You are currently logged-out. You can log-in or create an account to see more talks, save favorites, and more. more info

Effortless Equanimity in Zen Practice

AI Suggested Keywords:

The talk discusses the concept of non-discrimination in Zen practice, emphasizing how practitioners should approach zazen (sitting meditation) without distinguishing between good and bad experiences. It is suggested that practitioners exert "right effort" consistently but also recognize times when less effort is required. The relationship between consciousness, concepts, and control is explored, highlighting how one's usual consciousness leads to feeling disconnected and controlled by life events. Emphasis is placed on integrating Zen practice into one's life, using breath and awareness to clarify consciousness and activity. The conclusion touches on concepts of enlightenment, interconnectedness, and the continuous practice of Buddhism beyond rigid labels or experiences.

Referenced Works:

- Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch: Addresses the metaphor of mental clarity through the straw man (Shenshu) and the value of seeing each sediment as a jewel, illuminating the universe.

- Eightfold Path: Specifically “right effort” integrated with non-discrimination to balance effort in practice.

- Poem by the Sixth Patriarch: Contains the line "Who would have thought?" which expresses the realization of one's immutable self-nature creating everything.

Important Discussions:

- Non-Discrimination: Essential attitude for Zen practice, focusing on undifferentiated engagement.

- Right Effort: Integral to the Eightfold Path, advocating balanced exertion in practice.

- Consciousness and Control: How usual consciousness, tied to concepts, limits awareness and connection.

- Sediment in Glass: Symbolizes mental clutter, needing to be settled and seen as valuable.

- Buddha Nature: Difficult to locate but fundamental to practice, suggesting one should have confidence in an expansive nature.

- Interconnectedness: Stressing the profound interconnectedness of all beings and actions, beyond personal karma, to a shared, enlivening practice.

Speakers/Teachings Referred To:

- Shenshu: Referenced for the verse about mental clarity and cleaning the mind.

- Suzuki Roshi: Mentioned regarding personalized guidance on Buddha nature and practicing without rigid conformity.

- Nyogen Senzaki: Known for stressing the importance of practicing with diligence and awareness of one’s actions.

These points frame the practice of Zen as a continuous, integrated experience that transcends attempting to control or label life, emphasizing a shared journey toward enlightenment through practical applications of mindfulness and non-discrimination.

AI Suggested Title: Effortless Equanimity in Zen Practice

AI Vision - Possible Values from Photos:

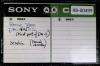

Side: A

Speaker: Baker Roshi

Location: Tassajara

Possible Title: Sesshin

Additional text:

Side: B

Speaker: Baker Roshi

Location: Tassajara

Possible Title: Sesshin First part

Additional text:

@AI-Vision_v003

Everyone always says in sesshins that when the third day is over, you know, the sesshin is... from then on it's easy. I've never found that to be true, actually, and when people say it, it always makes me just wish it were true. But the third and fourth day, some kind of change does occur. Maybe you give up. And the most important overall attitude to have in our practice is non-discrimination, no viewpoints. So, you really shouldn't discriminate, you know, good zazen or bad zazen.

[01:12]

But within that, it's nice to have good zazen. So, if you can manage those two things at once, to not discriminate, and yet make some effort, you know, the eightfold path, you know, includes right effort. And right effort should come under the heading non-discrimination. And sometimes you should make more effort than other times. And I think in a sesshin like this, it's good to try pretty hard all the time, but, you know, it's maybe useful to set aside some particular period.

[02:15]

Maybe you could take one or two periods, the worst two and the easier two, you know, that in the morning when you're a little more awake and your legs are a little better, to try to sit as completely as well as you can for one or two periods. But then also take some period which you know is the one you dread the most, and try to sit completely as well as you can through that period too. But then, just in the next period, don't punish yourself because you're not trying quite as hard. You know, you don't have to try the same hardness all the time. Why do we make any effort at all, if we're all... if this is just one great big being

[03:32]

Well, one reason is that our consciousness, particularly when linked to concepts and to control, doesn't participate, you know, it tends to shut out the world. So you really get caught. And if your consciousness is only that kind of consciousness, you're pushed around by life, you know. You're in the world of too late, it's too late to do anything about, too late to see what's happened, you know. The ball's already gone past you. The sage, you know, so-called, Sukhyoji always said the sage, the so-called sage, you know,

[04:44]

is at the source of his own action. He sees the great stream of events, you know, which is our life. You know, there are... yesterday I talked about the, you know, pre-voice of the ten thousand things, but there are millions of things in this world, and they're all in some kind of concord. And as long as you think life is important, more important than dying, you can't see,

[05:46]

you know. It's interesting, I have a Christmas card that someone sent me once, in fact, a population expert who's a Christian, sort of, but very interested in Buddhism, and always trying to see the similarities in all religions. Anyway, his Christmas card says something like, I don't know, holy hidden being. And a holy hidden being, maybe that's something like... maybe that's a Christian way of expressing something that Buddhists feel too, some immutable, pure self-nature which manifests everything. But then, the next line of the Christmas card is something like, help us, brother love,

[07:04]

or help us to love the world you created, holy hidden being. And then, the last line, something about the word made flesh. At least, from the point of view of that Christmas card, the emphasis is on the world God created. And the creator is almost like, his whole purpose was to create it, and then you can sort of... I don't know what he's doing back there, watching, maybe. But from the point of view of Buddhism, you can't separate the creator and the created. So we say, no creator even, no origination. You can't find beginnings and ends.

[08:04]

You can't emphasize form and forget emptiness. So in form we see emptiness. And the more you can wait, you know, wait for all things to advance and to practice, the more you can wait for others' understanding of you, the more you see thousands of confirmations or concordances or something between everything. You can almost predict the future, because it's just very clear, you know, that the interrelationships

[09:13]

between things are so minute. Free voice touches the smallest thing. Interrelationships between things are so minute that it's very clear, you know, what's happening. And to interfere with it, you know, to try to love it or interfere with it, you know, you might clear a little space for yourself, but you kind of wreak havoc over there. So when you give up thinking one thing's more important than the other, you can begin to see how everything is equally real, equally unreal. And if you get caught by it, you know, you become Gene Dixon or something, and are trying

[10:15]

to figure out what's going to happen, and you give it some kind of reality, as if it, you know, counted. But the more you see this stream that we're in, the more unreal it is, not unreal, but unreal, the more you see it's your own breath, you know, or everyone's breath. Looks like real substantial events, but actually it's everyone's some... you know, at first looks like everyone's karma, or your own karma caught with everyone else's karma.

[11:16]

But then it's, you see, it's more, it's what you really want, what everybody really wants. Hard to see that it's what they really want at first, when you prefer one thing to another, from the point of view of usual conscious mind, but it's what they really want. And then you see that you can't even say it's... I mean, it's emptiness itself. So how to practice in this kind of situation is what practice is, and as soon as you begin

[12:24]

to see that trying to work things out from our usual conscious mind and control things... usually we limit our consciousness to what we can control, you know. And we think of consciousness as that area in which we can remember things and see things and, you know, some... like the realm that's within a flashlight. We can pick, oh, this is that. But consciousness is much wider than that, and when you begin to see that, you can't practice any longer, you can't live any longer such a fruitless kind of existence, which is both dull and simultaneously addicted to stimulation.

[13:27]

So you start to practice Buddhism, and maybe the first thing you do is you try to practice Buddhism to prove it's wrong and you were right, and some of you ask questions in that way. I'll show you Buddhism's wrong. The way I understand my life and the way it's working out must be real, so I'll accept as much of Buddhism as works in my life. So when you ask such... that's a good question to ask, actually. I mean, it takes a while to realize that you can't ask questions to solve your own karma. Anyway, so you ask such a question, but then, you know, coming forward to be Suzuki Roshi's

[14:40]

companion. You ask such a question, but then you look for the answer in words or in something that you can understand, and when the answer is in the situation itself or in just the opposite of what you expect, you reject Buddhism again. So, anyway, you see the limitation of the usual way of thinking. And that somehow you feel out of it, you don't feel connected with your friends, the people you want to be your friends. You don't feel connected with the world.

[15:40]

It seems to go on without you or be horrible or something. And you can't figure out why, but you have some sense that it's the limitation of your own consciousness. So the first step, maybe, is to try to suffuse your consciousness with your breath. So we start to practice zazen. Maybe, at first, our zazen is like maybe a glass of water full of sediment, and you try to let it settle and the sediment settles out, and you see this nice clear mind, but then you don't know what to do with the sediment. That is very much like the Six Patriarchs' Straw Man.

[16:52]

I don't know how to pronounce Chinese, but it's something like Shenshu, I guess, S-H-E-N-H-S-I-U. Anyway, he probably was much better than the Sutra of the Six Patriarchs, written by the Six Patriarchs' disciples, make out, but anyway, his verse is, you know, about wiping the dust from the mirror, and that's like the sediment in the glass. And the Six Patriarchs' poem says that each sediment in the glass is a jewel, maybe, empty and illuminating the whole universe. But first we need some participation with our life.

[18:03]

So you start to practice, and you try to sit as well as you can, at least some periods, and pretty well the rest of the time, I hope. And your thinking becomes more clarified and wider, not really different, just more clear. So your breath, you know, widens your consciousness, but just right thinking in that way is not enough. We also have to have right activity. And concepts, you know, are usually a product of idleness.

[19:09]

As I said yesterday, you know, it's like to have some idea of a good teaching or good teacher or some, this is good or this is bad, it's like an attempt to find a place to rest. There's no place to rest, no, we have to keep traveling, you know, the world is changing. And all you can do is wait for it to change and to travel with it. So in a kind of idleness you try to label everything.

[20:22]

That's the... the world of labels is the world of too late, and you try to get it so you... Oh, this makes sense, you have a label and a label and a label. Maybe it's useful actually to do that for a while, I mean, when there's no labels and you're completely confused, it may be better to get some labels around, figure out. Then you can start to see the labels don't make much sense, but... Maybe so we start out with some labels, Zazen, and sit still and things. But don't be idle, you know, right activity is probably the... It seems to be the last words of most or many Buddhas or teachers, I think Buddha said something like, practice with diligence, some translation, I've seen about ten translations,

[21:24]

all of them a little different. And Nyogen Senzaki, whose ashes are on that first peak up there, some of his ashes, the Suzuki Yoshi admired Nyogen Senzaki very much. He said, don't, see, know your own hands, I think he said, don't put any head above your head, any other heads above your head, which is a rather famous Zen phrase which Suzuki Yoshi has given lectures about too. And then he said, and watch your own feet, or doing, moment after moment. And the Han, you know, out here, we hit the back of it, the characters on the back, it's not always written the same on Hans, but I think usually it says something like, listen

[22:28]

carefully everyone, great is the problem of life and death. Know forever, quick, quick, awake, awake, each one, don't waste your life. Suzuki Yoshi translated it, don't goof off. So, what does right activity mean, you know? Right effort in your practice and in your life. Somehow your life, your practice has to suffuse your life with light and breath too. So maybe at first we need some wisdom to organize our life so that we can practice, and that

[23:38]

gives us some experience, some ability to find some calmness and begin to see our relationships with each other and our relationships to ourself. But you also have to find some way to practice with all things. And you can say, you know, you can't treat your life like that mess I left behind, but you're never going to look at it again. But you also don't have to go out and look for it again. If you're practicing, it'll come back, don't worry. You know, practicing with all things, I say, but Buddha supposedly, when he was enlightened,

[24:51]

what we now call December 8th, with a morning star, said, I am enlightened with all things. Not I have enlightened, I'm enlightened with all things. If all things are enlightened, I'm enlightened. So, you can't say he's enlightened. For convenience, you know, if it helps people to think, oh, so-and-so's enlightened, then you can think so-and-so's enlightened. But if you're enlightened, it has no importance, you know, like being alive or being dead. It has no importance, so you can't say enlightened or not enlightened. And if enlightenment is any particular point of view, it's not enlightenment.

[25:59]

So actually, Buddha is one being with two sides, you know. One side is Bodhisattva and one side is Buddha. And the Buddha is enlightened with all things and the Bodhisattva waits for all things to be enlightened. One is from the point of view of nirvana and one is from the point of view of samsara. So, you know, a kind of disservice has been done. And a lot of the Zen literature, by emphasizing enlightenment, because it gets you pretty

[27:04]

involved in looking for some experience. And recently, some Zen teachers have emphasized it more than the traditional schools, Rinzai and Soto. And if you know Rinzai school, they emphasize it more than Soto school, but they have a... much of their teaching is how to get free of the emphasis. And Soto just is a little different. Soto's way is more, the student comes and says, �Oh, I've had this wonderful experience!� And the teacher says, �Oh...� or doesn't notice something. But the student should do that, you know.

[28:08]

If the student has a wonderful experience, the student should do that. And the teacher should say, �Oh...� because... because if it's a wonderful experience, it's visible, you know, everywhere. And we don't have to emphasize some particular moment. If you do that, there's some danger in that. Our practice only has meaning if it's moment after moment. So when you see it's moment after moment, then in each moment, the minute communications between each one of us realize our nature. So how to illuminate our life?

[29:50]

Maybe, first, we... One way to say is to say, we have dinner with Dogen and Eicho and Hogen, Basso, and yourself. You know, Buddha was a great teacher because he taught his own way. He didn't have some big rule book of immutable truth that he discovered, you know, and looked up and conformed to. He from his own experience, his own nature, you know, taught Buddhism. So you're Buddha, or you're Eicho, or you're you.

[31:04]

So how can you find what satisfies you? Why not? Why can't you? If you can, there's no problem about how to practice Buddhism. When you sit this Sesshin, you'll be sitting with everyone and with all your teachers. When you enter into the stream like this, of the teaching and this actual life of 10,000

[32:16]

things, we say, then you find your karma isn't your hindrance, but just the way you swim. And the more you see how unreal, not unreal, I don't know, beyond being real the stream is, then you can float or get on Buddha's raft or whatever you want. So how do we participate in this stream without, you know, even Buddha's clothes or our teacher's clothes

[33:28]

or this teaching's clothes, not even with your mind and body? Okay? If you can practice with your life and with the things of your life, waiting for them and suffusing them with your breath, you know, maybe having the same attitude toward the things of your life as you do toward your breath, then everything will, everything that your life is will begin to be clear to you and will come together.

[34:31]

And even though you do exactly the same things, maybe it's too much to say, but we say, you enlighten everybody you come in contact with, and that mess you left behind will be no longer the same. But you need to have more confidence in your, I don't know, true nature, the original nature, you know? After the Sixth Patriarch's poem was accepted by the Fifth Patriarch, he then composed another

[35:38]

poem which has a line in it, something like, Who would have thought? I think that's a wonderful way to start. Who would have thought? Who would have thought that this immutable self-nature, original nature of all things, creates everything? And you can see yourself in this stream just as real as anything else, maybe, creating everything on each moment, with each breath. You know, you lack some confidence, and if I say Buddha nature, that's confusing. I remember I was practicing a couple of years and finally I… This whole business of Buddha nature bothered me, you know?

[36:39]

Where was it? And the idea of soul wasn't so good. I didn't like Christianity because of the idea of soul, so I cornered Suzuki Roshi once on the steps of Sokoji, and I said something about, what is this business about Buddha nature? Where is it? I can't locate mine. And he, I don't know, he looked at me and he said something like, it's a difficult problem or it takes a long time. So we can't say Buddha nature is something you can locate, but for the purpose of practice

[37:41]

we can say it's something you should have confidence in. You know, we say our consciousness, you know, big mind or something is realizable only when we realize it's beyond realization. But anyway, you can have some confidence. Every one of you, you know, can practice Buddhism. Every one of you can be Buddha or be Suzuki Roshi's companion. You know, nothing would make Suzuki Roshi happier than if all of you were his companion. Nothing would make me feel better than if I could share this robe with you.

[38:46]

And you just need some confidence, not confidence in you, but confidence in some nature bigger than you. And so be awake to yourself. Don't leave some corner unlooked at. Only from the realm of being does it look like something's wrong. You know, this is wrong. That's something wrong somewhere. From the realm of being and non-being, there's just a great stream. And when it's form, it has an enormous amount of form. So much form you can't believe it. And the more detail you see, how immense the form is, this stream is.

[40:06]

That takes care of Tassajara and us and how each of us, you know, has secrets of each other sort of locked up in us. Sometimes we have... our karma is so locked up with another person completely and we barely know the other person. You don't... you have some surface feeling, oh, I like that person or I don't like that person. If that person says that again, I'm not going to speak to them. And you don't see you're completely, you know, forever maybe going together. But the more you see that, the more unreal the whole thing is. It's just a wonderful kind of flow. It's very hard not to hinder it, though. Very hard not to try to interfere.

[41:10]

As in that story yesterday, he said, you do not hear it, but do not hinder that which hears it. And that's maybe the hardest part in our practice, to not hinder that which hears it. Do you have some questions? Yeah. See how immense... see how immense the form of history is. We move through a view of, say, practice of non-discrimination. Yeah. I look at the crystals of civilization, which is all discrimination. That's what I can see. You see how immense the stream is, yet you can't see, you can't locate your information.

[42:23]

You talk to someone, understand them. I can't see a thing. I'm in the dark. I keep waves in my head. Because all I can see is discrimination. Yeah. In fact, it's non-discrimination. All I can see is discrimination. Now, I'm in the dark too. He said yesterday that same story. He said, have you heard inanimate objects? And he said, no. He said, then how can you know what you're talking about? And he said, I can't speak.

[43:28]

If you don't speak, you know, on this point Suzuki Yoshi was talking about, that we still speak, that we still discriminate. Otherwise, you just speak to sages. You know, you don't say anything. So we have to say something. So you have to do just what you're doing. I think, practically speaking, having some sense that you do, is more out of the dark than you think. But our mind, you know, refuses to see that we're already enlightened. Our mind refuses to see, you know,

[44:31]

when we look for light, we look for, you know, Con Edison or PG&E. It doesn't work that way. Yeah. What's wrong with the sediment? Yeah. Yeah, we're all at the bottom of the glass, you know, talking to ourselves, you know. So we have a sashin and shake the glass.

[45:39]

It's wonderful. I don't know what to say. You know, it's right before you, but you can't see it. I'm sorry.

[45:58]

@Transcribed_v002L

@Text_v005

@Score_91.94