophy, as exemplified by figures like Charles Lindbergh, indicating shared values between ecological activism and Buddhist insight.

Each of these points illustrates how the integration of cultural, historical, and personal elements shapes the practice and understanding of Zen in diverse contexts.

AI Suggested Title: Zen's Cross-Cultural Wisdom Journey

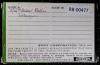

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

Speaker: Baker Roshi

Location: Tassajara

Additional text: Z.M.C.

Speaker: Baker Roshi

Location: Tassajara

Additional text:

@AI-Vision_v003

As many of you know, I just went to the East Coast for about two weeks. Can you hear me in the back? I mean, yes, in Japanese. I went to Vermont first to marry Peter Schneider and Jane Brunt, and then we went to several other cities. One part of Zen Center that nobody knew much about except myself is all the people on the East Coast who feel very close to Zen Center. And so I brought Yvonne because she's the president now. I'd made this kind of trip

[01:03]

with Suzuki Roshi, but never before has anybody made it with me. So I brought Yvonne to introduce her to those people in the East. And so now all parts of Zen Center somebody knows, so I don't have to do it. And after next week, I guess you know, Sunday and Saturday, I'm going to Japan for about two months to do some things that Suzuki Roshi wanted me to do and to pack our house up, which is going to be torn down in Kyoto to make way for apartment building. I guess half the garden is already gone. But we came back so quickly last fall that we didn't have time to

[02:07]

move actually out of Kyoto. After coming back from Japan, I'll come here for the practice period. The trip to the East Coast was very interesting because the people there, most of the people I saw are quite different from our students. I mean the students here, there's no particular or easily definable sociology of why you're all here. Mostly you're here because you like Zazen. I think some of you because you've read books and other things, but just as many people have read books leave too. But mostly it's because you like Zazen. But on the East Coast, there's a kind of very clear sociology. And partly it's that

[03:15]

Suzuki Roshi from the beginning, many artists and writers and painters came to Zen Center. There's some community that Suzuki Roshi felt with artists and with the beat scene and with several themes in our culture which led to Zen. As I said to someone today, the Hasidic tradition and the New England transcendentalism, many such things. And in contrast to the West Coast, in the East, it's the real establishment of this country. Not the presidents of companies, but the owners of companies, or rather the people who wish they no longer owned companies, who would like to get rid of what they have. And every place we went, we would just stop to say

[04:20]

hello to somebody, and we'd find they'd gathered this extraordinary group of people who is the largest one who is the largest taxpayer in Massachusetts. Another who's head of the Lincoln Center, financial side. Or General Lindbergh, Charles Lindbergh. Many, many people, you know, I can't want to mention all of them. And what was characteristic of them all is they all felt like they were Buddhists. And Buddhists because they have everything this country, our culture, has to offer. And they don't feel it's enough, you know. Or they don't feel right about the way the world is, or their possessions. And, of course, ecological thinking is very important now. Lindbergh is completely involved in thinking ecologically, which is very close to Buddhism, almost exactly the same. Also, they all related. They all have a sense of some kind of transition

[05:33]

the world's going through, this country's going through. And, you know, Buddhism goes through, has gone through many steps, kinds of development. And with Dogen, you have a kind of Dogen Zenji who began, brought this particular way of studying Zen to Japan, and also gave it a kind of sense. He, in many ways, intuitively brought Buddhism back to early Buddhism. But also with Dogen, he rec... Zen becomes very cultural, in the sense that it doesn't just emphasize your individual practice. It emphasizes practicing your whole culture, that you are your culture. When you practice, you practice your culture. It's interesting, because in some ways this is the beginning step in Buddhist practice.

[06:47]

You know, if you know in sutras, they say, sons of good family, something like that, breeding. What this really means is a whole background about that phrase. It means that before you can have the thought of enlightenment, which generally begins the career of a bodhisattva, you have to have a predisposition to this possibility. And in traditional cultures, it meant that you had to have some education and leisure and such things, which only went usually with privilege. In this culture, I think that that kind of intelligence or sophistication is much more widespread, I think. Now Zen, as a way of knowledge and practice, is not going to be just for an elite, as it has been in other cultures. But this predisposition has a lot to do with where you are in your culture and how you practice your culture, and how your culture prepares you for understanding Buddhism. So many of you are actually at that stage of

[08:01]

practice. The kinds of questions you ask, what do I do with evil desires, and how do I, well, how can I say, you know, if you hit the bell, you know, or drum, you hit the drum or bell just right. And if you don't hit it right, or you have some tendency to hit it too loud or something, that's like the beginning stage, you know, when you have problems with being in harmony with things. So a lot of your problems are to do with, are problems I could do with, I was too angry, or I was short-sighted in how I treated people, or something. But then practice brings us to, prepares us for a critical moment in our life. And maybe each

[09:05]

moment is the critical moment, actually. Just to hit the bell just right. Or if you're like Suzuki Roshi, to know by one glance what to say to a student, how to react to a student. Just to look, to be able to look. So for these people I'm talking about in the East, what they see is a critical moment coming in our culture. And Suzuki Roshi felt that too. As I may have said to you, he felt that America was having quite a kind of crisis or nervous breakdown. It may get

[10:05]

worse and worse. And the people in the East had the same kind of feeling. They want to do something to help. They were quite moved by what we're doing. They don't see it from the inside, so they don't know how many problems we have. It looks good from the outside. But part of what we're trying to do is find out not only how to be individually self-sufficient, but also as a community to be self-sufficient. So this is one of the reasons we have Green Gulch, to find out how to grow our own food. But we don't want to be self-sufficient in the sense that we're not dependent on others. That wouldn't be our practice. I know at one point when students wanted to start

[11:09]

a bookstore, Roshi got rather angry and said you should buy from the local bookstore. He needs the business. So we're not trying to, by growing our own food, become not dependent on others, but rather to have some experience in how to take care of ourselves completely. Suki Roshi even felt that this kind of community may be an island, if this country has a very difficult time. Individuals who are together, and the community which is together, both may be a kind of island. Because your culture must start from within. You must create yourself from within. We must create Zen from within. And then it doesn't make so much difference what happens. Because this kind of

[12:10]

creation is imperturbable. Our mind should be imperturbable. So in practice we should be strict with ourselves in order to prepare for that kind of critical moment. One of Roshi's favorite stories was about Seppo and Ganto. And I think I talked with you about it, because Seppo and Ganto are so important in the Tang Dynasty Buddhism and in the Blue Cliff Records. So I'll only tell a short

[13:17]

version of Seppo. Seppo is an example of hard practice for Zen students. This was at the end of the Tang Dynasty. There was quite a lot of persecution of Buddhism at that time. You can't remember the reason, but I think that Buddhism became too rich. You know, Buddhism gets quite successful and ends up owning all the gold and copper and bronze. Then the emperor doesn't have any guns, you know. So he has to raid the temple to get the metal back. I mean, that kind of thing happened. Anyway, there was quite a lot of persecution. And most of the Buddhist sects that were dependent on buildings and scriptures disappeared from China for some time. But Zen,

[14:25]

which had created its own culture from within, was not harmed too much. It actually was strengthened. And many people lived in the mountains or in retreats in small groups, practicing. Anyway, the story of Seppo and Ganto is they were crossing a high mountain and they stopped near the summit to pass. And Ganto fell asleep right away, but Seppo couldn't. He kept sitting up by the fire. Finally, Ganto woke up and said, what is the matter? And Seppo said, I've visited Tozan nine times and I've done this and that. I was enlightened under so-and-so, etc. And still,

[15:33]

something in my mind is not clear. I'm very depressed. And Ganto said, you can't depend on things from outside of you or what other people say. It has to come from... You have to let your own nature do it. Generally, we know ourselves objectively, but not subjectively. Anyway, whatever Ganto said to him supposedly enlightened Seppo at that time. And this kind of practice over and over again was what Suzuki Roshi emphasized. And this experience from Tang dynasty, which was a very long time ago, until quite recently, for instance, this practice

[16:37]

continues. Suzuki Roshi's teacher and master, Kichizao Roshi's teacher. I can't remember his name. But anyway, he was going from his temple over Hakone Mountain, I think, which is quite a difficult mountain to cross over on the Tokaido Road. And he came to this temple where he asked to stay for the night at Ohara or Odara. I can't remember. His story is from 1962. Anyway, he went in and he asked for lodging. And he was quite a vigorous young man. And this man at this temple, which we'll say at Ohara, saw this young man. He acknowledged him. After this stage of what your

[18:00]

disposition is, or breeding, or preparation, there are three important factors that begin knowledge of bodhisattva's career. One is the thought of enlightenment. The second is vows. And the third is a prediction that you'll achieve enlightenment. The thought of enlightenment, bodhicitta, has many meanings. But somehow it comes about when you see somebody like Suzuki Roshi, maybe. Then you take vows and make that firm. That's quite a long process, actually. And at some point you're acknowledged. Anyway, this monk, this teacher at this temple, saw him and had some feeling about him. So he invited

[19:10]

him upstairs. And after he'd gone upstairs, he took the ladder away and said, you just stay there and I'll give you everything you need. And I guess he kept him up there several months. And he practiced zazen upstairs. And this man was so strict at this temple where he'd happen to take lodging that nobody stayed with him more than a few months. But this man, Kichi Zawa Roshi's teacher, stayed for many years. And then afterwards walked, even after he left and had his own temple. He would walk 25 miles over the mountain to see him and 25 miles back, twice a month or something. Anyway, he never gave me an opportunity to practice like that. I

[20:18]

always drive to temple. But we used to talk about having a path. Maybe we should do that. But to create hardship is not the point. Actually, if you're strict with yourself, there's enough hardship. Coming back from the East Coast where Suzuki Roshi used to say that Avalokiteśvara has a thousand arms.

[22:07]

And for a thief, he appears as a thief. For a sailor, he appears as a sailor. For a businessman, he appears as a businessman. So when you're seeing people like that, you can't always be sort of sitting very straight. It makes people nervous. So if it slouches, you have to slouch. And if people wear suits, you have to wear suits. You don't have to. You can wear robes. Anyway, but I make that kind of transition. It's okay. But it's a relief to be back here where I don't have to do that. We have a wonderful place to practice here, Tassajara in San Francisco. I felt that very clearly when I came back from being in the East.

[23:20]

Yeah. There are many stories about seeing yourself subjectively, not objectively. So somebody says, Who are you? And someone answers, Just the person you see in front of you. But, so the teacher says, I think a donkey is a donkey. That's a horse's head or donkey or something like that. Just as if it was an object. Because we don't know ourselves subjectively. Anyway, our problems are mostly come from the fact that we know only part of ourself.

[25:33]

Those of you who aren't used to sitting this way, I hope it's not too difficult for you. Please, if it gets very painful, please move your legs or leave or whatever is comfortable for you. Do you have any questions, anything you'd like to talk about? I'm not sure about Vincent being so fun. I still feel like Vincent is good somehow. Like, Vincent is okay, but Vincent is somehow the bad guy.

[27:06]

I thought this feeling would go away and it didn't, but it's just painful, but it seems like quite a while. I don't know what to do about it. Do you have any suggestion? For myself or for Vincent? Yeah, for Vincent. For Vincent. Ah, you choose. For Vincent, some suggestion. It seems like the opposite could go well then. Don't think? It doesn't seem like they do.

[28:10]

I think they do. In a dental? Uh-huh. Where? I don't know. Well, anyway, the officers do what is necessary, but wait until you're an officer. If I'm not going to go to prison, what am I going to do? I don't understand. What practice do you support? If it ends, would you get busy? I don't think practice ends for the officers when it gets busy.

[29:17]

It's true that because Zen centers, there aren't enough people to do all the work, so the people who do have to do the work are rather busy. What also happens is the very people who are needed, who are most capable, are the ones who end up doing most of the work. It used to be much worse, you know. It used to be the Zen center had only two or three people who could do the work. And everyone else were new students, mostly struggling with their problems. And a big problem for Zen center is that as soon as you get a little bit free of your problems and can do some work and aren't always upset or insecure or whatever, then you get tons of work piled on you. And it will only be solved when more and more people can share the work, you know.

[30:18]

Zen center is a pretty complicated place. And I, as you, I think maybe I've told you, had many reservations about coming back here, partly because of the size of Zen center. But Suzuki Roshi felt it should continue as it is. So we're trying. It might be better in some ways if it were several small groups. But there's no way to do that at present. Yeah? You said, you know, giving a girl, you know, this stage. Well, in traditional Buddhism, the traditional explanation is there, you know, if you read the sutras, they say something like

[31:43]

when sons and daughters of good family do such and such, that actually those kind of phrases like bearing the right shoulder refer to quite a, there's sort of a compensation of something. And all that means is the same as what Suzuki Roshi said, When students come to Zen center, he has to have students who had lots of preparation before they started practicing Buddhism. And that kind of practice is finding your own way to survive in your culture. And traditionally, they thought that if you didn't, weren't quite an accomplished person, you couldn't start practicing Buddhism. But tantrism and Zen don't feel that, you know, they used to say, if you had, you know, great problems, you could never practice Buddhism.

[32:52]

But tantrism and Zen think that if you have, that people with great problems can also practice Buddhism. So most of, most, partly what I was referring to is that yesterday I talked to San Francisco about several things, but one thing that came up was, we have, Suzuki Roshi said, we have limitless problems because we have limitless desires. But usually, so usually you think, if I get rid of the desires, then I'll be, have no desires. But Buddha nature will be uncovered, something like that. But what we mean by Buddha nature isn't some nature or seed or, it's just what appears each moment. I can't, it's not possible to explain what I mean by Buddha nature.

[33:57]

But many questions then came from the people there about desires, what to do about desires. Well, Zen practice is usually, you know, to enter into desires. Your, you know, your Buddha nature may be, we call it emptiness or we call it Buddha, enlightenment. We can call it evil desires or ignorance. But that kind of practice, most people don't understand because they're involved with, they have some problem and it causes somebody else suffering and they want to get rid of their evil desires. Well, the stage of trying to get rid of your evil desires is that stage, that beginning stage, when you're trying to hit the drum. Do you understand what I mean now? Or is that too complicated? Too complicated. Yeah.

[35:09]

I don't understand what you mean when you don't know yourself sufficiently. What is what you don't know yourself? What you don't know yourself. Well. It's like when I was at Lama Foundation in New Mexico, that it's a commune that's in New Mexico, which has both practice and people living there. And they, I sat with them for a couple of days and they want to know why we sit the way we do.

[36:18]

And it's pretty difficult to explain why we sit the way we do. So the first... Firstly, you know, you can say we sit this way physically, but most of us perceive our physical body only. So I had to say, there are many bodies which sit, Satsang. So, because you don't know all the bodies. But actually there aren't many bodies, there's just this body. But we're only aware of such a small part of it. And we're concerned with how we look and feel and what other people think of us. That's knowing ourselves objectively. When you know yourself subjectively, you don't have any of that kind of consideration. Do you see what I mean now? We think that this posture is some physical... But that's, you know, if you know your body thoroughly, this posture is not rigid at all.

[37:30]

It's the most comfortable and open, relaxed posture. Yeah? I'm not clear on how your practice helps you to understand yourself subjectively. It's a... I understand. It's a... It's interesting to speak here, because some of you don't know much about Buddhism. And you're just visiting. And some of you have practiced quite a while. Most of you are in fact newer students than the students in the city. But you're practicing here at sort of half a monastery now. It's such a... hard to... speak directly to that, because supposedly most people here know that already.

[38:31]

But anyway. There's many ways of saying so, but... We sit this way, because normally we only know ourselves objectively. How we think, what thoughts we have, what kind of feelings we have. But we don't know who we are between thoughts. We don't know who we are if we didn't have those products so far. So the only way, the shortcut anyway, kind of shortcut, is to just sit to... as long as you're taking activity, your activity, you know, if you're running for a bus, you can't solve a calculus problem so easily. You know, what kind of physical posture you take affects you. And whatever you do, you are what you're doing. So, how to find out what you are when you're doing as little as possible,

[39:32]

in a way, you know, something like that. So who are you if you're not thinking? Between thoughts. So, to find out what we are if we're not taking some particular form, we take this posture. But actually, this posture or lying flat on our back are both nearly the same. But if you lie flat on your back, you tend to fall asleep. But this posture, all your organs and body is quite unrestricted. As soon as you bend like this, you squash your stomach. If you squash your stomach, you squash the older part of your brain, which affects your emotions and things like that. Stomach. Stomach. Why is there a precept against drinking?

[40:35]

There's a precept against intoxication. Why do you think? Well, I can experience it both in my life, and I feel like I'm drinking a lot. And I want someone to tell me the reason why. But if you, aren't you telling yourself you shouldn't then? Why don't you have the resolve to do it? I don't feel like it's gotten desperate enough. You've got it. Anyway, that's like you have the idea, thought of enlightenment,

[41:44]

and then you have the vows. So you have, usually if you're practicing, you know what to do. But the problem is doing it. You know, but you just make some resolution and do it, that's all. But if you practice zazen long enough, and you're actually practicing zazen, it becomes rather unpleasant to drink. It's sort of a nuisance, you know. I don't know, it's just sort of a nuisance. But the beginning practice is you don't do anything which alters you. You know, the precept one is do not kill, which means do not kill yourself. Don't do things which make you dead. And the second is do not take what is not given. All of these are based on interdependency. And I guess it's the third, which is often translated do not drink,

[42:49]

but actually it means do not, as Zukiroshi used to translate it, do not sell Buddhism. Do not intoxicate people with Buddhism. But I guess it's most accurate that you could say something like it means do not do anything that alters you, your mind or body, or another's mind or body. So, particularly in zen practice, we have neutral food, not much... not too colorful food, you know. In the first stage of practice, which is form is emptiness, that stage of practice, we're strict with ourselves, so we know what it is to look without getting caught. And so you want to know what you are without adding anything, without adding some movement, without adding thinking,

[43:51]

without adding alcohol or drugs or dope, sex. That's called form is emptiness practice. But zen, for zen, we usually say that if you sit, all the precepts are there. So if you sit, your subjective experience of yourself is such that you wouldn't want to take a drink. You feel so, you know, quite good, actually. So to add something so crude as alcohol... But until you know that, have a sense of that calmness of your mind, then drinking is rather nice. Someone said to me, one of those people in the east said to me, is zazen anything like the first flush of a drink? Maybe it is, I don't know.

[44:59]

Yeah. How do we make decisions from moment to moment, right? Whether to talk, or remain silent, or to go for a walk, or to sit in the cushion, or to read a book, if you get a book, or to go swimming? And just, maybe three things arise almost at once. Yeah, I understand. Well, there really aren't, actually, there aren't choices. There's only one thing that should be done, usually. But it's hard to find out that... But when you... I can say, when you know yourself subjectively,

[46:06]

you don't have problems with making decisions, because you don't think about what to do. The alarm clock rings in the morning, and you just get up. You don't think, should I get up, or should I not get up? Should I go swimming, or shouldn't I go swimming? Should I put up a practice? Yes. That's why we have this kind of... Practice, particularly at Tassajara, though it's difficult during the summer, should be very strict. There should be no missing zazen. No... I don't know what to say, because I feel... You know, I think if you start zazen, you should, for five years, you know, if you're practicing for five years, you shouldn't miss zazen for five years.

[47:07]

That's all. And if the alarm clock rings, you get up, that's all. And at first it's rather difficult, but after a while, when you have that calmness, or when you know yourself subjectively and objectively, whatever you do, you feel comfortable, in any kind of circumstance. So there isn't even any need to do anything anymore, because how can you go anywhere, because you're already everywhere? But there's no way to find out what we mean by that, unless you're strict with yourself. So here we create a situation which isn't very strict, actually, at which, you know, we get up and we practice a certain way. But it takes... Zen practice can be a kind of therapy which clears your mind, you know, makes you feel better. Or it can be actual practice. Actual practice means you have to be

[48:10]

very strict with yourself for... I'm sorry to say, at least probably ten years. Maybe five years. So... But within that strictness you must be relaxed, as in our posture we should be relaxed. So... I think when you're practicing Zen, you know what you should do. Then you should find the resolution to do it. But exactly how to make a decision, you know, there's some process you can actually... depending on the decision, how to bring your whole mind and body into the decision-making process if it's a big decision. But in little things, I mean, if you want to go swimming, go swimming. Do whatever you can do, you know, something simple like you can go swimming or you can go talk with a friend.

[49:11]

You can do that. Do one of them. Don't change your mind. Even if it's a mistake and you're halfway to the swimming pool and you say, I'd rather talk to my friend just to go jump in the pool. That kind of thing, whatever you do, just do it. It's necessary. Then you go talk to your friend and you talk to your friend and you say, boy, is it hot, I should have gone to the pool. Then your life is, you know, no. To do that. And I think, first of all, you have to have a hierarchy of values. And the top has to be practice. But practice includes responsibility to your family and your children. So whatever your responsibilities are,

[50:12]

you have to do them. But, you know, you see, the difficulty with that kind of discussion is I don't know you well enough to know exactly what your situation is. But, or how you understand what I mean. How to explain what I mean to you. But, let me just talk about something I talked about with somebody else the other day. Is, they want Zen Center to become a place where families and children can practice. And that if you have to watch the children, you miss Zazen. And if you, what Zen Center should do is it should change and become a kind of place

[51:14]

which allows residence for people. But this would be sacrificing practice is the main thing. But it's possible to go to a place to have a village or a group of people who practice Buddhism who the main consideration is, main considerations are the community. And if you practice that's good too it helps the community. But mainly you're concerned with how you own the land and who takes care of the houses and how the children are taken care of etc. Now, in your own life you have to try and find some balance for that. But as much as possible if you understand that you can't really lead your life or bring up your child unless there is your larger sense of practice. If you have that larger sense it's manifested in what you do even if it's only taking care of your child. But if your horizon is limited to your child or your family then you can't have that kind of practice.

[52:17]

But if your horizon includes everybody and you practice with that sense you don't even have to do Zazen. Zazen is a good help. I think it's getting late. Okay? Yeah? I was saying that if you don't even practice for example if you feel that you're going to be limited in practicing and restricting then it makes sense that as soon as as soon as you can more and more fastly avoid more and more restrict yourself to that. Okay, when you're quite free of it that fascination is the problem one of the problems. When you're quite free of that then you can try

[53:19]

the next stage of practice in which you practice with form with not restricting yourself. You said that restricting yourself or restricting yourself I mean I don't see that that's the other way I don't see restricting yourself maybe to be to live a life of that's what I'm going to ask you because there's one kind of science practice that is known in the literature maybe you can see that there's any conditions for that that we have now maybe in the actual experience that there was something that was causing that maybe it's just

[54:24]

maybe there wasn't so much that was causing something yeah well later practice becomes zazen becomes just the expression of your the deepest expression of your nature you don't do it for practice like in the usual sense but you do it just because it's the deepest way to express to feel your whole to be your whole being but practice well anyway I'd like to say this

[55:31]

to let you come to a place where don't get too comfortable with the experience that you've gotten yourself because you've had a lot to do and I know you don't get that but I'm glad you're continuing to come to this problematic place well we have to know our own ecology before we can help others we have to know ourselves you know to say again subjectively then the whole world is familiar so

[56:33]

you know it's easy to get caught up in in and maybe if I wasn't here at Zen Center I'd be doing something else but there are many kinds of distractions like that the Vietnam War or ecology if we're going to practice we have to make at some point be strict with ourselves and even something so similar to Buddhism as ecology and so important when you know it may be our disaster if those problems aren't solved still we're strict with ourselves it doesn't mean we're not contributing in some way I mean here is one of the main ecologists in the world Lindbergh was trying to do a great deal wanting to come to Buddhism so he's very interested in having us tell him how he can think more deeply about the problem

[57:33]

@Transcribed_v002L

@Text_v005

@Score_89.21